In the annals of halftime show history, there's one performance that did more than just making an impression on the audience — it left a wardrobe malfunction-shaped dent in pop culture. The 2004 Super Bowl halftime show, starring Janet Jackson, had everyone talking, texting, and blushing in their living rooms. In this excerpt from the new book Toxic: Women, Fame, and the Tabloid 2000s (published by Abrams Press), author Sarah Ditum brings you a tale that goes beyond football — a story where fashion meets fumble, and the Super Bowl halftime show takes an unexpected plunge into pop infamy.

Ninety million viewers would see Janet Jackson perform live on February 2, 2004. That’s ninety million people who would be exposed to her music — some for the first time — and who might become fans and ultimately buy her records or go to her concerts. In the end, it was ninety million who saw her bared breast in a fumbled costume reveal that transformed her from the personification of sexual empowerment into a global avatar of indecency — and inadvertently changed the way we consume media forever. This is Nipplegate.

If it hadn’t been for the boob, Janet would probably be remembered as the best bit of an otherwise sketchy halftime. In an interview with MTV before the show, her choreographer had promised “some shocking moments.” But as the performance approached its end, there was little sign of its delivering anything that would be memorable for the right reasons.

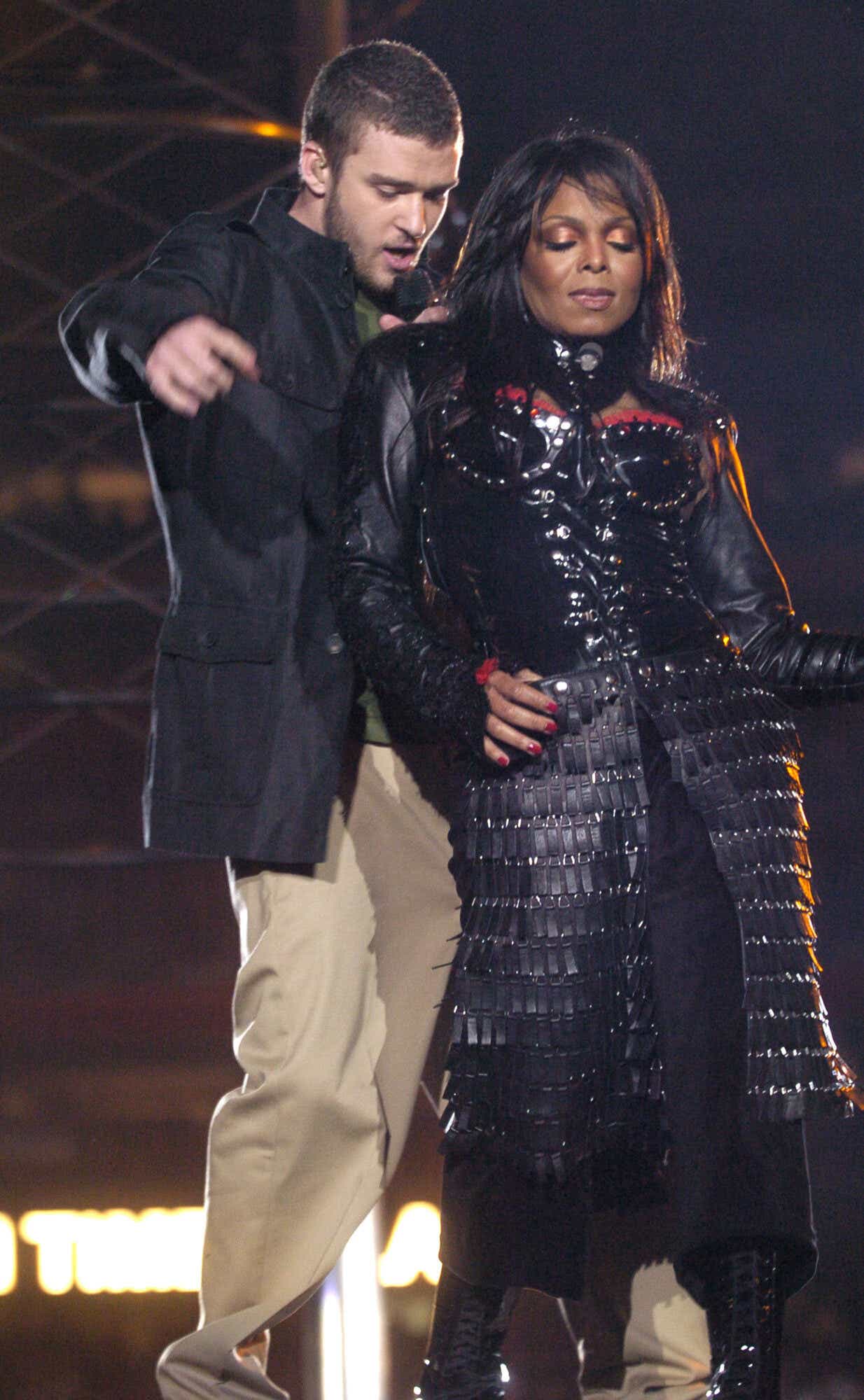

Janet did her first number, “All for You,” wearing a pirate-inspired costume designed by Alexander McQueen. Her glossy black bustier had nods to fetishism, with a built-in choker and red lace trimming the cups, but the outfit was remarkably modest by the stripper chic standards of female singers in the aughts, thanks to three-quarter-length trousers and full-length sleeves. It was also modest by Janet’s own standards, considering she had once appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone with only a pair of male hands covering her breasts.

Following Janet, P. Diddy and Nelly came onstage and delivered a breakneck mashup, involving dancers who whipped their skirts off on command. This was followed by Kid Rock thrusting his hips while roaring his own name and wearing Old Glory as a poncho. For more conservative-minded audience members, this was uncomfortable viewing — and it was, of course, about to get much worse. Janet returned to the stage for “Rhythm Nation,” and then Justin Timberlake emerged through the floor, and the two began a performance of his song “Rock Your Body.”

