There is very little that most would consider “normal” about Chrysta Bilton’s childhood.

She was raised by a gay single mother in the late 80s when such parenting arrangements were exceedingly rare. She was conceived using a sperm donor, a one-time Playgirl model who Bilton’s mother met by chance while getting her hair touched up in Beverly Hills. Her early life was marked by wild instability: One month they’d be sitting pretty, living out of a sprawling L.A. estate thanks to one of her mother’s lucrative stints as the head of some mid-level-marketing scheme, the next they’d be facing eviction. Then there’s the kicker: Bilton learned only in the past few years that she has around 40 biological siblings…and counting…and she might have dated one of them.

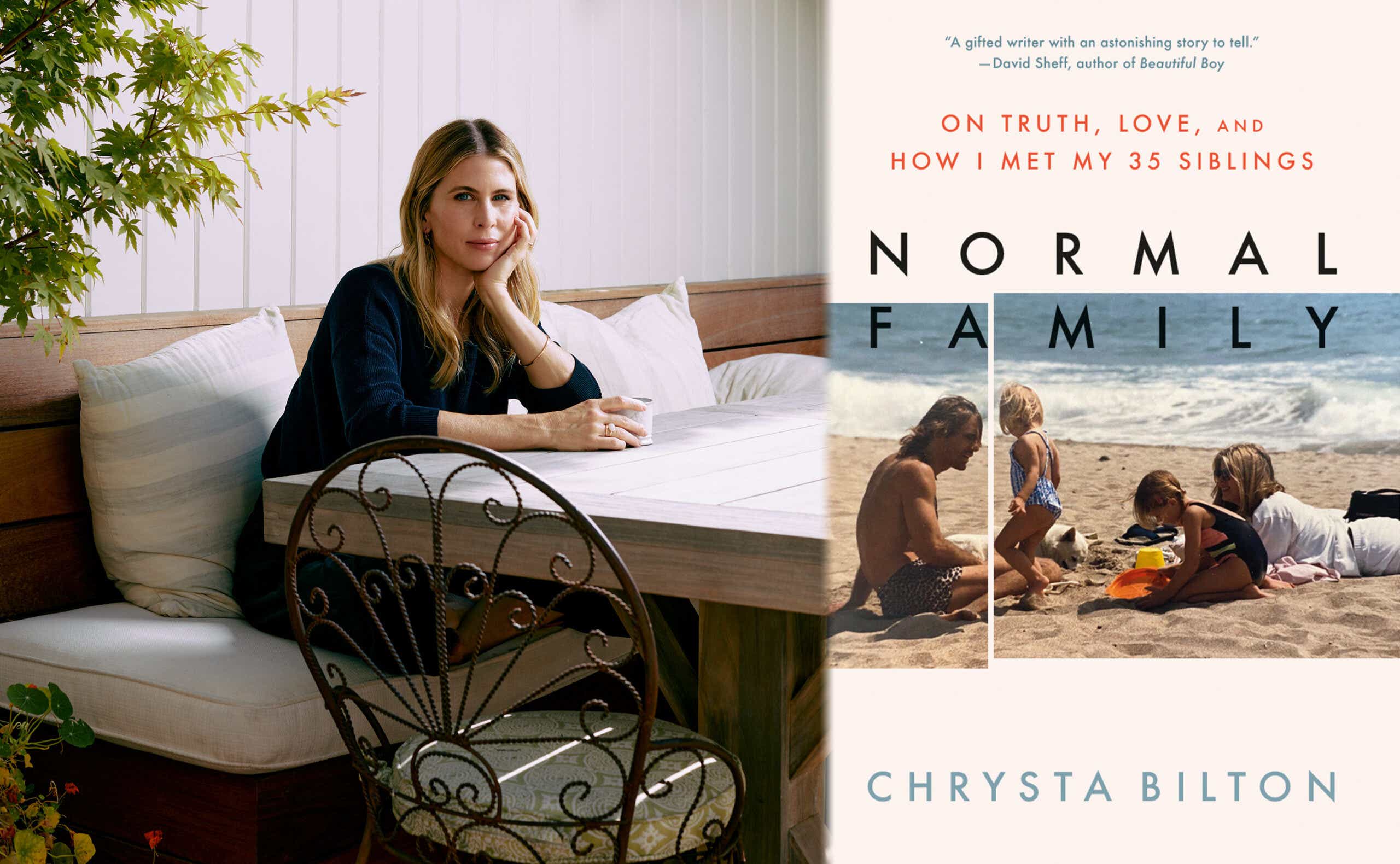

She covers all this and more in her wildly entertaining new memoir, Normal Family. The book is a rich account of her rather unconventional upbringing, that’s both a “love letter” to her mother and an effort to uncover and interrogate her family’s full history — warts and all, Bilton tells us. We spoke to the author about her ever-evolving concept of family, processing inherited trauma, and the shifting politics of sperm donation.

