We've all been struck by a book that consumed our thoughts and inspired ongoing reflection. (Which is, ideally, what all the best books should do anyway.) That's what happened when Elvis Costello — yes, that Elvis Costello — read Tom Piazza's latest book, The Auburn Conference. The premise of the novel is heady stuff: What if, during a late-1800s writer's conference, legendary scribes like Mark Twain, Herman Melville, Walt Whitman, and Harriet Beecher Stowe all rubbed elbows and discussed the state of the union? The questions they examine along the way have plenty of relevance to not only the tumult of the country post-Civil War but to 2023, too.

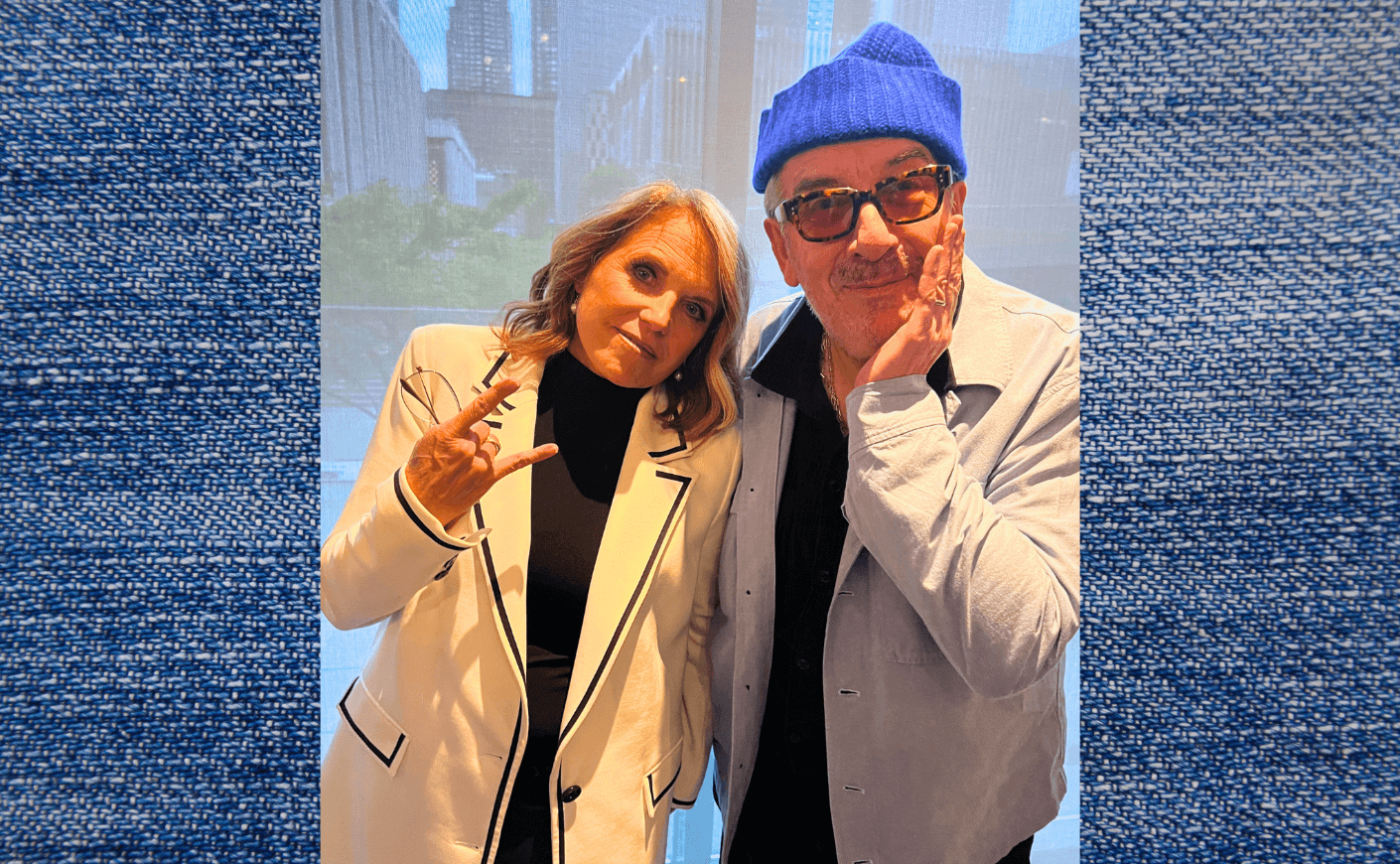

Katie and I met Costello at a recent event (see the shot of the two of them, above), and he mentioned Tom, The Auburn Conference, and how much he'd enjoyed the book. I wanted to know more about how the two creatives came to connect, so I asked him for all the details. It turns out that the friendship between Costello and the Piazza pre-dates the book — and that the two met in the midst of an artistic project of a totally different sort. "Tom and I met on the set of Treme, for which he was writing," says Costello. "David Simon's series was set in the wake of Katrina; Allen Toussaint and I had completed the recording of the song 'The River In Reverse' while New Orleans was still under curfew, so my cameo appearance was actually based in fact — I was a member of the audience at the club Vaughans in the 9th Ward, where Wendell Pierce's character was playing with great Kermit Ruffins. It was a long shoot, so Tom and I had plenty of time to talk and discovered not only that we knew all the same people, but might have been friends all along."

As to how Costello became aware of the book, he told me he'd had a backstage pass of sorts to its creation. "I had responded to a questionnaire in The Guardian, one of those 'What is your favorite film, record, toothbrush, and flavor of ice cream?' features," says the singer. "I listed The Auburn Conference as a book that I'd been reading in installments as Tom finished them. In a roundabout way, that little pop quiz set a process in train."

The imaginary 1883 writers' conference that serves as the book's backdrop explores issues around what it means to be an American. So I pointed out that, of course, this question is as central today as at any time in our country’s history — and asked Costello what he sees as the responsibilities of citizenship.

