In the heady days of the 2010s, it felt like everyone on Instagram, Twitter, or Facebook was talking about being “cancelled” — or attempting to cancel someone. This social-media phenomenon was a form of banishment, a punishment for behavior that was deemed unforgivable by the masses (or whoever had the loudest voice on Twitter that day). That behavior might be anything from an off-color joke to support for the wrong political candidate. Cancellation was — and is — a way to seemingly achieve hard and fast erasure, and the repercussions range wildly depending on the subject and the circumstances. It might mean anything from a loss of social media followers, to a loss of jobs or endorsements, to even a loss of personal privacy.

But cancel culture isn’t unique to the modern age. And it might not always be the most effective way to hold someone accountable.

To understand the complexities of this extreme form of modern exile, let’s look at one such canceled person. In 1997, J.K. Rowling gifted the world with a book that’d go on to be beloved by readers of all ages and break records in the process. Her Harry Potter series became a worldwide, culture-altering sensation. Within a few years — and multiple bestselling books and blockbuster movies later — many would’ve considered Rowling’s position in modern literary history to be unimpeachable.

That was until she made allegedly transphobic remarks in 2019, after supporting a British professional who’d been fired for her anti-trans tweets. A year later, she mocked an article that said, “People who menstruate.” Rowling tweeted, “’People who menstruate.’ I’m sure there used to be a word for those people. Someone help me out. Wumben? Wimpund? Woomud?” Critics tagged Rowling a TERF — a Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminist.

But Rowling wasn’t one to back down — she responded with a 4000-word blog post that many deemed a “transphobic manifesto.” In it, she expressed her concern about the consequences of trans activism, writing, “I want trans women to be safe. At the same time, I do not want to make natal girls and women less safe.”

The response was a tidal wave of dismay: Harry Potter stars Daniel Radcliffe, Emma Watson, and Rupert Grint came out in support of the transgender community. The International Quidditch Association — which revolved around a game from the Harry Potter series — decided to change its name to Quadball, in an effort to distance itself from the now-controversial author. Rowling also did not appear on the Harry Potter reunion special where other stars came together on its 20th anniversary. Rowling wrote, “I spoke up about the importance of sex and have been paying the price ever since.”

What is cancel culture?

