You’ve heard the slogan “don’t mess with Texas,” but there’s a new force brewing in the Lone Stone State by the name of Alicia Roth Weigel, an author, healthcare and policy consultant, human rights commissioner for the city of Austin, and intersex activist who is making waves in the LGBTQIA community. You may have seen her on the Peacock documentary Every Body or heard her on Jonathan Van Ness’s podcast Getting Curious. But her real work has only just begun.

“The I in LGBTQIA actually stands for intersex, but up until now, it might as well have stood for invisible because our community has not gotten a lot of opportunity to be seen and heard,” she tells us.

Katie Couric Media caught up with Roth-Weigel to learn more about what people misunderstand about her community, the surgeries many intersex children are subjected to without their consent, and why she decided to come out in front of the Texas legislature.

Tell us about the intersex community. As you’ve mentioned, a lot of people don’t seem to be aware of what it means to be an intersex individual.

We're not a small community. Somewhere around 2 percent of the world is born intersex like me, which means we're born with physical sex traits (which could be anything from chromosomes, hormones, internal reproductive organs) and external genitalia that doesn't fit neatly into the male and female binary that you traditionally see as the only two options on birth certificates.

People are starting to understand that sexuality is a spectrum: There are men, there are women, and there are non-binary people. What folks have not really started to learn yet is that sex is not binary, either. Intersex people like me are born somewhere in between the two poles of that spectrum. And again, we're not rare. There are actually about as many of us as there are people who are born with red hair or green eyes. We have just been living in the shadows, and it's time to change that.

You didn’t even realize you were intersex until later in life, right?

Growing up, I was always told that I had complete androgen insensitivity, which is my intersex variation. Intersex is more of an umbrella term; it encompasses a lot of different types of bodies that are somewhere on the spectrum between male and female. My particular variation of complete androgen insensitivity, or CAIS, basically means that I am insensitive to androgens, or what most people would refer to as male hormones. I have XY chromosomes, which many people associate with being a man, although I was also born with a vagina. And instead of being born with a uterus and ovaries on the inside, I was born with internal testes.

The reason that I look the way I do despite having XY chromosomes and everything I just mentioned is because my body does not really respond to testosterone. So my testes would've produced testosterone, and my body would've converted a lot of that to estrogen and then urinated the rest of it out. What's really interesting is a lot of cisgender women process more testosterone than I do.

There's a diversity of types of bodies, and it's not as neat as our elementary school biology textbooks have led us to believe. But the world likes things to fit into neat little boxes, and rather than society acknowledging that people like me exist and changing the boxes on forms to accommodate our existence, we are forcibly altered to fit our bodies into one of those neat little boxes.

Why did your parents decide to remove your internal testes in infancy?

The rationale that my parents were given to remove my testes was that I could get testicular cancer one day…and that is true. Anyone who has any body part could get cancer one day. All human beings have skin; therefore, we could all get skin cancer. However, my risk of getting testicular cancer as someone with complete androgen insensitivity is actually somewhere between 1 and 5 percent, which is pretty low. A lot of cisgender women are born with the BRCA gene, which predisposes them to breast cancer or ovarian cancer at much higher rates than my potential risk of testicular cancer. However, you don't see doctors forcibly removing little girl’s ovaries or breast tissue without their consent. But that's what happened to me.

They called the surgery a gonadectomy. I call it castration because that's what they did — they took my testes without asking me. Yes, they were on the inside of my body, not on the outside. But I think it helps to strip away the euphemistic terms and talk about what actually happened; it impresses upon people the level of violations of human rights that our community faces.

After I was castrated, my body no longer had the hormone-producing organs that I was born with, so I went into hormone withdrawal ever since infancy. For most other people, our hormones start to accelerate when we're entering puberty. My body didn't have that opportunity because my hormone-producing organs were taken from me without my consent in childhood. That meant I had to take external hormones to induce changes that would have occurred naturally had my body been left intact. And throughout all of this, I was never told, “You were born in between.”