KCM: What made you want to share this story?

I think I originally wrote the book as sort of a love letter to my mother, even though there are some sections where she comes off as somewhat flawed. It’s about what it was like to grow up with her in L.A. in the 80s and 90s a gay woman, setting out to start a family at a time when she didn’t know anyone in her community who had kids. And then it also explores this idea of what makes a family, because my conception of my family was ever-changing — and grew to be even more so when I discovered this larger biological family.

Can you tell us what went through your head when you first learned that you may have other siblings?

That was the first tipping point in me realizing that a lot of what I had been told wasn't true. Shortly after my mother told me about the siblings, I got a Facebook friend request from one of my biological sisters, and I think at the time it was just too overwhelming for me — the idea of having one new family member, let alone possibly dozens. So at that point, I just couldn’t deal with it and largely shut the fact of this biological family out of my mind. It would be almost a decade later that I changed my mind.

At the same time, your mother told you that your boyfriend at the time was possibly your half-sibling. How did you process that?

That was a lot. I think that some people who pioneer for donor rights and limits on how many kids are born to one donor will talk about the possibility of biological siblings unknowingly dating each other. But it’s much different to live that experience. I think if I had written this as fiction, no one would have believed it could actually happen. It was so beyond the scope of what I would have thought a possibility that there was some cognitive dissonance there. Looking back at photos of him and then thinking about the times we’ve been together and trying to analyze his facial features to question is he for sure my brother, is he not my brother? — it was a lot, to say the least.

It was also complex because he had a close relationship with the father who had raised him, so I didn’t feel it was my place to go and discuss it with him and potentially unravel this large family secret. So I was a little bit on my own in processing that.

Did you contact your mother's sperm donor at all to gather his input?

I did. The interesting thing about my biological dad is that even though he’s sort of in a different reality now [Bilton’s father has struggled with substance abuse and mental illness], when talking about the past he’s very lucid. But because I had been told a lot of what my mother would have called fibs about my conception and my family, I was going on a journey of reporting what had really happened by talking to them and comparing their stories.

In a way, I hoped the book would read a bit like a mystery because it was a mystery to me. So I thought putting readers through that same psychological experience would be more emotionally true.

Do you know if he has read the book?

My biological father has not read the book. But he has read all the press around the book and he sends it to me constantly. [Laughs] He corrected me about one fact that I’m thinking maybe I’ll add as a note in the paperback edition. I had said that among his many conspiracy theories was that aliens were coming to Earth to harvest women’s eggs. He corrected me — and the correction is way crazier than that. [Laughs] But overall, he’s been really sweet about the whole thing. He said that he’s very happy with the way that he lives and that it might not be a common existence, like living in his car and being nocturnal and taking care of various animals, but it’s a happy existence. And he just wanted me to get that across.

You touch on inherited trauma in the book and write pretty extensively about your mother and biological father’s difficult childhoods. How would you say it impacted your own upbringing?

I think that one of the blessings of a difficult childhood is that if you're able to get out of it, you just feel so grateful. I have so many blessings in my life now that I don't really look back on it with any anger or resentment, and have come to a place where I can also appreciate all the good things. I think every family has its complexities, but I did have some challenging material to work through. And understanding what they went through was a large part of coming to understand who they were and how they carried out some patterns which have run through their own families.

What advice do you have for others who are learning about and dealing with family trauma later in life?

A big theme in my book is shame. I think a lot of people who come from homes with a lot of trauma or alcoholism or mental illness, a big component of that feeling of shame is thinking that there's something flawed about themselves. And thinking that if people knew about whatever issue it is that they wouldn’t like you or you’d be unlovable. That was something that I struggled with a lot. What I hope is that from telling my story others learn that that’s just not true and it helps enable them to open up. A big lesson in the book is just embracing your truth and being proud of where you come from — with the good and the bad — and not working so hard to hide it. Because that can really cut you off from other people.

You wrote in the book that you had found 30 some-odd siblings. Where does the count stand now?

I think we’re about 40. And continuing to grow. Because you know, back in the early 80s and 90s doctors routinely advised parents to keep it a secret. So the way we’ve found out about siblings is because one of them will randomly decide to take a DNA test — usually not knowing that they were donor-conceived. And those tests, even though they’re growing in popularity, still aren’t that common.

Most of us think there are probably at least 100, just because my father donated for almost 10 years. I think he estimated that he donated about 500 times and each of those donations is split into multiple sellable vials. The sperm banks didn’t track all the people that those went to and which ones resulted in a pregnancy, so there’s really just no telling.

What has your relationship with your siblings been like so far?

It’s wonderful now. As I said, when I discovered the fact of this large biological family, it was too much for me emotionally at the time and I didn’t want anything to do with them. Then a few years ago, a random encounter with one of my sisters changed my entire attitude about the whole thing. And now I have close relationships with several of them, and I see it as a really rich, beautiful part of my life that was completely unexpected.