Last week, I was watching John Mulaney’s Baby J special on Netflix, where he delves into his drug addiction, intervention, and subsequent trip to rehab. He tells a story about visiting a disreputable doctor who, Mulaney says, never gave out his last name and ended each visit by telling him to take his shirt off so he could administer a flu shot. I was laughing, but then a thought occurred to me that took me out of the experience: Did this really happen the way John describes or is he exaggerating for effect?

But I tried to push it away by reminding myself this was stand-up comedy, not a memoir (though memoirists also take liberties when recalling conversations or interactions), and dwelling on whether the interaction actually happened exactly as described took the joy out of the joke. Maybe I’m naive, but I’ve been to countless comedy shows and never once stopped to think about whether what I was hearing was 100 percent accurate until that Hasan Minhaj piece came out a few weeks ago in the New Yorker.

In mid-September, the esteemed magazine published an exposé essentially fact-checking some of Minhaj’s bits, and it found that some of his stories didn’t quite happen the way he describes. In his 2017 Netflix special, Homecoming King, he says his white female friend rejected his invitation to the prom when he went to pick her up for the dance because her parents didn’t want her taking pictures with a Brown boy. The woman in question, who’s been harassed online and doxxed since the special came out, told the magazine she actually turned him down a few days before. In another timeline fudge the New Yorker uncovered, Minhaj says he visited the Saudi Arabian Embassy the same day Saudi journalist, dissident, and author Jamal Khashoggi was killed, when it was actually about a month before.

