This review was reprinted from Fresh Hell, Tina Brown's Substack, with permission.

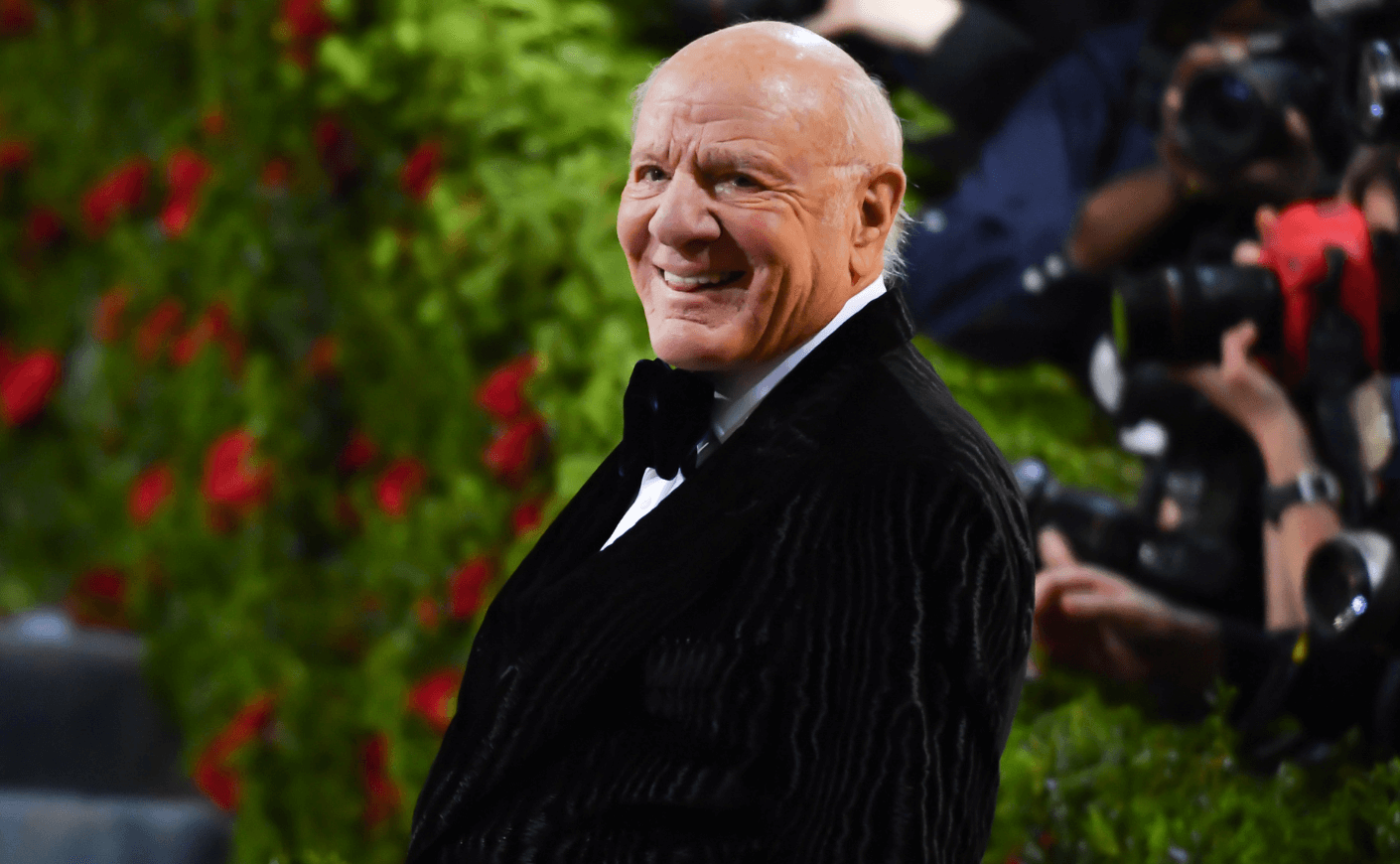

I first met Barry Diller in March 1985 at a Swifty Lazar Oscar night party at Spago, Wolfgang Puck’s hyper-fashionable restaurant on Sunset Strip. As the new editor of Vanity Fair, it was my first Oscar party hosted by the bald, kinetic gnome Swifty, the literary agent who never read a book, leaping around in his oversized black glasses, rasping social directives at the stream of celebrities and wannabes. I came upon Diller, then the youthful honcho of Fox Studios, crammed up against the bar with the likes of Michael Caine, Dennis Hopper, and Jacqueline Bisset. He was surveying the glittering riptide with suave amusement. “It's important to stay just past midnight,” he told me. “That’s when the bullshit all somehow metastasizes and you see Oscar night at its best.”

