History is recorded in many ways — through written documents, stories repeated time and again in families, art and photographs that stand the test of time. But the American history that you learned from your classic high school history textbook was…let’s just say, not entirely accurate. Historian Ray Rafael reviewed 22 school history books and found that all were “culpable for serious lapses.”

So, we’re beginning to recognize that American history can be fuzzy at times — a truth that is especially evident when we celebrate July 4, as you'll see below. We’re here to do some serious myth-busting as we debunk falsehoods about American history.

When was the Declaration of Independence signed? Well, it wasn’t on July 4th

Yes, we celebrate Independence Day on July 4. But why? The reality is that the declaration of independence wasn’t actually signed on this day. Here’s the real story: Congress declared independence from Great Britain on July 2, 1776. Two days later, Congress approved the actual Declaration of Independence and sent it off for printing. On July 8, Colonel John Nixon read a printed version of the Declaration, marking the first time the public heard what was in the document. Finally, on August 2, members of the Continental Congress began signing the engrossed version of the Declaration.

It was only in 1870 that the U.S. Congress declared July 4th a national holiday. Perhaps, that means July 2nd and August 2nd should also be federal holidays. (We doubt anyone will mind two extra days off!) In fact, the Constitution Center says that August 2nd is “one of the most important but least celebrated days in American history “

Did Betsy Ross actually design and sew the first American flag?

Legend has it that widowed seamstress Betsy Ross deserves credit for the American flag. Too bad that’s not true. The first mention of Ross’ contribution to the flag was made by her grandson, William J. Canby, when he gave a speech on the history of the American flag. He claimed that the congressional committee appointed Ross to design a flag for the nation. Soon enough, newspapers and periodicals printed the story and distributed it across the country. Of course, we can’t blame the people for believing it’s true — we jump at the opportunity to credit a woman with a major historical moment!

The natural next question is — if Ross didn’t design the flag, who did? Some evidence suggests it was Francis Hopkinson, a naval flag designer who was once a member of the Continental Congress. In 1780, Hopkinson requested payment for his design of the U.S. flag and the Great Seal.

Even if Ross didn’t actually stitch the first American flag, her story is now stitched into the fabric of the nation.

The “Star-Spangled Banner” tune was not composed in America

In September 1814, the Maryland fort was being bombarded by the British as a continuation of the War of 1812. As dawn broke on September 13th, lawyer and amateur poet Francis Scott Key noticed that the U.S. flag was flying on the fort, declaring U.S. victory. At the time, Key was aboard a ship eight miles away. He then wrote a poem titled “The Defense of Fort M’Henry.” Soon, the poem appeared in newspapers across the country.

But, here’s where it gets interesting: The tune for the poem was not composed in the United States. Instead, Key chose the tune from the popular drinking song “To Anacreon in Heaven” by British composer John Stafford Smith. And that’s how “The Star Spangled Banner” came to be what it is today. Isn’t it ironic that the poem written to celebrate the United States’ victory over the British is set to a British tune?

Washington, D.C. hasn't always been the capital of the United States

The first Continental Congress was convened in 1776. And nope — it wasn’t in D.C. In fact, Washington, D.C. didn’t serve as the capital till 1800. For over 20 years before that, the U.S. capital shifted across multiple locations — Philadelphia, Baltimore, Lancaster, York, Princeton, Annapolis, Trenton, and New York. Washington D.C. was actually the ninth in the list of capital locations in the United States. And then finally, a permanent home for the capital was found in the U.S. Capitol in Washington D.C.

