I loved Tom Wolfe, and when I heard there was a new documentary about the legendary journalist turned non-fiction author turned novelist, I was keen to see it. Radical Wolfe is both a profile of Wolfe and a window into the unique journalistic approach he became famous and, in some cases, infamous for. I caught up with the director, Richard Dewey, to dish about the never-sheepish man in Wolfe’s clothing.

Katie Couric: What made you want to do a documentary about Tom Wolfe?

Richard Dewey: I wanted to write a valentine to a lost era of journalism and writing. It feels like we’re so far away from having writers like Tom Wolfe in our culture, that I wanted to remind audiences of what’s possible and what has been lost.

Michael Lewis provides much of the foundational narration for the film. What was it about his Vanity Fair piece that made it so definitive?

Michael identified Tom’s time at Yale as a turning point in his life. It was the first time Tom had left his southern bubble and the experience shaped his worldview. While most analysis focuses on Tom’s inimitable voice and style, Michael really underscored the idea that it was Tom’s upbringing and worldview that really separated him from other writers in his choice of subjects and how he covered them.

Tom Wolfe seemed to redefine journalism — how did he change the profession in a way that still has resonance today?

There are parts of Tom’s writing and that of the New Journalism movement that are still felt. Tom borrowed techniques from the fiction writer’s toolkit such as scene-by-scene construction, extensive use of dialogue, and point-of-view narration. These seem natural today, but in the 1960s they represented a significant break from journalistic tradition. On the other hand, the type of deep immersive reporting into micro-cultures that Tom did has been on the wane with the decline of print media, which no longer has the budget to support the extensive research that Tom and his contemporaries were able to do.