It was a typical Diller observation: knowing, iconoclastic. He’s always the savant at the heart of the action. I’ve never met anyone with a more independent mind than Barry. In the late 90s, Disney CEO Michael Eisner, whose career Diller launched when he hired him at ABC, used to invite friends and colleagues on overseas cycling trips. We got used to seeing Barry regularly turn left when the rest of the group was turning right, pedaling off on some secret route to get to the French auberge before everyone else. I doubt that he has spent more than one minute in his life with someone he didn’t want to speak to, or that he’s ever been slowed down by the pedestrian exigencies of travel. He avoids the Manhattan lunchtime traffic by speeding through it on a Vespa. Before his private plane lands, a steward knows to offer him, like a plate of hors d'oeuvres, two battered pairs of loafers from which to make his choice. Cruising the Mediterranean in his epically beautiful, 305-foot yacht Eos, he appears and disappears to his study below deck like the Cheshire Cat. Look up from lunch mid-conversation and you will see the back of his tonsured head speeding off in a tender to go snorkeling.

Over the four decades of our friendship, his ruthless honesty and wit are what I have come to savor about Barry most. He’s devoid of bullshit. When my husband, Harry Evans, sought his opinion about taking over as president of Random House, Diller counseled him, “There is nothing to protect against except going out of business.” Once, discussing the mystique of the entertainment mogul Lew Wasserman, he reflected, “There's great dust in his wake.” Diller is a comms legend for the terseness of his statement at a press conference when his bid to buy Paramount was trounced by Sumner Redstone. “They won. We lost. Next.”