"That's perhaps a question for my American-born sons," he demurs. "You could say I'm a real-life 'American Revolutionary'; I pay my taxes but have no vote or 'representation' as such. Actually, I carry a passport of a different hue and could probably be asked to leave at any moment." But he did offer up thoughts on the threats to our democracy: "If you ask me as an observer or outsider, I'd say the greatest enemy is cynicism; the willingness to say or do any wicked thing to advance your cause or platform. Let's just say it's getting harder to love your enemy."

One of Costello's best-known songs is "(What's So Funny 'Bout) Peace, Love And Understanding," so I had to know: Are there lyrics he's written that express his mood on the state we find ourselves in? "Well, I once wrote a song imagining a man, who resembled P.T. Barnum, selling souvenirs of a concert tour that he promoted in 1850," he says. "It's called 'Red Cotton' because, like many commodities, it's stained with somebody else's blood. This is only just dawning on the song's narrator as he sings:

'The Lord will judge us with fire and thunder

As man continues with all his blunders

It's only money

It's only numbers

Maybe it is time to put aside these fictitious wonders'

He adds, "I like Tom Piazza's writing because he has a compassionate sense of what went before and its consequences. You can't simply reach back into the past to correct or erase what you don't like about it but — if you are still permitted to do so — you may read it, understand it, and even sing it out loud:

For man is feeble

Man is puny

And if it should divide the Union

There is no man who should own another

When he can't even recognize his sister and his brother"

Finally, I asked Costello the question that's been on my mind, and the minds of so many friends and family members: Does he expect to support a presidential candidate in 2024 — or is there someone he'd like to see make a bid? Costello was poetic and slightly cagey: "I am put in mind of the lines Herman Mankiewicz wrote for political operator, 'Boss Jim W. Gettys' in Citizen Kane: 'If it was anybody else, I'd say what's going to happen to you would be a lesson to you. Only you're going to need more than one lesson. And you're going to get more than one lesson.'"

Below, Elvis and Tom chat about the themes of the book, how it took shape, and what celebs and luminaries might be invited to an "Auburn Conference" if it were held today.

