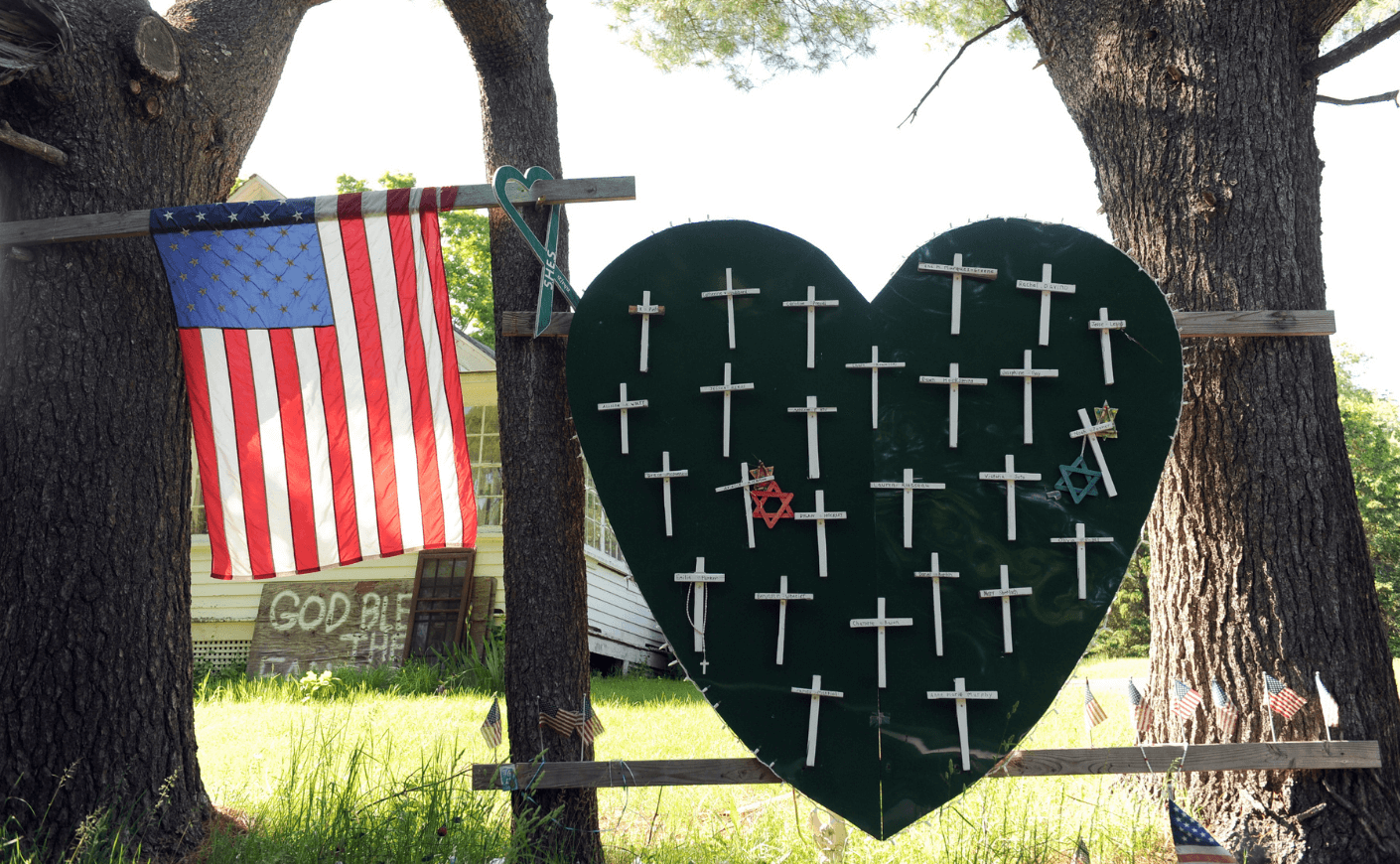

As a feature writer for the New York Times, Elizabeth Williamson is used to being gripped by a breaking story. But what happened on December 14, 2012, stuck with her for longer than she expected. The shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School that day in Newtown, CT, claimed the lives of 20 children between the ages of six and seven, as well as that of 6 school staffers (among others). Williamson watched in horror along with the rest of the country as news reports streamed in, and mourned the loss of so many young lives. What came next, though, was almost equally shocking.