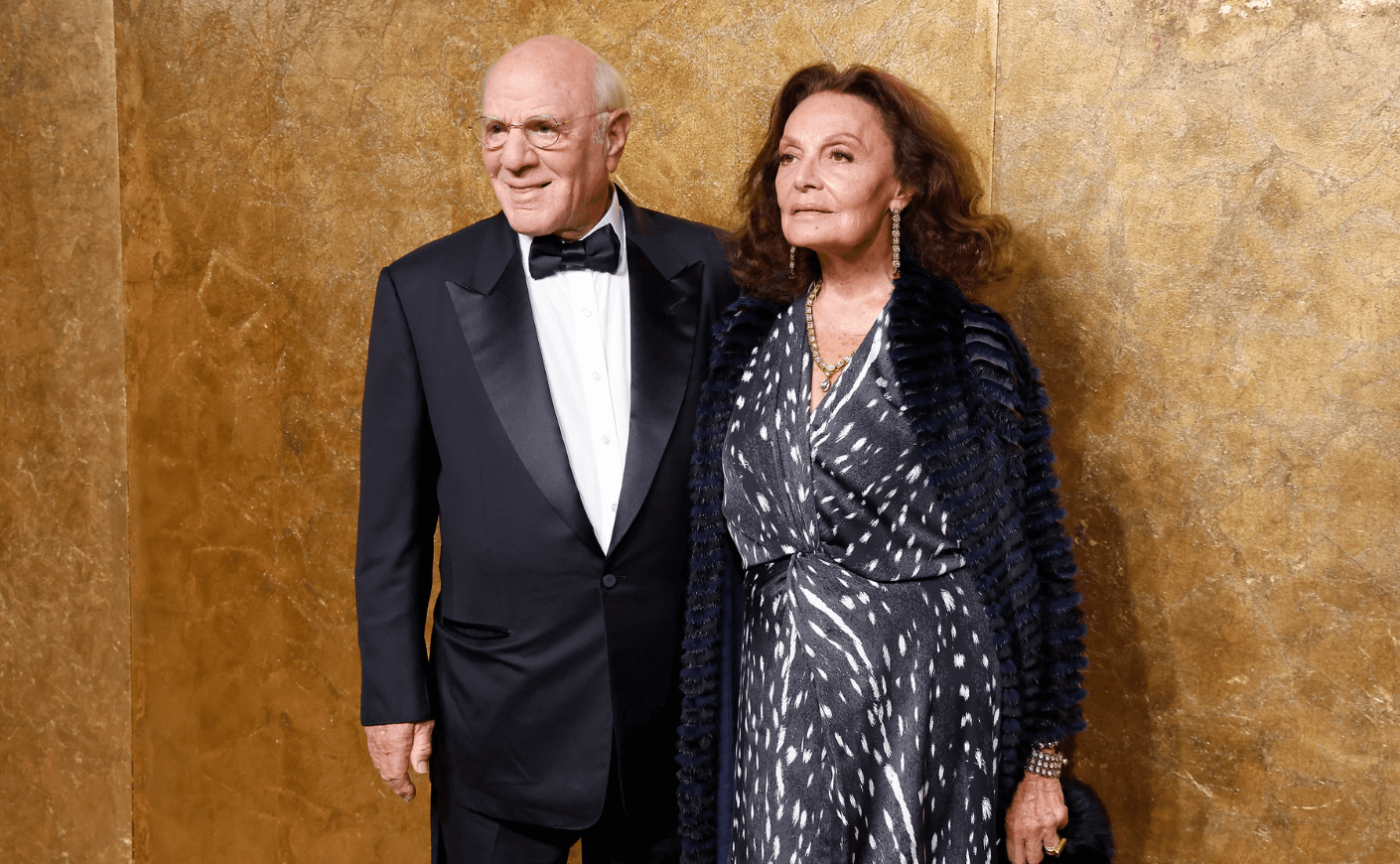

That’s why I was excited when he told me a few years ago that he was toiling over a memoir, without a ghostwriter. Would his inimitable, pungent observations translate to the page? The answer, now revealed in Who Knew, is a glorious yes. But would his candor include the full picture of his life, including his sexual orientation? Diller never hid that he was gay, but he never discussed it either, a decision he describes in the book as his “personal Bill of Rights.” “I would live with silence, but not with hypocrisy.” That silence precluded any explanation of his decades-long affair and then marriage to the iconic fashion designer Diane von Furstenberg, often seen as some kind of “arrangement” or friendship. He blows out this misconception with a detailed affirmation of the sexual charge between them when they first met and the essential bond they have sustained for fifty years. A sorceress of warm, cosmopolitan sophistication, who, even in the most relaxed of circumstances, always looks dazzling in her silk print muumuus and explosive hair, Diane never asked him to forfeit his other “secret” life, which wasn’t a secret anyway in all the circles they moved in. In private, it’s clear they have the kind of elemental connection that allows them to complete each other’s sentences.

His propulsive memoir goes some of the way to explaining the origins of Diller's unique self-reliance. His childhood and young adult terror of his homosexual orientation being “found out” made him fearless in every other aspect of his life. There was only space in his psyche for that one overweening dread of being outed. Other challenges he could skydive through with a maverick self-confidence that came from being on his own in every emotional respect. He describes how, as a child, he was bafflingly ignored by both his self-involved parents. As he bleakly writes, “My mother didn’t mother me, my father didn’t father me, and my brother didn’t brother me.” He was raised in the “pocket square of Beverly Hills, cosseted from life outside its tiny manicured borders,” by parents who didn't bother to come to his high school graduation or discuss where he might go to college. (He dropped out of UCLA after three weeks.) He was severely bullied by his drug-addicted older brother, who was killed at the age of 36 in a police incident. Some memoirists might have offered a more tender reconsideration of a sibling’s travails, but Diller refuses to pretend that he forgives him. His brother was the one possible ally in the void of his home life and he chose to tyrannize Barry instead. Basta.