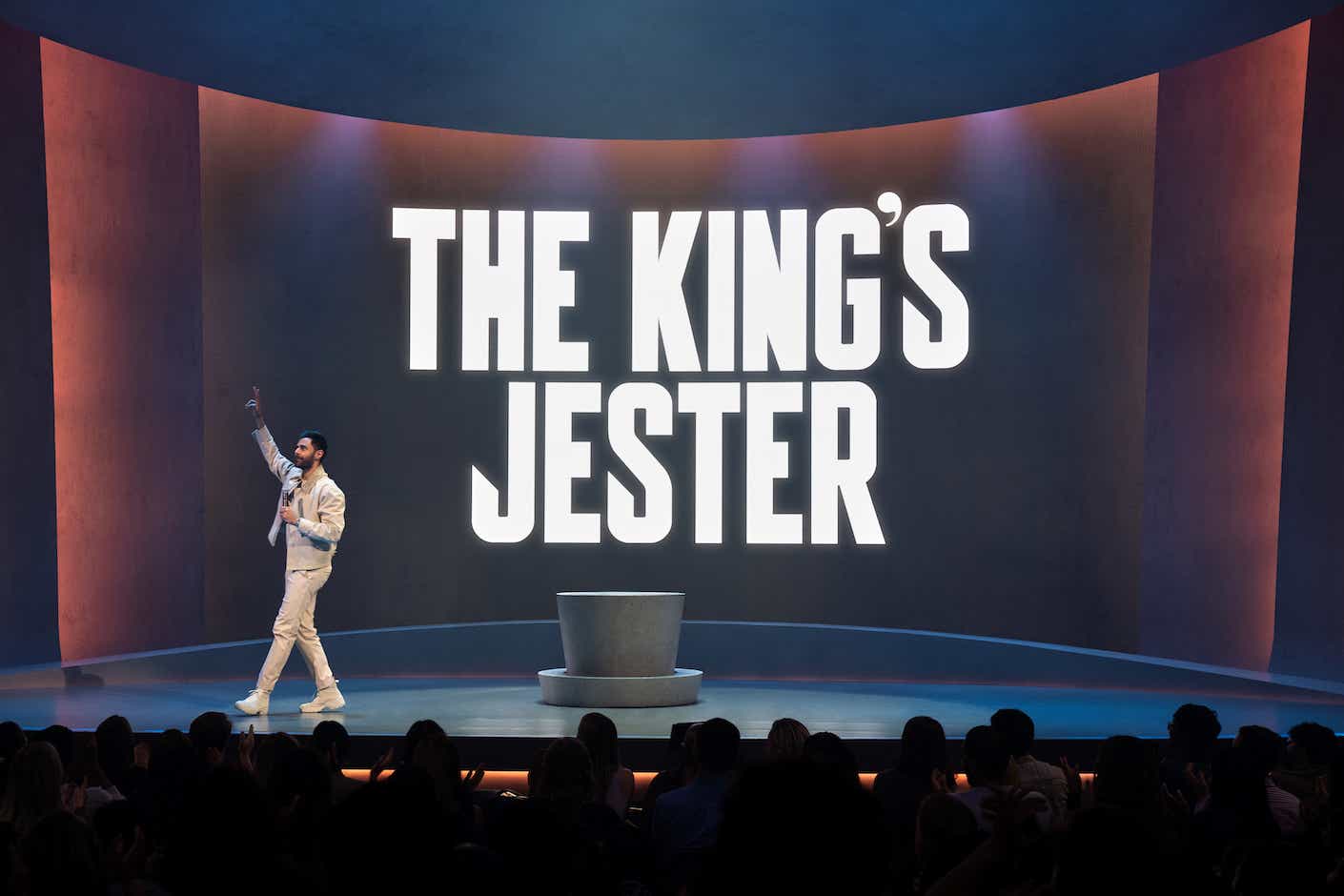

There are other stories that didn’t happen the way they’re told. In his 2022 Netflix special, The King’s Jester, Minhaj tells an extended story about an undercover FBI agent who went by Brother Eric (real name: Craig Monteilh) infiltrating his mosque in an attempt to elicit confessions of terrorism. According to his story, Monteilh reported Minhaj’s mosque to authorities, leading police officers to show up at the mosque and pin Minhaj to the hood of a car. The New Yorker revealed Minhaj’s mosque was not infiltrated when he was growing up, and certainly not by Monteilh, who was in prison at the time. (Minhaj said the Brother Eric story was inspired by “a hard foul he received during a game of pickup basketball in his youth” with middle-aged men whom the boys suspected were officers.) In another anecdote, he rushed his daughter to the hospital because she was exposed to anthrax that was enclosed in a piece of hate mail addressed to the comedian. Minhaj admitted that it, thankfully, didn’t happen, but said the story was based on once receiving a real letter containing a “powdery substance.”

Truth in comedy

It’s generally accepted and understood that comics will take some creative liberties in the pursuit of a joke, exaggerating or changing certain events to make them funnier. “That’s what we do,” Whoopi Goldberg said on a recent episode of The View. “We…tell stories and embellish them. Why would we tell exactly what happened? It ain’t that interesting.” Minhaj told Vanity Fair, “All my stand-up stories are based on events that happened to me.” Maybe the particulars weren’t exactly as he described, but he says the broad strokes are the same.

What complicates this argument, however, is that Minhaj sometimes blurs the line between comedy and journalism. He’s been a correspondent and temporary host on The Daily Show and he frequently uses his comedy to make larger social and political points. In The King’s Jester, he says, “I want to be able to switch between satire and sincerity and trust that you know the difference.”

The difference appears to be largely in the delivery — he’ll transition from his signature bemused, energetic delivery into a more somber tone. He occasionally uses visual aids (like news clips of “Brother Eric”) to illustrate his points. So when he’s telling the audience a disturbing story about an undercover FBI agent trying to befriend him as a teen, and identifying that person via name and video, it’s not necessarily intuitive that we’re still in satire — it feels like sincerity. It feels like he’s showing evidence to back up a point.

And while comedians seem to agree that exaggeration for the sake of a joke isn’t unheard of, with the exception of the Brother Eric story (which is an extended joke that contains multiple punchlines throughout), the so-called “untrue” moments the New Yorker cites aren’t necessarily making a story funnier. They’re done to elicit sympathy or raise the stakes.