Conspiracy theorists seized on the event as a hoax, an attempt to revoke Americans' access to guns via child "crisis actors." In some cases, those behind the conspiracies bombarded the families of the victims, demanding "proof" that their children had been killed — or ever existed at all. When the parents of some victims filed suit against reactionary radio host Alex Jones in 2018, for spreading a campaign of misinformation about the shooting, Williamson needed to know more. The results of her investigation is the new book, Sandy Hook: An American Tragedy and the Battle for Truth. It's an account of a catastrophic event, and the dangerous, culture-altering ramifications it had on American society. We asked Williamson what everyone should know about Sandy Hook, what it was like to talk to the parents of victims, and how we can stop terrifying lies before they take hold.

What do you personally remember about the day that Sandy Hook happened?

Just like many people, I remember the trickle of information that came out in news reports, and holding my breath as I watched the facts become clearer. I was absolutely devastated by the toll, and the ages of the children who were killed. My youngest son was just a little bit older than those children. For a lot of parents, particularly parents with children that age, it was a doubly devastating blow.

At what point did you realize that this was a topic that you needed to tackle in book form?

It was when the parents of the victims filed the lawsuits against Alex Jones. There were two parents who kind of led the way: Lenny Posner, the father of the youngest Sandy Hook victim Noah Posner, and Noah's mom Veronique Del Rosa. At the same time, Neil Helan, the father of victim Jesse Lewis, also filed a defamation suit in Texas. So I started to look into these cases and realized that for years, these families had been dealing with people who denied that this event ever happened. Not only that — they accused the parents of being actors in a hoax.

Sandy Hook was the first mass shooting to create these viral online claims — that it’d never happened, or that it was a pretext for confiscating Americans' firearms, that the families of the victims were complicit. After that, with every mass shooting, Coronavirus, the 2020 election, and the attack on the Capitol, you could see the same actors, the same ancient tropes they were playing on, and the same delivery method, which was social media.

This book is about the aftermath of the event, as these families were reeling. What did it look like in Newtown? What were the other issues they were dealing with? And how did they grapple with them while people were wandering into the town, trying to prove that the shooting never happened?

I wanted to bring the reader into what it was like when these conspiracy theorists first started to surface, and how the families reacted. The majority of the parents thought, These are crazy people — ignore them, we have enough on our plates. But one parent, Lenny Posner, could see that this wasn’t a one-off situation, because it ignited a heated debate over gun policy. He could see that more of these myths would spring up and they'd spread further. So he took [misinformation] on as a personal cause. And he was absolutely right. January 6th taught us that.

What are you referring to when you talk about those “ancient tropes”?

There’s a close relationship between Sandy Hook and Pizzagate, for example. One claim, that's now an underpinning claim of QAnon, is that people are trafficking in children, abusing and slaughtering children. In that case, they claimed it was happening in the basement of a Washington DC, pizzeria — which by the way, doesn't even have a basement. Their claim was based on the ancient blood libel trope, in which people are complicit in the murder or ritual slaughter of children. The other trope is, of course, that a global cabal of bankers and industrialists controls everything and they’ve been turning all of us to their will.

The victimization of children is an overriding theme here, but the iteration in the case of Sandy Hook is that the children were being used as pawns. One conspiracy theorist insisted that one of the children killed at Sandy Hook was actually another living child in town. This was a child who had fled the school and survived, who was traumatized. And this man released the family's personal information in this insane quest to prove that this living child was actually posing as someone else.

