The rise of commercial DNA kits has led to some earth-shattering discoveries.

There have been scattered news stories across the country of children using these kits only to find that their father isn’t actually their father, and in some cases, they’ve led to a much darker biological truth.

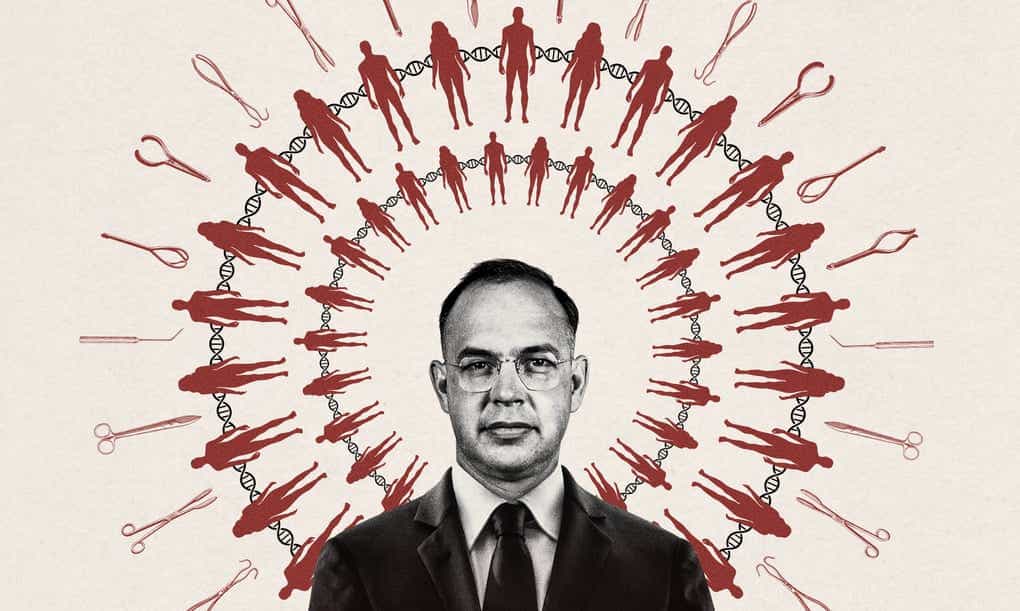

Director Hannah Olson’s directorial debut Baby God, which premiered on HBO on Dec. 2, follows the real-life story of Dr. Quincy Fortier, a fertility doctor based in Las Vegas. Considered a widely respected obstetrician, he was accused of using his own sperm to impregnate dozens of women without their knowledge or consent.

Fortier, who died in 2006 at age 93, was sued late in life by at least two patients for secretly using his sperm to artificially inseminate them but these cases were settled out of court and he never lost his medical license.

It was only after his death that he acknowledged in his will that he was the biological father to the four children of two patients who had sued him, according to the Las Vegas Review-Journal. That's not all — per 2007 court documents, Fortier left a footnote that acknowledged the possibility of more biological children being identified after his death.

As Olson’s documentary explores, many of the biological children are left to wrestle with their identity, and to what extent Fortier’s DNA has shaped them as individuals.

Take, for instance, one of the main subjects in the film, Wendi Babst. The retired police detective accidentally found out Fortier was her biological father after discovering half siblings through the Ancestry.com DNA test and website.

“Wendy was one of the first people I spoke to, and Wendy was also a big reason about why I chose Dr. Fortier because she said she was an investigator who just had the same curiosities that I had about what was happening, only it was much more personal for her,” Olson told Wake-Up Call.

“Every time she gets a DNA match, she knows that someone is going through the same thing that she went through,” she added.

Olson said she first came across Fortier while working as a producer on the popular PBS docuseries Finding Your Roots, which has helped celebrities, including Scarlett Johansson and Lupita Nyong'o, explore their family histories.

Upon further research, she learned that doctors covertly using their own sperm to inseminate patients happens more often than what some might assume.

“There have been so many doctors who have done this and they're always treated as like one off,” she said. As text at the end of the documentary points out, "More than two dozen U.S. doctors have been accused of secretly inseminating patients with their own sperm."

In a more recent case reported by The Washington Post, a woman filed a lawsuit after learning that her “anonymous” sperm donor was actually her own fertility doctor. But pursuing damages is often difficult in these kinds of cases given that there is no national law criminalizing what’s called “fertility fraud.” Even in states like Texas and California where there’s legislation explicitly outlawing it, these laws aren’t retroactive and the statute of limitations for many civil lawsuits has already passed.

“This is a crime that's revealing a set of attitudes that we have both about doctors and about women,” she said, noting that there’s still “this idea that doctor knows best and that the women don’t need to know.”

Olson underscored the importance of the #MeToo movement and its reexamination of sexual violence, saying fertility fraud is a form of assault and should be treated as such.

“It's a battery to put something in someone's body without their consent and it's malpractice,” she said.

She believes part of the problem is that there are no national laws governing the fertility industry. In comparison to many other nations, neither the U.S. nor state governments do much to oversee the multibillion-dollar industry. Though they are some sperm donation guidelines, there’s no mandatory limit to how many times a donor’s sperm can be used and sperm banks may not get accurate medical histories from their donors, who could pass along genetic diseases.

While the legal system still needs to further address how the fertility industry should be regulated, Olson said Fortier’s biological children and others like them are left to deal with the lifelong emotional toll of being genetically linked to their mother’s assailant.

“So many news stories focus on the act of the crime and not what happens after. And I think in this case, what happens after will go on forever and ever and ever,” she said.

This story was written and reported by Tess Bonn.