That part is where the ethics of it come into question. “I think it’s maybe a little unethical to make something up or exaggerate to a large degree for the purpose of making a statement. To me that’s different [from a comedian exaggerating to make things funnier] and not super different from what conservatives do to rile up their bases,” says New York-based comedy writer Benny Scheckner, who is a “huge fan” of Minhaj.

Avery McKinney, an LA-based comic, understands the appeal of making these kinds of embellishments, even though he personally disagrees with doing it. “When you own these powerful stories, you get a very direct line to the audience,” he says. “It’s very electric, intense, and important and has gravity to it.” But exaggerating for effect, he feels, “sort of cheapens it — the experience is profound because it happened to you.”

The pressure to exaggerate

Confessional storytelling comedy is having a big moment: Nanette, The Great Depresh, Baby J — these are all specials where comedians open up about something terrible that happened, like depression, drug addiction, or the reality of being LGBTQ and gender-non-conforming.

“For so long these topics were taboo and now finally, storytellers and comedians and songwriters and whoever can finally write about this sort of thing,” New York City-based comic Sarah Adelman says. “A lot of people relate to these stories.” On the other side of the same coin, she says there can be more of a motivation, or even pressure, to center one’s comedy around something bad or dramatic that happened to them.

JPB Gerald, EdD, educator who writes about the intersection of race and language, says that for people from marginalized groups, that pressure only increases. “White audiences, at least most of them, don’t really want to hear what we have to say about just our lives. They only want to hear what we have to say in relation to the systems that oppress us.”

McKinney, who is biracial, will usually bring that fact up on stage. “It’s something I obviously think about a lot every day and it informs my experience.”

“But if you’re a white comedian, especially a white male comedian, there’s no pressure to talk about the white experience,” Dr. Gerald says. McKinney agrees, “I do think people have different expectations for different races and different genders.”

Comedy as education

Comedy has long been used to offer larger societal criticisms — or “punch up,” in industry-speak — but comedy as a means of disseminating the news, à la The Colbert Report or SNL’s “Weekend Update” only emerged in the early 2000s. Minhaj’s comedy is interesting because it combines personal storytelling with a political bent. He uses (what the audience believes to be) personal anecdotes to make larger arguments about policy, legislation, and prejudice. Minhaj told the New Yorker that these liberties are all taken in pursuit of a higher purpose. “I think what I’m ultimately trying to do is highlight all of those stories, building to what I think is a pointed argument.”

Using first-person narratives to drive home a bigger point can be an effective technique. “It’s hard to just talk generally about systems overall, because nobody necessarily cares. If you’re speaking broadly, it’s not that compelling,” Dr. Gerald says. In order to make it more engaging, especially for the purposes of something like stand-up, “you do have to get individual to some extent.”

But some critics argue it’s precisely because Minhaj is building to said argument, that he has a bigger responsibility to tell the factual truth.

“His audiences had signed up to be told the truth, and he’s being disingenuous — and reductive about the art form — to suggest otherwise,” Brian Logan wrote in The Guardian. Jason Zinoman wrote in The New York Times, “When stories told about racism, religious profiling or transgender identity are exposed as inventions, that can lead to doubt about the experiences of real people.”

Others say the particulars don’t matter as long as the points he’s trying to make still hold up. “There is nothing in these larger points that isn’t true when considered in light of the broader communities Minhaj represents, even if he sometimes tells stories that didn’t happen to him,” Sophia A. McClennen writes in Salon.

Scheckner says that while, as a fan, he felt betrayed by the revelations, there is room for forgiveness. “I think he could regain my trust by finding a smart way to address this and interrogate within himself what it meant on a personal and professional level that he lied to his audience.”

Minhaj doesn’t feel he manipulated audiences and told Vanity Fair, “I use the tools of stand-up comedy — hyperbole, changing names and locations, and compressing timelines — to tell entertaining stories. That’s inherent to the art form. You wouldn’t go to a haunted house and say, ‘Why are these people lying to me?’ The point is the ride. Stand-up is the same.”