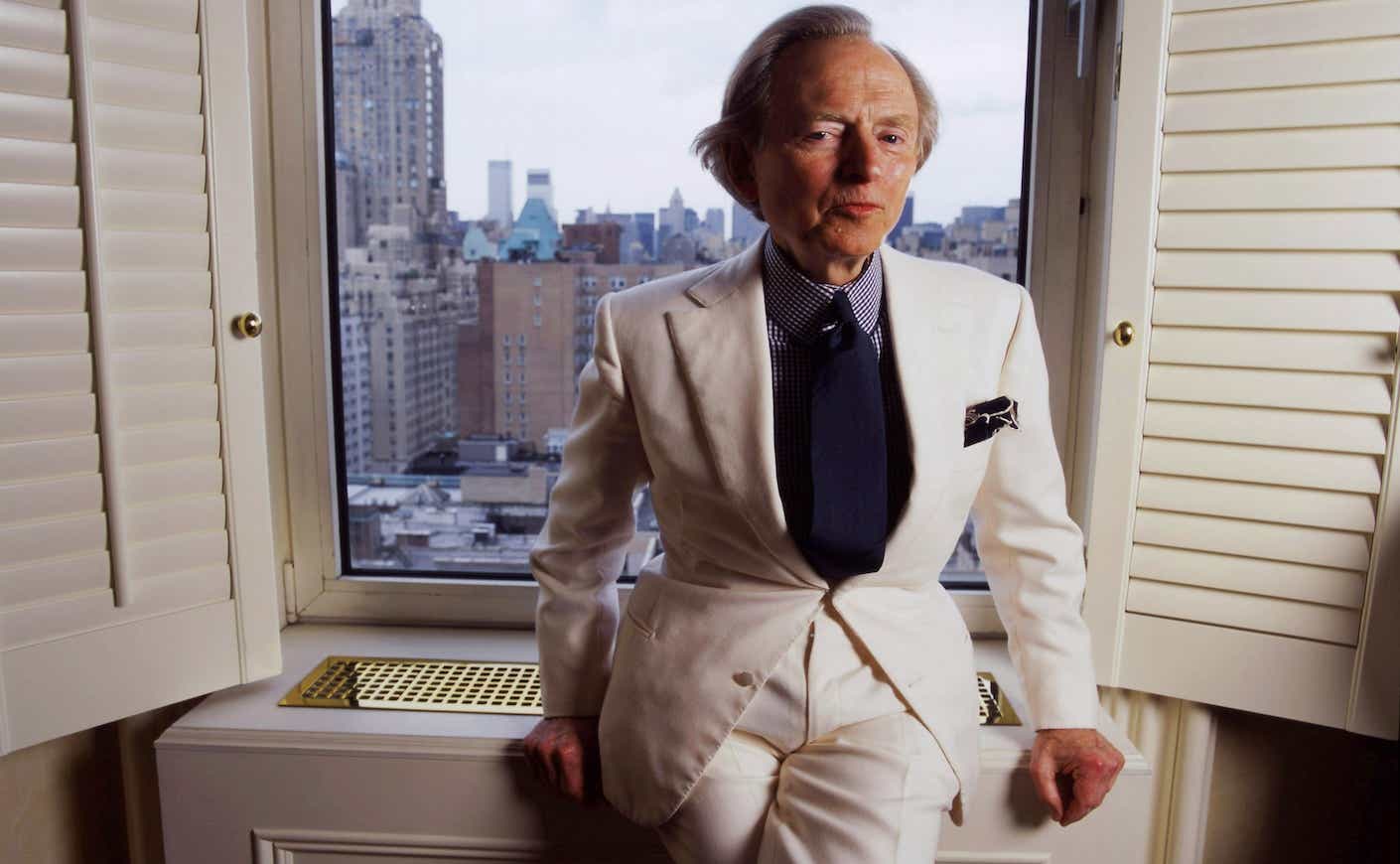

In many ways, he was a fish out of water. A transplanted Virginian in New York City. Michael Lewis describes his white suit as a “suit of armor.” Do you think that’s the case?

Yes, in meeting a lot of Tom’s friends and family, one thing that really came through was the extent to which he was a mild-mannered, reserved person in private. The white suit helped him bridge the disconnect between how people perceived him and their expectations of him and his true self.

The story of how he got into a Leonard Bernstein party and then skewered Bernstein and other rich Manhattanites for raising money for the black panthers was priceless. Did he go too far?

That’s a question that’s still debated today and likely will be for a long time. I tried to present all sides in the film. Jamie Bernstein gives her take, and Jamal Joseph, one of the Black Panthers they were raising money for that night, gives his view. I also incorporate the views of editors and writers who were not involved in the story but reflect on its impact. And of course, Tom offers his thinking as well. Ultimately it’s up to the audience to decide if Tom went too far.

I loved hearing from his daughter. It seems he kept his personal life so separate from his professional one. Can you tell us about that?

There were really two sides to him and my sense is that keeping that division of a public self and private self was important to him because they were very different. It was also about expectations for writers in that era. Hunter Thompson was a friend and contemporary of Tom’s, but it’s been suggested many times that he might have blurred the line between his characters, namely Raoul Duke, and his personal life a little too much. Tom was fortunate in that his personal life was very happy and balanced, which was atypical of many writers from his generation. So maybe the separation really helped him.

He seemed to lose his edge later in his career. Was he disappointed his last books weren’t critical successes?

In the film, Christopher Buckley rightly observes that it’s impossible to keep churning out masterpiece after masterpiece. It seems that culture played a role in the rise of the internet and fewer people reading big long books. But the later novels, while not as critically acclaimed at the time of release, have aged well in terms of identifying underlying problems in American society that later became flashpoints.

A Man in Full is being made into a series. What would he think of that?

Tom didn’t really focus too much on adaptations of his work; once he sold the book, he was pretty clear-eyed that it was out of his hands. Some adaptations, such as The Right Stuff, turned out great and others, like The Bonfire of the Vanities, were noted failures. I think he would have been happy that his work would be introduced to new audiences, but if he were still alive he’d likely be fairly distant from the production of A Man in Full.

As a white male, given greater sensitivities about race and gender, do you think he could have written the things he wrote today?

I think it’s difficult to judge creative works outside the context in which they were created. With The Bonfire of the Vanities, Tom admits in an interview that it’s a book without a hero. And there’s another line where someone says that no one is spared in The Bonfire of the Vanities. It’s probably the case that he couldn’t have written the same pieces for the same publications in the same way today. But I’m not sure I have a good answer as to how the writing would be different or how Tom might see characters and events through a different lens.

What did you personally learn about Tom Wolfe?

I learned how difficult writing was for him. When I read a book or article by Tom Wolfe, I just assumed that voice just naturally flowed from him. But I learned that he had the same difficulties and insecurities that almost all writers experience. In the film, he described the process as agony and he really suffered for his writing.

Ultimately, what was his lasting contribution to journalism and literature?

On a technical level, he’s widely credited with pioneering the first-person style that almost all magazine profiles assume today. You can draw a line between the time that Tom Wolfe and the other new journalists appeared and after they started publishing. On a cultural level, he really reshaped the narrative of key events, people, and even the thematic ideas of what entire decades meant.

Radical Wolfe will be available nationwide on Apple and Amazon on Oct 30.