Janet was thirty-seven and had been in show business for thirty years, which made her the definition of established. She was the youngest of the nine Jackson children, all of whom had been cultivated for fame by their father, Joe. When she was fourteen, Joe arranged a contract for Janet with A&M Records; the result was two lackluster pop-soul albums. After that, Janet cut professional ties with her father and moved to Minneapolis to work with Prince associates Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis. The album they made together was called Control, and it went to No. 1 when it was released in 1986. Control’s title was a statement of intent: This was a woman who ran her own show, both creatively and sexually. Sex was part of the way she showed she wasn’t her daddy’s little girl anymore.

Janet was a true crossover star. Rhythm Nation 1814, wrote Joseph Vogel in a twenty-fifth-anniversary appreciation, “positioned a multifaceted, dynamic black woman as a leader, as someone whose ideas, experiences and emotions mattered.” Nonetheless, it was the sex part of Janet’s image that had dominated in the years after Rhythm Nation 1814. In a Rolling Stone interview, writer David Ritz asked, Was the sex all a publicity ploy? No, she replied: “Sex has been an important part of me for several years. But it just hasn’t blossomed publicly until now.”

By the time she made All for You in 2001, the “blossoming” had reached full bloom. The song “Would You Mind” included lyrics so provocative that some retailers felt compelled to add parental advisory stickers. (Eventually, her label, Virgin, issued a version with the offending track cut.) None of this outrage did anything to stop All for You from becoming Janet’s fifth No. 1 album in a row.

But by the time she performed at the Super Bowl in 2004, All For You was three years in the past. There were questions about her relevance. Thirty-seven was considered perilously mature in an industry that worshiped youth to the point of having established a virginity cult around Britney Spears. So, it was important for Janet to show that she still had it, and playing Mrs. Robinson to the world’s hottest young heartthrob seemed like a very effective way to do that.