Once we’ve traveled through the grim genesis of Diller’s lifelong apostasy, he launches into the gripping tale of how he left that early misery behind and began his hurtling ascent. Finagling a starter job at the age of 19 in the William Morris Agency mailroom through the patronage of the “Talmudic” Danny Thomas, famous comedian dad of his school friend Marlo, Diller swiftly realizes he has no desire to be an agent, a supplicatory job based on the whims of others. “You essentially lie for a living; you lie to your clients, who are being rejected; you lie to producers and directors and buyers of movies and shows — it can’t help but corrode.” But what he discovers during a photocopying assignment in the dusty shelves of the company basement are many decades of William Morris files that prove a goldmine of industry knowledge. For three years, Diller contrives not to be promoted as he goes to school on the history of William Morris transactions, inhaling every detail of how the entertainment business works: the deal points, the negotiation tactics, the contractual trip wires between stars and agents and studios. It was a self-tutored MBA in the details of process, which became the north star of his approach to business, “my one true mantra."

Having sat in business meetings with Barry when I worked for him at The Daily Beast, the online news site we created after he scooped me up from my face plant with Talk magazine, I can attest that his drill-downs, or “creative conflicts” as he likes to call them, are ball-shriveling to any executive whose logic has holes. You are expected to go mano a mano with him to prove the validity of your point, but your point soon disappears from memory in the fusillade of “So what?” and “Where’s this going?” or, the one I most dreaded, “This makes no sense.” A disconcerting trait is his ability to turn rapidly through seven pages of figures and stab at one dissonant line item. “This!” he demands triumphantly. “What’s this?” Our friendship survived.

In the current era of snowflake office culture, it’s refreshing in an almost transgressive way to read in his memoir about what ingenuity, risk-taking, work ethic, and bullet-train velocity it took to get Barry to the pinnacle of the entertainment world so fast. Vaulting into a job as an assistant to Leonard Goldberg, the head of programming at ABC network, Diller didn’t ask for opportunities, he just grabbed them, never forgetting his power base was being the world’s best assistant to Goldberg. “I always wish I had me for an assistant,” he muses ruefully. So do we all. Two of Diller’s transformative ideas were for the network to make an original Movie of the Week, a portfolio expected by many to fail, but which turned into a smash-hit concept, and the never-before-tried format of the multi-part miniseries, an idea that gave birth to Roots, the most successful ratings phenomenon in the history of television.

Perhaps because his own father was such a disengaged figure, Diller always hankered for the patronage of the colorful mastodons of the entertainment world like Arthur Krim, Darryl Zanuck, Otto Preminger, and Steve Ross, whom he could cast as the emotive father he longed for. “They were as theatrical in their means and methods as were the films they put up on the screen.” A king-size cartoon character in the book is the chairman of Gulf and Western and Paramount’s owner, Charlie Bluhdorn, a combustible Austrian energy ball, who appointed Diller, at the stunningly young age of 32, as Paramount’s chairman. At warp speed, Diller, so versed in TV culture, had to master a whole new entertainment genre in the movie business. People magazine published a story about him titled “Failing Upwards.” (“Better to be called a failure than a fairy,” he reflects.) Over the next ten years, Diller rewired and re-energized Paramount, deploying his rare combination of executive skills and cinematic taste to foster a golden era of hits including Saturday Night Fever, Reds, Terms of Endearment, and Beverly Hills Cop, until the fatal day in 1983 when his mentor Bluhdorn died and was succeeded by the C-suite snake Martin Davis. One of the juiciest aspects of Who Knew is Diller’s willingness to share all the conniving and politics that went into his rocket to the top. It includes his lethal strategy to assert dominion over Paramount, taking control from its two biggest hitmakers, Frank Yablans and Robert Evans, who thought that, after the massive success of their movies The Godfather and Love Story, the studio was, as Diller puts it, “wired to their egos.”

As a former editor, I’ve always felt that you can teach someone how to write a lead, but not how to notice the telling details. Diller notices the telling details. Martin Davis, he says, “was a dour Uriah Heep-type character, who heckled from the shadows.” Jeffrey Katzenberg, whom Diller hired as his assistant at Paramount, “was compact and wiry with the work intensity of a beaver on speed.” Marvin — as opposed to Marty — Davis, the obese, fraudulent owner of Fox, who conned Diller into leaving Paramount to run the going-broke Fox Studios “sat in the most oversized chair I had ever seen.” All the alpha monsters come alive in his book.