Elvis Costello: I am neither a scholar nor even a very avid reader — I have only an everyday awareness of Melville or Twain — yet I found this book completely compelling and accessible. What would you say to readers who might fear they lack the literary knowledge to appreciate the nuances of The Auburn Conference?

Tom Piazza: I’d say, ”Jump in.” The Auburn Conference is a novel, not a historical tract, and any reader can enjoy it without a guidebook or footnotes. If the book makes a reader interested in Walt Whitman or Frederick Douglass, or the parallels between 1883 and 2023, that’s all to the good.

We spoke frequently while you were writing this book, and I remember your delight when Emily Dickinson wandered into the frame unnoticed and unnamed. These famous literary figures are not seen solely through the lens of their reputations; they're first encountered in the mundane process of arriving at their lodgings in Auburn, with their foibles and vanities and frailties all on display. They seem like guests that you invited into this narrative. Did you ever consider inserting an “outsider” to the American literary scene into the Conference? Did any of your invited “guests” steal your towels, surprise or disappoint you once you had them within the walls of your story?

Mark Twain’s African-American banjo-playing friend Henry might be considered an “outsider.” He was the central character in my previous novel, A Free State, and he makes a cameo appearance here with a performance that delights most of the white attendees and upsets Frederick Douglass. Henry might be an outsider to the literary scene, but performers like Henry have always been central to the American cultural scene. And in reciting a soliloquy from Othello between selections on the banjo, he shows himself to be culturally amphibious, to say the least.

Probably the biggest surprise for me was the delegation of women Suffragists invited by the nameless but very ambitious reporter. He has a vested interest in stirring the pot, and he’s good at it. “No reporter,” he says in Chapter 5, “ever earned a name filing stories headlined ‘CALM SEA OFF NANTUCKET.’ ” He probably would have stolen the towels if I’d given him a chance. But the Suffragists are an insurrection of their own — incensed, with good reason, that they had not been invited by the organizer to participate, and insistent that the question of women’s rights be addressed. I was glad they showed up.

The Auburn Conference — set, as it is, in 1883 — takes place before recorded sound could be mass-produced, before moving pictures, and before photography could be easily reproduced in newsprint. The authors at the Conference achieved remarkable fame almost entirely through the power of their thought and published words or — like Frederick Douglass — their public oration. Could there possibly be a viable “Auburn Conference” today, and who would attend it, other than reality show stars, social media influencers, or tech billionaires?

I don’t know that there could be. Writers occupy a different place in society today. Social media and the 24-hour news cycle have made for a flattening effect in the culture. Everything is at the same volume level, and all the ambient noise of loudly asserted, and often unearned, opinion makes it hard for anything to stick. Each of the writers in The Auburn Conference has a highly individual, original voice. The questions they debate are as alive today as they were then, if not more so – the nature of democracy, the future of the country, the role of the writer.

The members of the generation or so of writers who came of age during or just after World War Two – James Baldwin, Allen Ginsberg, Norman Mailer, Toni Morrison, Joan Didion, Saul Bellow, Ralph Ellison, Philip Roth – all had powerful, distinct voices, and they still took the idea of the American project seriously. I’m not sure we have that anymore. We are drowning in pundits whose remarks evaporate as soon as the next headline shoulders them out of the way.

In a funny way, I think a new Auburn Conference might look to performing songwriters for the urgency of expression those 19th-century writers showed. Bob Dylan might constitute an Auburn Conference all by himself. He contains multitudes.

Many of your books are concerned with music, whether portraits of singular performers or as a form of currency in your novel A Free State, in which musical talent is a strange kind of passport, the cause of envy and imitation. In The Auburn Conference, the appropriate musical starting point might be the desire to achieve a “polyphony” before striking several “dissonances” and descending into “cacophony.” Is it stretching too far to imagine the author taking a baton before an orchestra each day as you were writing this book?

An orchestra’s coherence depends on a written score, but the writing of The Auburn Conference was improvisational, not planned out. I had a loose provisional “program” in mind, but it was always subject to change and surprise, even disruption. Anyway, I never knew, at any given point in the writing, exactly where or how things were going to play out. I never felt as if I was directing the participants or telling them how to relate to one another – they all had strong ideas of their own! Maybe the real musical corollary is found in all the necessary sensitivity to the musical dimensions of prose itself – tension and relaxation, loudness and softness, texture, pitch, pace, and rhythm.