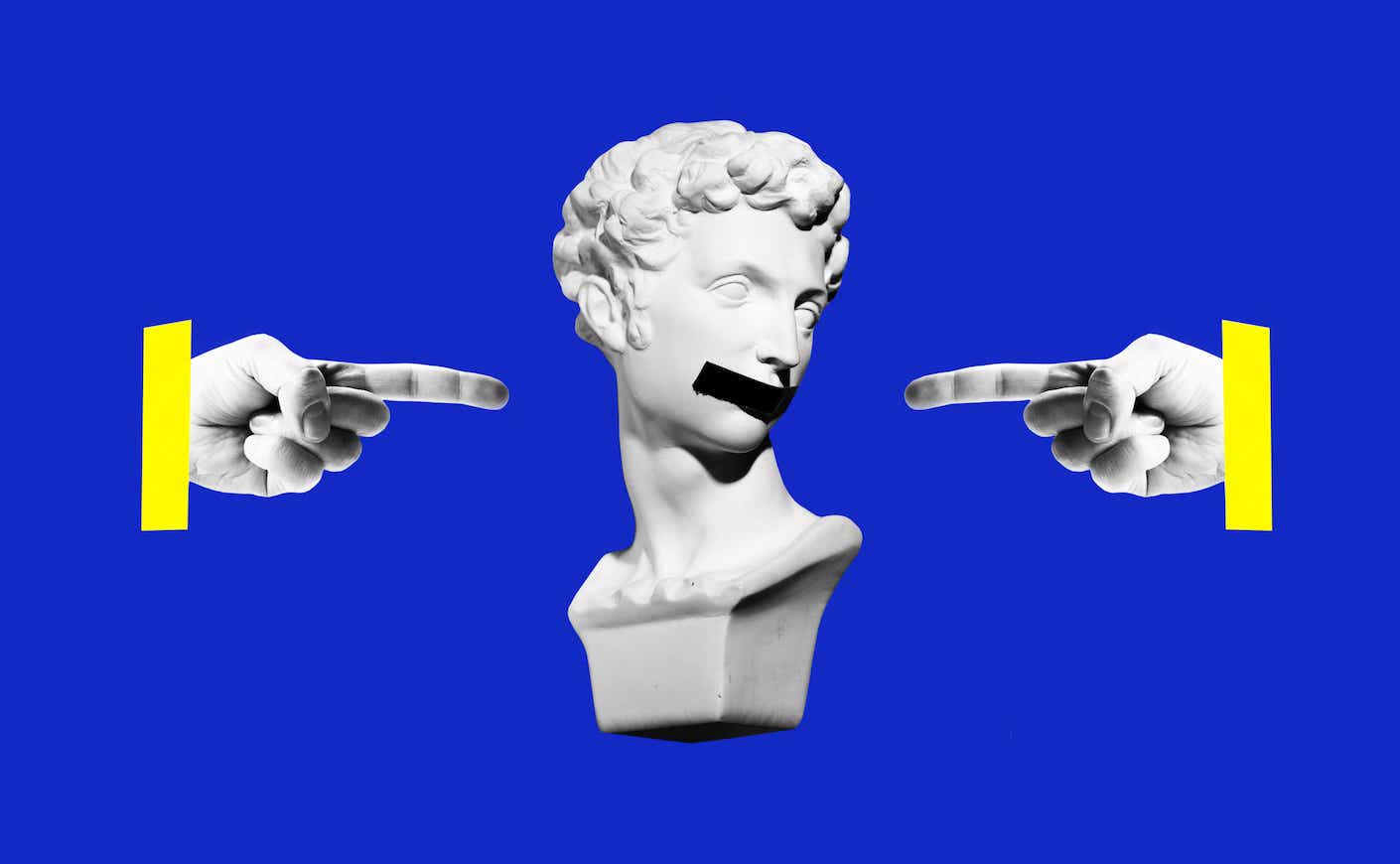

Even as tales of cancel culture fill newspapers and social media feeds, disagreement on its definition and impact continue. Some consider cancel culture an important tool for accountability and social justice. Internet culture reporter Aja Romano explains this perspective as “a way of combating, through collective action, some of the huge power imbalances that often exist between public figures with far-reaching platforms and audiences, and the people and communities their words and actions may harm.” Meanwhile, critics of the trend view it as the rule of merciless internet mobs.

Alternatives to canceling people are seen in the concepts of calling-out and calling-in. While the former is understood as “publicly shaming another person for behavior deemed unacceptable,” calling-in is about pointing out issues privately, with respect and compassion.

But cancel culture isn’t just about public shaming; it’s about lasting professional consequences, or at least that’s usually the intent. Public shaming is followed by “calls to cancel the person” — to smirch their career and oust them from society. Calls for cancellation originating on social media don’t always stick, but they can lead to firings, resignations, and lasting emotional and mental trauma for those targeted.

When did cancel culture originate?

Google searches for the term “cancel culture” began to bubble up in mid-2019, peaking in July 2020 — right after former President Donald Trump denounced the phenomenon. That was followed by a letter published in Harper’s Magazine condemning the stifling of dissent, which was signed by more than 100 renowned journalists and thought leaders, including Noam Chomsky and Malcolm Gladwell. But the seemingly modern process of “cancellation” pre-dates social media, where it’s often said to dominate the conversation. The term originated from the 1991 film New Jack City and, years later, was widely used by Black thinkers and comedians on Twitter in the mid-2010s as a way to — seriously or jokingly — disapprove of another person’s comments or actions. And the concept of social ostracism clearly goes back to the earliest forms of society. (Cavemen were likely shunning each other for trangressions long before language existed.)

Why you should care about cancel culture

This phenomenon has had a significant impact on not just individuals, but on our discourse — and has even impacted societal norms.