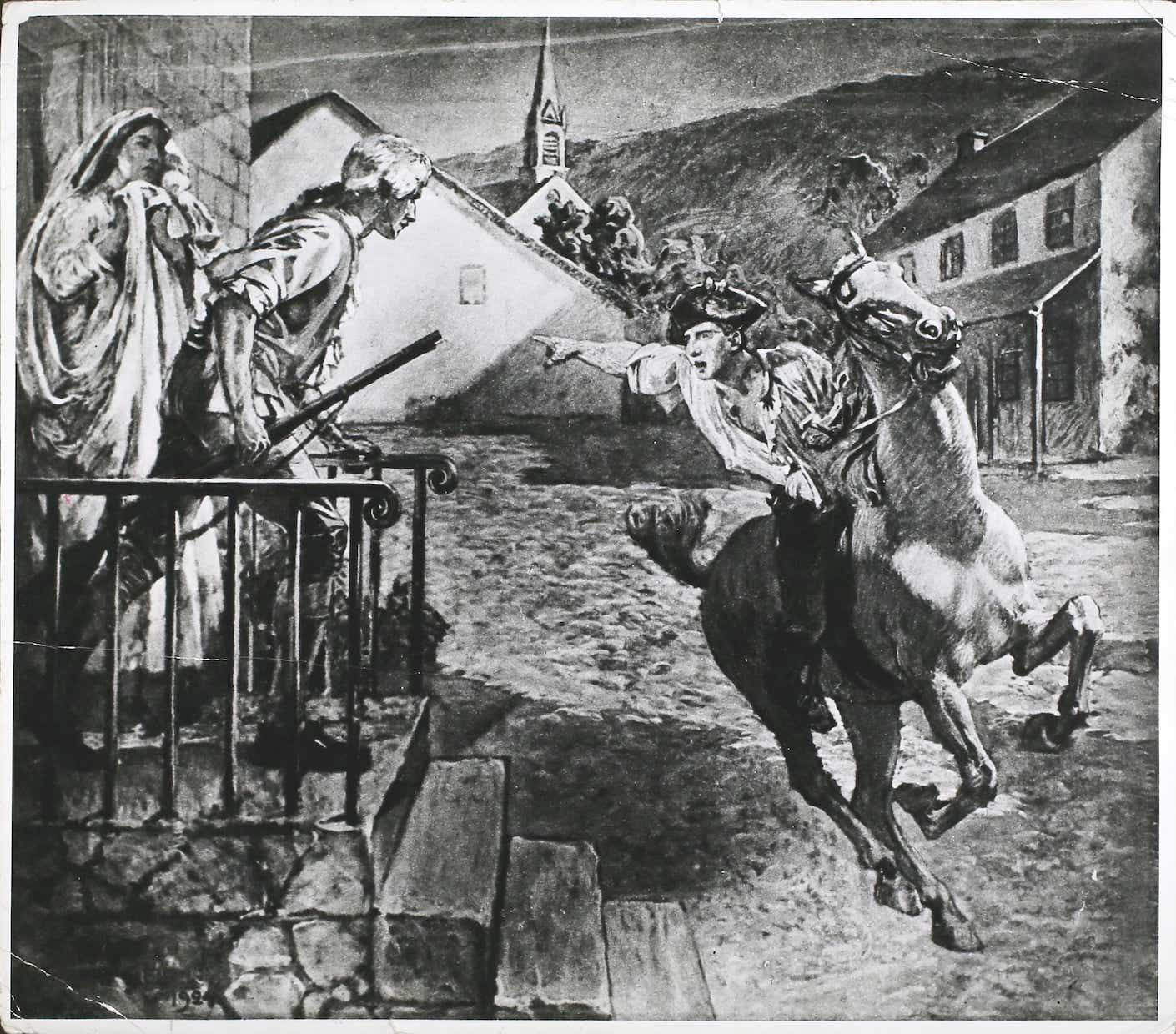

Paul Revere and the myth of “The British are coming!”

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow immortalized Paul Revere through his poem “The Midnight Ride,” making him an icon of American history. But, truth be told, the story we all have heard of Revere and his midnight ride on April 18th isn’t entirely accurate.

By profession, Revere was a silversmith. In 1765, he joined the Sons of Liberty and soon became a courier for the Committee of Safety. He would often carry messages about occupied Boston, monitor British movements, and relay information to Patriot leaders. On April 18, 1775, the British were about to set out on a mission to destroy and remove arms from the countryside. Revere was sent to convey the message to John Hancock and Samuel Adams, who could have been targets of the mission as well.

Age-old tales tell us that Revere passed through the towns on his way to Lexington, yelling “The British are coming!” However, in reality, he wasn’t quite saying that. In fact, it would be odd for him to say that since most people who lived there at the time (the colonial Americans) considered themselves British. Accounts show that Revere actually said, “The regulars are coming out.” The regulars was a term used to refer to British soldiers at the time. He traveled with two other men, William Dawes and Samuel Prescott, and they were later joined by as many as 40 men on horseback spreading word through Boston’s Suffolk County.

Well, at least the truth has come out now.