Walt Whitman, Mark Twain, and Frederick Douglass were all, to a considerable extent, constructs of their own making. Two of the conference panelists are antagonists of your own invention; “Lucy Comstock,” a wildly successful romance novelist of little literary consequence or even apparent vanity, and Confederate General Forrest Taylor, peddling his memoir and the myth of “The Lost Cause.” Without courting any libels, were there any specific volumes of bad romantic fiction or objectionable Confederate memoirs on which you based the characters of “Lucy Comstock” and “Forrest Taylor”?

If I were to start listing examples of “bad romantic fiction,” past and present, I might meet an untimely end. It’s a perennial genre. I will say that the character Lucy Comstock is smart, resourceful, extremely successful, uncompromisingly practical, and under no illusions about her books’ literary ambitions. She would do very well in today’s corporate-driven literary market.

The character Forrest Taylor is based closely on the Confederate general Richard Taylor, son of former President Zachary Taylor. Richard Taylor wrote a Civil War memoir titled Destruction and Reconstruction, in which seething anger and resentment simmer underneath an elegant, wry literary style. It was published in 1879, after the final Federal troops were pulled out of the South and the initiatives of Reconstruction were being suppressed, often violently, ushering in the barbarities of the Jim Crow era.

I'm curious about why The Auburn Conference takes place in 1883 and not, say, 1877, a year of disputed elections and a series of deeply regrettable compromises. I wondered if this date was chosen because it was the “last possible moment” for this cast of characters. Melville is seen as disillusioned; admired by the idealistic organizer of the “Conference” but declared mad by some critics. Harriet Beecher Stowe is a couple of years away from a descent into dementia. Even the three most dynamic presences in the cast, Twain, Whitman, and Frederick Douglass are known to have suffered episodes of great melancholy or psychological collapse. How key was it that both the nation and the cast of writers are so openly displaying these fissures in your choice of 1883 as the year in which the “Conference” takes place?

I started writing The Auburn Conference during the run-up to the 2018 U.S. midterm elections when we were all asking ourselves the same questions the conference’s organizer was asking himself 140 years earlier — “What are we doing with the freedom we have earned? What is an American? What, ultimately, is America?”

The writers at the Conference were all young when the nation was young, and they had seen things come to a crisis over the issue of slavery. The Civil War was fought to settle large questions, but those questions remained with undiminished urgency. The nation had to live with warring versions of what had happened, and why. The country as a whole never seriously addressed the aftermath of slavery once the North shrugged off the suppression of Reconstruction in the 1870s and beyond.

Melville and Whitman nearly come to blows arguing over whether America was, finally, a land of grand possibility, or if our need to cut moral corners and forget important facts was steering us inevitably toward a ditch. Twain, in his final address to the audience, even suggests that the word “Amnesia” should replace the word “Liberty” on American coinage. And Frederick Douglass’ fiery response to Forrest Taylor’s remarks precipitates a riot.

But in terms of lifespan and health, as you say, it was certainly late in the game for this combination of characters. Still, Mark Twain is reinvigorated by the proceedings and leaves the weekend ready to finish The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, which he had laid aside several years earlier. Melville leaves with the germ of Billy Budd in mind. And Lucy Comstock uses her aborted dalliance with Forrest Taylor as a springboard into her new novel.

A frivolous question to end: If this book should ever require a movie poster, it might read: “The Auburn Conference! The Great! The Ruthless! The Notorious! America Discussed! Hilarity Ensues!” Would the actor playing Frederick Olmstead Matthews, the idealistic young professor who conceives this gathering, resemble you at all?

Well, “young” would be the first casting hurdle. Beyond that... I don’t think I could write a book — or a good book, anyway — without finding some resonance of myself in each of the characters, even the bad actors. But like the young organizer, I can’t help believing in the possibilities in the democratic experiment. I’m stubborn about that.