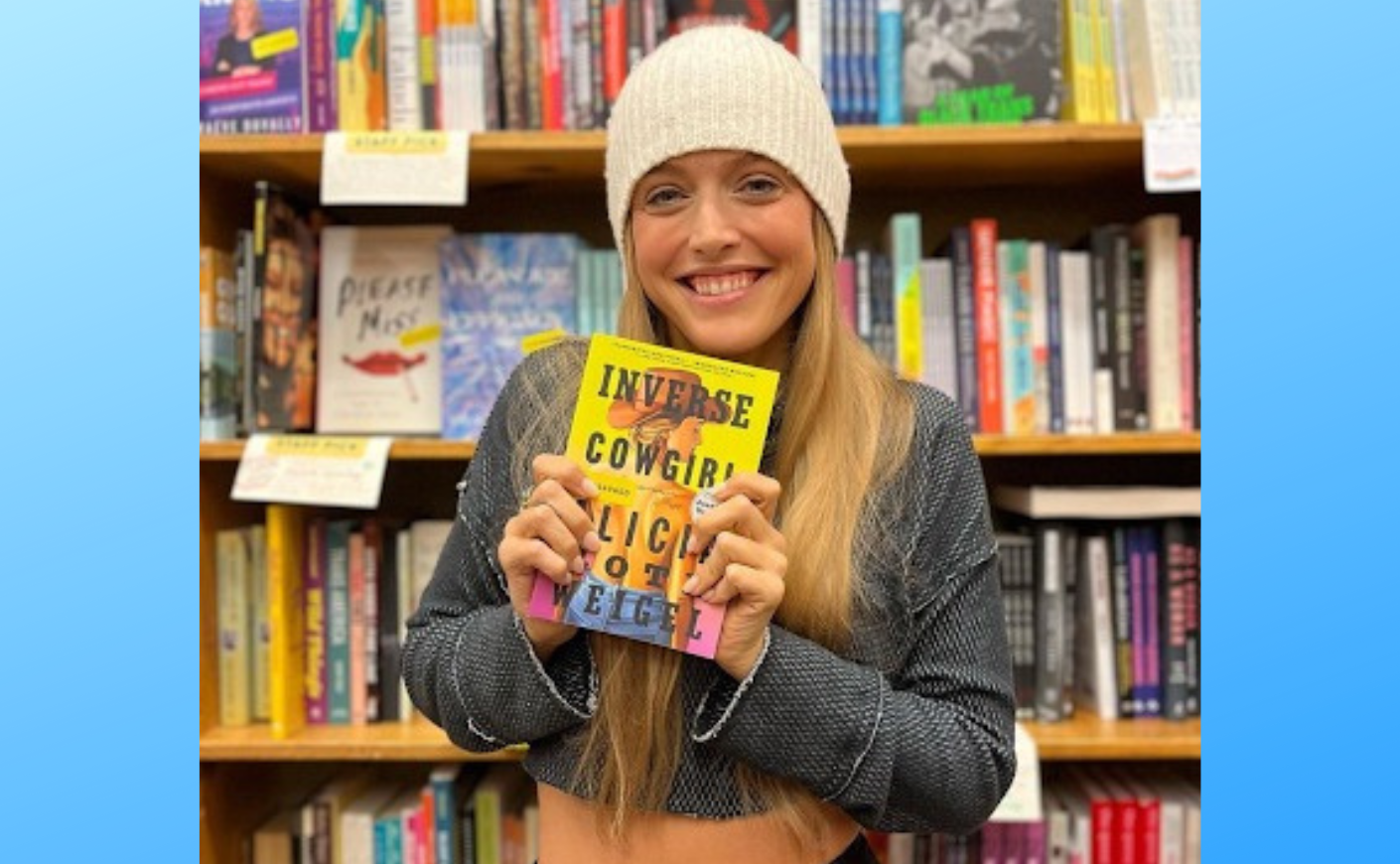

Tell us about your new book, Inverse Cowgirl.

I decided to write this book because I was visiting a friend who took me to a bookstore with a “trans, intersex, and gender" section. I was like, oh my gosh, there's a section with the word intersex on it. I'm so used to seeing no representation of intersex people in culture at large, whether it be in books, movies, or on TV. I looked through every title, and there was not one intersex book. I broke down crying because I felt so unseen. It wasn't just about that moment in the bookstore; it was so illustrative of society at large, where if intersex people are not seen, we are not heard. And if we are included, it's usually in a very token way, like just throwing a letter into an acronym.