Timberlake was dressed more conservatively than Janet when he arrived onstage, in slacks, T-shirt, and jacket. It made him a slightly incongruous addition to her show — the plumber on a call to a fetish club. He pursued her, she strutted and teased, and as the song reached its climax, they stood together on a riser at the center of the stage, in full view of the world. “Talk to me, boy,” she cooed at him, and he sang a promise back to her: “Bet I’ll have you naked by the end of this song.” Then he reached across her torso, grabbed the right cup of her bustier, and pulled.

And this is the moment when something seemed to go wrong. In the dress rehearsal, Janet had worn a detachable skirt for Timberlake to snatch away, but no one had been happy with the result, and the reveal was taken out of the choreography. Following that, Janet’s costume designer had spent the day of the performance making hurried alterations to the outfit, and just before showtime, Timberlake had been summoned to Janet’s dressing room for a last-minute conference. No one has ever disclosed what was said at that meeting.

What ought to have happened, according to Janet’s spokesman after the event, was that the outer fabric of the bustier should have detached, leaving the red inner layer in place. What actually happened was this: latex and lace came away together in Justin’s hand, and Janet was left, breast out, in the full glare of the cameras — a “wardrobe malfunction,” in the language both her camp and Timberlake used in their initial apologies. Only a sunburst-shaped nipple shield covered her — and if anything, that made it worse, because it implied premeditation. But Janet’s face suggested this was not quite how the performance had been planned.

She looked down at her chest and appeared immediately stricken, while the show plowed grimly on around her. At the back of the stage, oblivious to the world-changing flash that had just taken place, an array of pyrotechnics went off, while Janet clutched a hand — too late — across her breast. The timing was excruciatingly, appallingly perfect. Then the sponsor’s chirpy message came in: “Thank you for watching the AOL Top Speed Halftime Show!” It was the perfect punch line to the moment’s horrible comedy. Of course, it had to be sponsored by an internet service provider, because the internet was the third reason that Nipplegate became the nightmare it did for Janet.

***

Two days after the Super Bowl, the BBC reported, “Janet Jackson’s breast has become the most searched-for image in net history.” A spokesman for the search engine Lycos said that Nipplegate had received sixty times as many searches as the Paris Hilton sex tape, eighty times as many as Britney Spears, and more even than the previous record for most searches in a twenty-four-hour period, which, according to the article, had been held by 9/11. People didn’t just want to see Nipplegate once; they wanted to see it again and again and again. The flash, the fireworks, the thrill of outrage.

TiVo revealed that it was the most replayed moment in the service’s existence, and it drove a flurry of sign-ups. In a time when it was hardly difficult to find pictures of breasts to look at, there was something irresistible about this one breast in particular — and about the whole concept of the “wardrobe malfunction,” an expression that immediately entered the lexicon.

A lot of people believed the costume had functioned exactly as intended. “Gosh, what a happy coincidence . . . that her costume just happened to have a breakaway bra cup,” snarked Washington Post TV columnist Lisa de Moraes. It was hard to take Janet’s claim to be a victim of pure accident seriously, not only because the moment appeared to have been planned in some degree (as Janet’s eventual explanation about the costume confirmed), and not only because she was renowned for sexual provocation, but also because the teasing display of female flesh was in fashion in the aughts. Like Paris’s sex tape, such moments fell into the compelling overlap between “she was asking for it” and “she didn’t want this.” The exposure was only possible because the woman had chosen to wear something exposing; it was only titillating because we, the viewers, got to see something that she hadn’t chosen to expose. This was so compelling that, according to one of YouTube’s founders, Nipplegate had inspired them to create the video sharing service. The appetite to see Janet’s humiliation helped to reinvent the media.

From the book Toxic: Women, Fame, the Tabloid 2000s courtesy of Abrams Press © 2024 Sarah Ditum