American photojournalist Lynsey Addario has been present at some of the most tragic humanitarian crises in recent human history: flooding in South Sudan, political unrest in Libya, Russia's full-scale attack on Ukraine, and the Iraq War. It can be a deeply dangerous job — she was kidnapped in Libya, in fact — but the results of her far-flung shoots are also deeply moving and powerful, creating images that connect the viewer to a truth they might not want to face. (She's also the author of two books: the photo-heavy collection Of Love & War, and a memoir called It's What I Do.) And she's absolutely one of my personal heroes.

Addario's latest project is a far-reaching one: From September 2nd to October 29th, NYC's SVA Chelsea Gallery will offer a "mid-career retrospective" exhibition of her photography from the past 20-plus years. It's an astounding body of work, one that has to be seen to be believed. I asked her about the toll that witnessing tragedy up-close takes, how her son feels about her work, and what she hopes that the viewers take away from her jaw-dropping images.

Katie Couric: Please tell us about this amazing exhibition.

The exhibition is a retrospective of the past 23 years of my work as a photojournalist, curated by Maya Benton and Perri Hofmann. The exhibition will walk through my career chronologically, but also display issues I’ve covered consistently throughout my career, like refugees and the displaced, women’s issues, maternal health, and violence against women. We're exhibiting mostly framed prints, some vinyls, some cases with ephemera — from a flak jacket to correspondence with editors, to old cameras.

How did you get interested in photography?

I was originally introduced to photography by a sort of accident: My father had a client — he's a hairdresser — who gave him an old Nikon, and he gave it to me. I was around 12 year old, and almost instantly became obsessed with photography. I photographed as a hobby throughout middle school and high school, surrounded by people like my sister, Lisa, who photographed and assisted photographers, and a family friend who taught me how to develop and print in the darkroom. I spent many evenings and weekends in the dark room in high school.

You've covered so many conflicts around the world — natural and manmade disasters. Why do you think you’re so drawn to that kind of work?

It’s hard to say. I guess in war and all the various types of crises, the frivolousness of life is stripped away, and only the essentials matter. One witnesses what really matters in life and also the true nature of people — what divides and connects us despite geographic and cultural differences. I also just very simply believe in the power of good journalism to document and hold leaders and politicians and decision-makers accountable to their actions and decisions, as war reveals the often horrible and unjust consequences of a nation’s quest for land, power, and money.

Do you remember a moment when you were overcome by the emotion of the moment and it was especially hard to be a detached observer?

This pretty much happens to me at one point during each assignment. A moment where I'm shooting and looking through the viewfinder of my camera, and if I pause for a moment, and put myself in the shoes of the person I am photographing — and allow all the sadness and trauma I have witnessed over the course of the days and weeks (and years) leading up to that particular moment — I usually break down and have to step away for a few minutes. I can think of specific times in pretty much every war, every women’s story, every humanitarian crisis where I get overwhelmed with emotion. But I’m OK with that. I witness horrific and beautiful things, and I'm human. I allow myself to feel and empathize.

This question may be gendered, but how does your son Lukas, who's 11, feel about your work? And do you worry sometimes that your work is just too dangerous? And do you feel like men are never asked this question?

Ha. Men are never asked this question. I remember when Lukas was six months old, it was about a year after I had been kidnapped in Libya, and the late journalist Christopher Dickey asked me on stage if I was going to continue doing this work. And I was just sort of dumbfounded, because I know men who've missed the birth of their children because they were covering a war, and others who've left their wives for months on end with the kids to cover conflicts, and no one ever asks them if they consider quitting their jobs.

Anyway — I worry all the time that my work is too dangerous. I obviously want to be around to watch my children grow up, and to be there for them. I've definitely become more cautious with the amount of risk I take, and I believe my combat photographs have suffered because of this. But the aspects of war I've always found most compelling anyway are the toll that wars take on civilians — on women, children, and non-combatants in general. It's just impossible to do this type of work without risk, though, and even if I try to stay back from more frontline positions in any given conflict, there's always an unpredictability in war. Lukas is 10, and while I'm always open to answering any questions he poses to me about my work and the stories I cover, he has developed very strong protective mechanisms, where he doesn’t ask me very much. I imagine that'll change over time.

How did you select the photos for this exhibition?