One of the fascinating things I learned was that some of the people who believed in the Sandy Hook hoax were actually parents who had children that age. Some were moms who just couldn't accept that this would happen to six-year-old children. One of the moms I profile in the book logged onto Facebook and found a group called Sandy Hook Hoax. She was like, "I'm here for whoever can convince me that this really didn't happen," because it was too horrible for her to account for it.

Was there an interview that especially impactful for you, emotionally?

They all were really moving, and I can't emphasize enough how grateful I am to the parents for their trust, for sharing their stories with me. There was a photo of Noah where he's wearing a faded brown corduroy bomber jacket with a fleece lining. He loved it. And after Noah was killed, that jacket had gone missing, so the family begged a state trooper to help them find it. It was at the school, on a hook where Noah had hung it. I went to visit Noah Posner's mom Veronique, in Florida, and she brought it out. It had almost a human presence — it was so comforting for her to have it.

Veronique had a lot to say about moving through life having experienced this loss. After the shooting, a team had come to work with the parents and provide counseling, and one woman on the team was from Sub-Saharan Africa. She told Veronique, "In our culture, children choose their parents, and Noah chose you." She also said that when a child dies, the mother spends some time in a place where you’re not really living, but not really dead. She said, "You can go either way, but you have two living children who chose you as their parent, too." And Veronique knew she would continue.

If this event wasn’t enough to impact gun-control laws, do you think there’s any possibility that they could be altered in the future?

I deliberately don’t wade into the gun policy debate in this book. I cover it only in so far as it impacted the families. I feel like introducing the gun policy debate in this book serves the hoaxers. Because if the book equated guns with the conspiracy theories, that fuels the falsehood that this event was all in service of gun control.

One review of your book called it “the definitive account of this dark chapter of American history.” But I found myself balking at that phrase, because it doesn’t feel as if that chapter is over. It feels very much like we're still in a golden age of misinformation and politicization of tragedy.

Yeah, it’s a chapter in a book that's not ended. Lenny Posner has made tremendous strides in getting this content taken down from the internet and social media platforms. But it's like Whac-a-Mole: You beat back one false theory and another one springs up in its place.

In the book's final chapters, I dig into what some research shows about effective ways to try and counter misinformation. In one study, a psychologist argues that once people embrace a conspiracy theory, it’s less about politics than it is about mindset. There's a narcissistic element, too: You’re the possessor of privileged information that no one else knows. There's a group-identity thing that the most hardcore Sandy Hook conspiracists have, a sense that life hasn't really lived up to their expectations. I've looked at transcripts of their chats — they're constantly building each other up and sort of cementing an identity for themselves. So the research shows that it's a hard struggle to try and disabuse someone of conspiracy theory because it’s a mindset, a personality trait. But if you can inoculate them up front, you have a greater chance of defeating the spread of this stuff.

Congress is starting to get the big platforms like Facebook and Twitter to take [conspiracy theories] down and to act on the spread of falsehoods. There’s progress being made on YouTube as well. And at the same time, I think Americans are becoming much more aware. Young people are so internet savvy, they're much more skeptical about what they see as inauthentic content. They don't just say, “If it's on the internet, it must be true.” And I think they're gonna be the saviors of all of us.

What do you hope readers ultimately take away from this book?

The biggest message is — which was Lenny Posner’s message from the beginning — that if these deluded people and profiteers like Alex Jones can come for people who’ve lost their children in a mass shooting, they're coming for all of us.

This is a difficult topic, particularly for parents with kids, but it's so important to understand it. And to see the unbroken line between what happened to these families and what we're all enduring today — the same misinformation that brought rioters to the Capitol. I think the greatest service we could do for these families is to not look away from the horror of what happened to them, and understand what they've done to fight the aftermath of this event. And that's for the benefit of all of us. I'm just so honored just to tell their story.