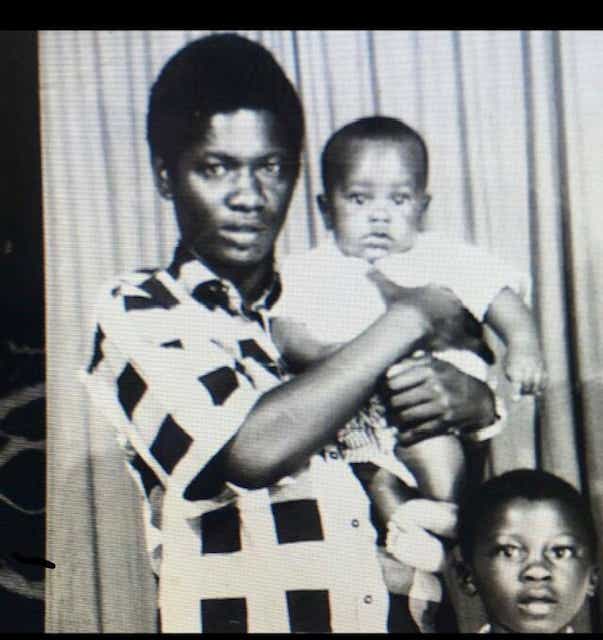

When Betina Ngwaru gave birth to a healthy baby, she and her husband Isaiah were overjoyed. They believed their child, Tatenda, was male, so Tatenda was raised as a boy in the family’s hometown of Gutu, Zimbabwe.

As the years passed, the child that Betina and Isaiah were raising as a son began to express that she was, in fact, a girl. Betina remembers Tatenda begging to wear a dress to school, rather than the shorts and shirt that made up the school uniform for boys. Tatenda explains: “I grew up in a society where women behave a certain way and men behave a certain way and there's no gray area. As soon as I knew how to differentiate genders, I knew I was a girl. It was instinct. When I started school, people would laugh at me because I walked like a girl. And I thought, how am I supposed to walk? I am a girl.” Tatenda’s parents encouraged her to hide her femininity and try to fit in as a boy.

It wasn’t until she was in the 6th grade, when Tatenda had surgery for a hernia, that doctors found an ovary. Later, Tatenda began menstruating. “It was like a bomb being dropped in our life,” says Isaiah.

Tatenda Ngwaru, now 33, is one of over one hundred million intersex people living in the world. The term intersex is used for any individual born with sex characteristics, including chromosome patterns or genitals, that do not fit typical binary notions of male or female. The term is often confused with transgender, which is used for people whose gender is different from the sex they were assigned at birth. The difference is anatomical — intersex individuals are born with sex characteristics that don’t fall neatly under society’s umbrellas of male or female, while transgender individuals are born into bodies that generally do not fit the gender with which they identify.

Tatenda feels lucky that her parents didn’t have the money to take her to a doctor who might have removed some of her female anatomy. “They would have taken away what’s mine,” she says. “They would have robbed me of that choice. I would tell the parents of any intersex child to wait until that child is old enough to speak for themselves to tell you who they are. There was a time when my parents really discouraged me from being who I am, and that weighs on them so heavily now.”

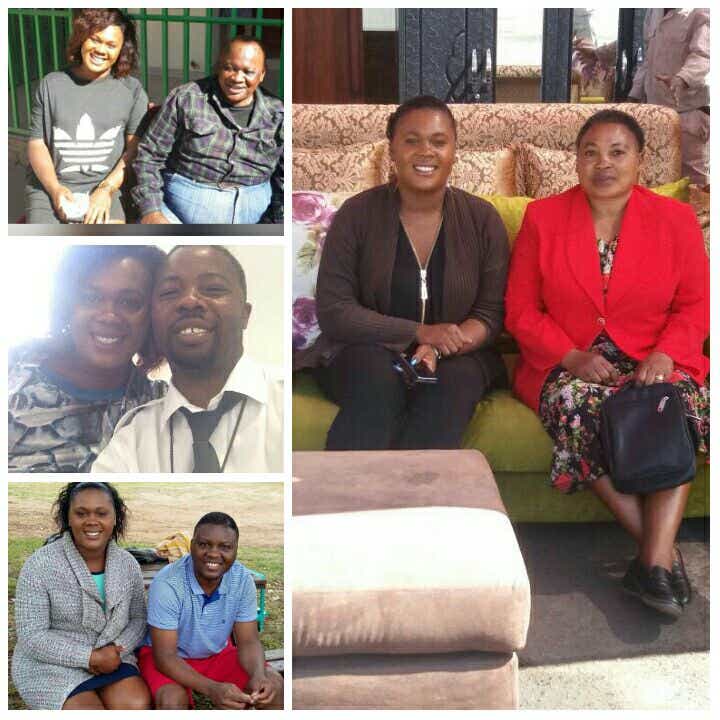

It wasn’t until, as a teenager, Tatenda traveled on her own to South Africa to see a doctor and find out what was happening to her body that her parents realized their error. “After they read documents from a doctor that explained who I am, things gradually started getting better,” she says. “I hadn’t spoken to my parents in a year, and they asked me to come home. They said, ‘You are our daughter. We love you. We accept you. And we're sorry for how we dealt with this before.’ The universe slowly started being kind to me, and it gave me back my family.”

In Zimbabwe, members of the LGBTQIA community face limited rights and legal challenges, and being queer is considered highly taboo. Violence against queer people is extremely common, and the LGBTQIA population has high rates of suicide. As Tatenda got older and became active in the LGBTQIA rights movement in Zimbabwe, the threat of violence loomed constantly. She started a nonprofit called True Identity to promote intersex rights, the first organization of its kind in Zimbabwe — a bold move, considering that anything deemed to be homosexual is considered a criminal act there. Tatenda largely ran the organization in secret, but after a public protest, her office was raided: “I think they wanted to find names of the people I was working with so they could kill all of us.”

One night, Tatenda was targeted and attacked while walking outside. Although she was hurt, she didn’t feel safe seeking help. Tatenda explains, “The hospitals have this rule that if you've been attacked, they won’t treat you unless you have a police report. I couldn't file a police report because I couldn’t tell them I had been doing LGBTQ+ work.” The last straw for Tatenda was when a group of people showed up at her house and told her father, “If you don’t get that freak out of here, we’re going to burn down your house.”

When Tatenda realized that she was no longer safe in Zimbabwe, she moved to the United States. She was only 20 years old. “My family was robbed of me in an instant,” says Tatenda. “The life that I had built was taken away from me. My freedom, my home, all the love that I had ever known, was taken from me. I came here and had to start from scratch,” she recalls. “My father is the love of my life, and the fact that I couldn’t see him made me cry every day. But I decided that if I had to make all of these sacrifices, that I was going to succeed in living my life as myself, and to be a voice for intersex people. That gave me hope.”

At this point, all Tatenda wants is to help raise awareness about intersex people. She recently starred in a short documentary, called She’s Not a Boy, which aims to show viewers the unique hurdles that intersex people face. She also runs her own website on intersex visibility and shares her experience with publications like Vogue. But Tatenda feels like she hasn’t scratched the surface when it comes to educating the public about the intersex experience: “Even within the LGBTQ community, a lot of people don’t know what intersex means. I sometimes feel like the ‘I’ in LGBTQIA stands for invisibility. We don’t have a platform in the community. How can we expect kindness from outside the LGBTQ+ community when we don’t express kindness to one another?”

That’s a big part of the reason why Tatenda wants to tell her story. “The trans community has gotten a lot of attention over the past few years, and that’s wonderful. I just want intersex people to have a seat at the table, too.”