Many of cancel culture’s “victims” are public figures who’ve suffered professional consequences as a result of the calls for cancellation. The list includes Alexi McCammond (who lost the chance to serve as the editor of Teen Vogue after controversial decade-old tweets were discovered on her account), Mike Richards (who had to give up his role at Jeopardy! after offensive comments he’d made on a podcast were resurfaced), Billy Bush (who lost his show at NBC after tape was released of him joking with President Trump about sexual assault), Chrissy Teigen (who stepped away from her brand due to offensive tweets), and Aziz Ansari (who spent time away from his comedy tours and shows after being accused in January 2018 of sexual coercion by a woman he’d dated).

But the impact of cancellation goes beyond a person’s career: Mental health and wellbeing coach Lily Silverton explains that although ostracism is not a new practice, social media has created a “particularly virulent form of mob justice that is degrading our (already taxed) mental health.” In fact, comedian Aziz Ansari described his experience following calls for cancellation by comparing the feeling to death: “I saw the world where I don’t ever get to do this [comedy shows] again. And it almost felt like I’d died. In a way I did.”

It’s worth pointing out that while the consequences of cancellation may feel all-consuming, many of those who’ve experienced it continue to thrive professionally afterward. Billy Bush is now the host of Extra, McCammond is now a successful political journalist, Chrissy Teigen continues to bring in lucrative partnerships for her brands, and Aziz Ansari resumed doing stand-up five months after those sexual-coercion accusations surfaced. And though to some, J.K. Rowling might’ve seemed canceled for her anti-trans comments, the numbers paint a different picture: Her book sales saw a significant increase in 2021-22, when she sold 3.29 million copies in the United States — a 9.3 percent jump from the previous year. The books, movies, and theme parks inspired by her work continue to thrive.

Cancellation can also manifest in broad cultural ways, like the banning of The New York Times Magazine’s The 1619 Project, which works to reframe the nation’s history by keeping the consequences of slavery and the contributions of Black Americans at the center. It’s also resulted in the high-profile banning of other books, of course. And while many of the modern cancellation tales that make it to the news revolve around celebrities or public figures, plenty of non-notable people are shunned in their communities for less-visible infractions online.

Journalist and author Anne Applebaum opined on the impact of this new form of collective moral policing: “How many American manuscripts now remain in desk drawers — or unwritten altogether — because their authors fear a similarly arbitrary judgment? How much intellectual life is now stifled because of fear of what a poorly worded comment would look like if taken out of context and spread on Twitter?”

Applebaum’s concern is with lasting impact of cancel culture on society — and the potential for stifling of dissent. On both sides of the political aisle, many have argued that this tendency to cancel transgressors has hampered society’s ability to have open and constructive debates. Many thought leaders believe that this culture of stifling discussion and free speech is a particularly detrimental impact of cancel culture.

It brings up some interesting questions for self-reflection: Whether or not you believe that cancel culture has led to silencing some voices, has it altered the way you interact online? And does that bleed into how you interact IRL? Do you hold back on expressing possibly controversial thoughts or ideas for the fear of being attacked, or do you witness a marked shift in the conversations you have with your friends, family, and strangers?

Those in support of “deserved” cancellation argue that it’s given power to previously marginalized communities — offering them tools to be heard and helping shape moral standards. LeVar Burton said cancel culture has been “misnamed” and that “consequences are finally encompassing everybody in the society, whereas they haven’t been ever in this country.” Similarly, Romano says that “cancel culture” is merely a question of accountability, especially in an environment where public figures who “say or do bad things” continue to have significant influence.

If that’s the case, is targeting individuals merely a means to achieve larger cultural change? Think about the recent controversy around podcaster Joe Rogan’s use of racial slurs. While Rogan lay at the center of this debate, the general discussion turned into a broader interrogation around the use of such terms in and out of context, as seen in articles in CNN and the New York Times. (And as for long-lasting consequences, Rogan hasn’t experienced many — he received a $200 million deal with Spotify for his podcast, which still attracts nearly 11 million listeners per episode.)

In the end, the impacts of cancel culture aren’t mutually exclusive — a cancellation could simultaneously hold people accountable and lead to trauma for an individual. However, in a polarized political environment, critics often place these impacts at odds instead of in parallel with each other. That’s a shame, since cancellation often leads not to silence, but to reinvigorated conversations about what we hold dear as a society — and what we will and won’t accept.