Perhaps the only power chess player commensurate with Diller is Rupert Murdoch, the great white shark of the media industry who got control of Fox in 1985. It takes a seducer to know one. “The hot bath of [his] enthusiasm is something extraordinary,” Barry admits as he succumbs. This time, Diller’s bold idea was to launch an edgy fourth TV network, Fox Broadcasting Company. It stumbled and bled cash at first until he found a sitcom in 1987 that “lit [his] contrarian spark and came to define what Fox was,” Married… with Children. It was followed in 1989 by TV's now longest-running animated series, cash cow, and savior of the new network, The Simpsons.

But Diller had met in Rupert the ultimate grand master. It was the level of Diller’s success at Fox that meant he was now expendable to Murdoch, who also resented Diller’s acclaim. For five years, the two titans occupied adjoining offices and a convivial Rupert wandered in and out. But from the moment Diller tells him he wants to be a partner in the business, one hears from the other side of Murdoch’s now rarely open door the rising strains of the theme music from Jaws. “This is a family business,” Rupert told him clinically, “and you’re not a member.” It was the ultimate rejection for the man still seeking a father figure. Diller had come to his sliding door moment, when the true nature of power was revealed to him. Unless you are an owner, you’re a hired hand. He beat Murdoch to the punch and quit Fox, the company Diller had built with such passion and imagination.

In February 1993, I assigned writer Ken Auletta a story for the New Yorker titled “Barry Diller’s Search for the Future.” It described Diller’s contemplative solo road trip from a dinner with Steve Jobs in Palo Alto to a visit to the MIT Media Lab in Cambridge, as he pondered his next act. Diller wanted, among other things, to fully explore the promise of the internet. It took visionary nerve (and not caring what anyone thought) for someone whose career had been steeped in the glamor of the most thoroughbred Hollywood studios to make his first entrepreneurial acquisition the mass-market home shopping network QVC, based in West Chester, Pennsylvania. He had the last laugh. QVC was his entry into the paradigm-shifting concept that the technology of entertainment, of shopping — of everything — could and would be interactive, not just one-directional. Thirty-three years and many acquisitions later, IAC, the powerhouse conglomerate Diller built of online shopping, travel, and dating businesses, is housed in a white glass galleon of a building in downtown Manhattan, designed for him by Frank Gehry. Being an owner does something for you that being the most celebrated executive never will. And becoming a billionaire is no doubt the best revenge of all.

These days, enveloped in contentment with his beloved DVF and her family that is now his own, Diller spends more and more of his time aboard Eos, only investing in cultural and philanthropic projects that excite him. “I never see a plane taking off that I don’t want to be on,” he writes. The outsized footprint of his legacy includes the High Line, the spectacular elevated park on Manhattan’s West Side, and Little Island, the Hudson River park and cultural center he conjured into being. Diller remains brilliant at curating his own relevance, still presiding at the top of the bill at Herbert Allen’s annual Sun Valley Conference and still mentoring young turks. Back in 2019, he put AI genius Sam Altman on the board of Expedia Group, where Diller is chairman.

The big dogs who dominate the headlines now look very different from Diller’s heyday — spectrum-y tech bros like Zuckerberg and Bezos (a close friend of Diller’s) whose trainer-built musculatures don't look as though they quite fit their biology, or Musk, who always looks as though he's wearing the wrong thing, no matter what he puts on. They could not be more different from Barry, a voraciously curious, world-traveling sophisticate, who looks born to wear a suit, but whose inner life is just the opposite. In the book, he says he regrets he wasn’t brave enough to own his sexual orientation sooner, but perhaps he did something braver. Eschewing the playbook of shame-ridden sneaking around in a then-homophobic world, he demanded to be accepted on his own terms, creating a superstructure he could dominate, bend to his will, and give him a life in which he was never less than who he wanted to be. There’s great dust in his wake.