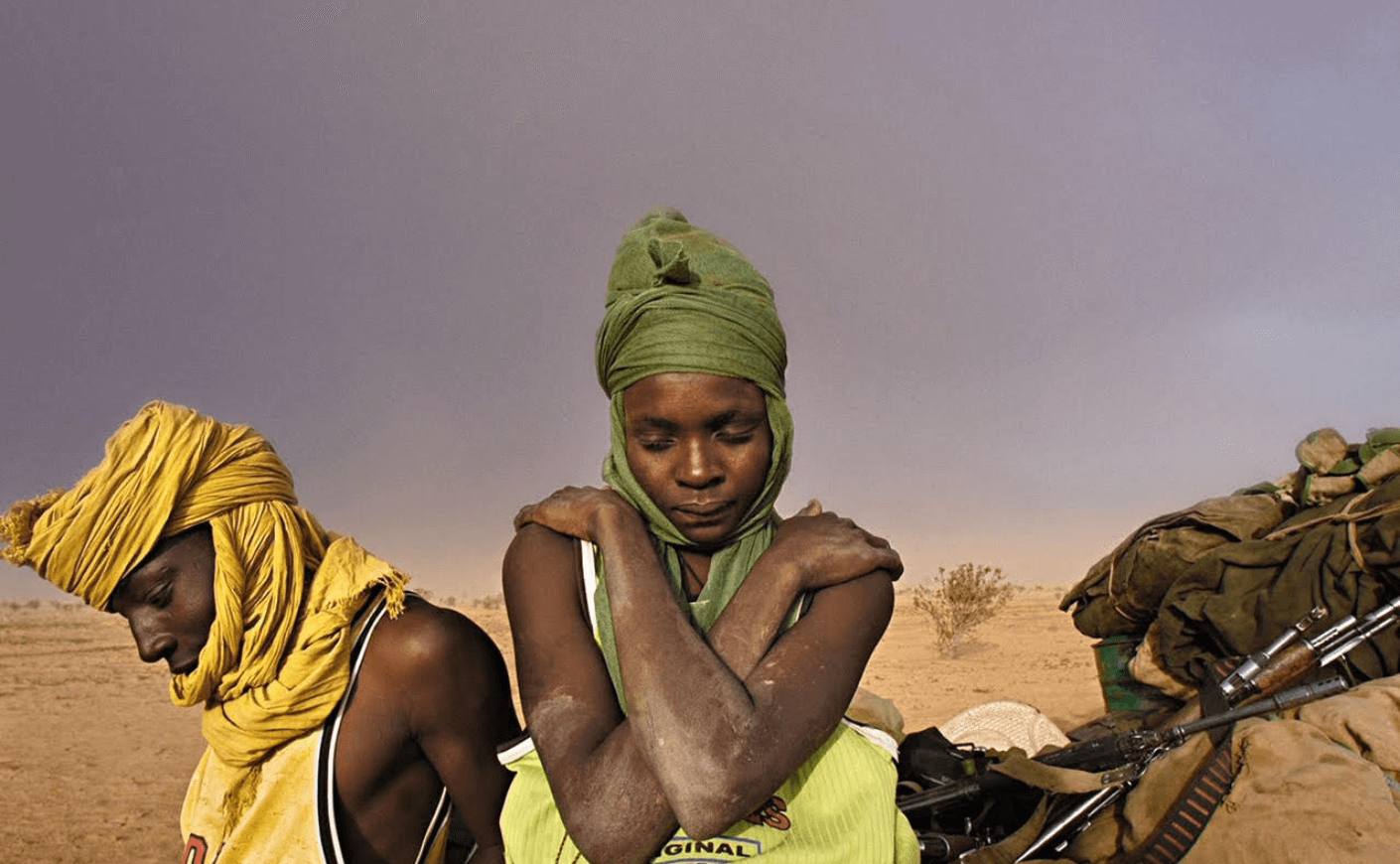

It was an extremely difficult selection process, because I've been shooting consistently for so many years, and my body of work is pretty extensive. The exhibition is for the School of Visual Arts Masters Series award, so it's a true retrospective of my career, and my process: How I got to where I am, both chronologically, and the themes that I've covered repeatedly, from my first-ever series on trans sex workers in the meatpacking district in New York in 1999 for the Associated Press, to Afghanistan under the Taliban 22 years ago to the wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, Darfur, the Democratic Republic of Congo, to maternal mortality and violence against women in Afghanistan, the United States, and the DRC. There are both single images and stories I've reverted to as almost reference points over the years, and so those are included, and then there are some images that the curators — Maya Benton and Perri Hofmann — felt strongly about that are in the exhibit.

Do you have a favorite photograph from your years as a photojournalist?

I don’t really. I tend to be sort of tortured by my work, and never think it's good enough or powerful enough. But there are images as I mentioned before, that I often revert back to, and that are sort of markers in my career.

Your photos are proof of the phrase, “A picture is worth a thousand words.” What do you try to convey in your photos? So many of them are truly haunting.

With most, if not all, of the photographs I take, I'm trying to say something — to tell a story in an evocative way. If a photograph has beautiful like and compelling composition, the viewer is more likely to ask questions, and to pay attention.