Real inclusivity is about meaningfully finding ways to understand someone else's humanity and then including that in the way we operate in the world. I wanted to give people an opportunity to do that. Sharing stories helps people understand a lot better than reading a short article. Instead of a highly medicalized version of the intersex experience, I want to share a real-life experience of what it means to be an intersex human.

But Inverse Cowgirl is also bigger than that. I started writing this book the day that Roe v. Wade was overturned because now half of the United States understands what it's like to not have control over your own body and the decisions that you make over your own body. That's something that intersex people like me have understood since infancy, since these very first surgeries that we have suffered without our consent that drastically affect the trajectory of the rest of our lives. I think we're uniquely positioned in that way to be leaders in the fight for body autonomy more broadly.

Tell us about how your tattoos have become a practice of your therapy.

As intersex people, we are told that our bodies are inherently flawed and unlovable — that they're gross and they're undesirable. I wanted to reclaim my body for myself and not have a relationship with it based on how doctors told me to view myself. Getting physical ink of things that I find beautiful — not what someone else has told me is beautiful — has helped me reclaim my own skin. I decided to use that as a roadmap for my book, anchoring each of my chapters in one of my tattoos, both to help share my story and also to make that point that we all deserve to feel safe and happy and beautiful in our bodies.

You came out as intersex very publicly and received a lot of attention for how you did it. Tell us more about that moment.

When I came out in front of the Texas Senate for the first time, I hadn't even really thought about how being intersex would affect how I see myself and how I see the world. I was just so angry about how our representatives in Texas were using pseudoscience and misinformation to target people that I cared about, namely my transgender friends. They were trying to enforce this bathroom bill based on false logic. They were saying biological sex is cut and dry, and if we go back to that, then all these trans people will go back to where they came from. I wanted to tell them that if they want to pass discriminatory legislation, they should at least open a biology textbook first.

Since then, I've had to do a lot of the work associated with being out as an intersex person in the world. Intersex people don't just come out once. A person can say, “I'm gay,” and people will understand — but when you're intersex, the vast majority of the world has no idea what that means. Every single time it comes up, I have to explain my existence in a way that necessarily involves talking very openly and honestly about my body, and oftentimes involves dredging up childhood trauma. It's a lot.

Intersex people get used to being hyper-exposed, and there are a lot of ramifications from it. I won't claim that I have it all worked out and that it's always easy because, frankly, it's not. But I revert back to this quote that my mentor Wendy Davis always used to say, and it was actually quoting Lady Bird Johnson, who said, “Become so wrapped up in something that you forget to be afraid.” That's what drives me more than anything.

A record number of anti-LGBTQIA bills have been introduced in state legislatures across the country. One of these bills was the reason you were inspired to publicly come out. How are intersex issues intertwined with this new legislation?

The hottest-button topic these days is usually legislation that targets healthcare for transgender kids. There's this argument that's often used to propel bills that block gender-affirming care for trans people, which says that it's in the interest of protecting children. That being said, these same exact bills that block surgery and hormones for transgender children include specific language that says you can continue to enact those same surgeries and hormones onto intersex children who have never asked for them. So what these bills are saying is we can't give life-saving care to individuals who have begged for it and have shown high rates of depression and suicidal ideation when they are blocked from it, and yet we can continue to force that same exact care onto individuals who have never asked for it.

What does success look like for you in your advocacy work?

There are entire countries that have banned non-consensual surgeries on children until they’re able to meaningfully participate in conversations about their own bodies. In the US, we would love to see something like that farther down the line. Things are more complicated to move here than they are in smaller countries where these surgery bans have occurred, like Greece and Kenya.

One thing that we are trying to move in the US is legislation that provides public health education campaigns targeting doctors and parents of intersex kids. A lot of doctors receive maybe one line in a medical school textbook about intersex bodies, and that's it, which is wild because there are actually way more intersex people than there are trans people in terms of pure population numbers.

We need to collect more data on the intersex community to show not just the healthcare inequities that we face but also to find out what our bodies need to be healthy. But step one has to be making people aware. We can't solve a problem that folks don't know even exists.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.