Last week, I was lucky to be invited to the opening night of a new play, Power of Sail. What, you might be thinking, is the title's meaning? I’m not entirely sure, but more on that in a moment...

For most of us, it’s been a while since we went to a theater or a live performance. Other than Katie’s Going There book tour last November, it’d been almost two years for us. But it was a pleasure to be back: As the announcer over the PA said to the audience at LA’s Geffen Playhouse — after asking us to make sure our cell phones were silenced — “Welcome home”! You could sense that the audience was pumped to see the show. Before arriving, I didn’t know anything about the play other than it featured Bryan Cranston. That was more than enough to get me to the theater (rapid test, ID, and mask required).

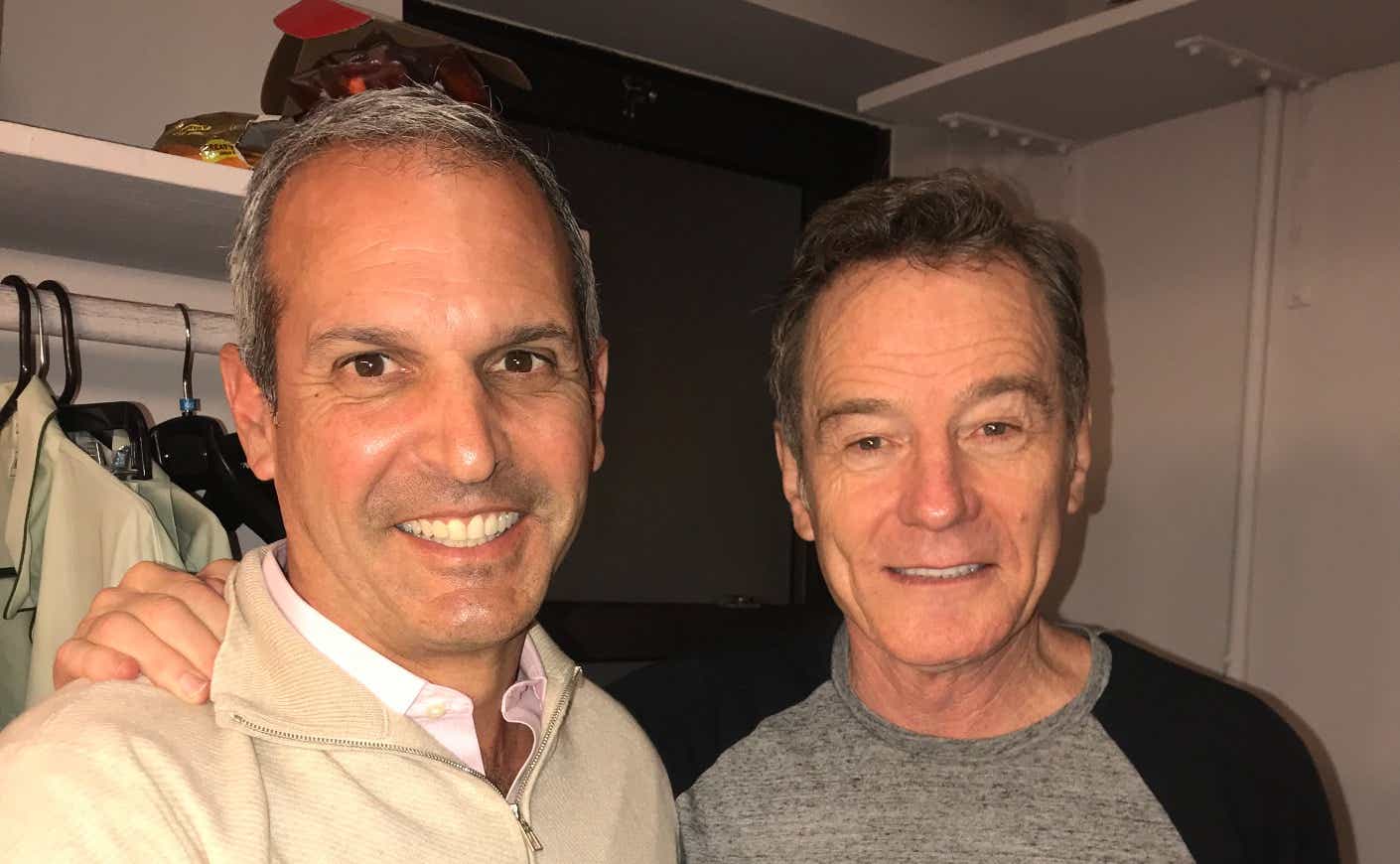

I’m a huge Cranston fan. Breaking Bad (along with The Sopranos) is my pick for best TV series of all time. Walter White simply couldn't have been played by anyone else. But he’s been wonderful in roles large and small — from the wacky, nitrous oxide-inhaling dentist Tim Whatley on Seinfeld to a judge entangled with the mob in Your Honor. He’s also starred in memorable Broadway shows including LBJ and Network. And his recent memoir, A Life in Parts, shares stories from his unexpected career that — despite what many Breaking Bad fans might believe — was anything but an overnight success. I gulped it down.

His new play — as Cranston shared with me in an email — “ is very prescient… even more so now than when it was first written in 2016.” Cranston plays Charles Nichols, the embodiment of White privilege (he’s fifth-generation Harvard). Nichols is a respected and long-tenured professor whose influence is declining while other progressive (and diverse) voices are becoming more prominent. Against forces of change, what is Nichols willing to do to maintain his position of authority and relevance?

Without giving too much away, controversy erupts when Nichols insists on bringing a White Supremacist speaker to campus. Nichols defends his decision by positioning himself as a free speech absolutist. Students hold protests to express their anger, seeing no value in giving hate a platform at Harvard.

As Cranston’s character says, “I’m the good guy, he’s the bad guy.” For Nichols, the only way to prevail over evil is to shine a light on the argument. His real intentions — and the deal he made with the proverbial devil come into focus as we learn why Nichols rationalizes his decision to include a toxic figure in his respected speakers' symposium. How far will the students go to force Nichols to disinvite the speaker? When does free speech become hate speech? Are repugnant views reason enough to deny someone the ability to express them? And who decides? Can immoral — even illegal — actions be justified if carried out in defense of a moral cause?

Power of Sail refers, in maritime terms, to the right-of-way: A powerboat always yields to a sailboat. I don’t know for sure what playwright Paul Grellong meant here, but we’re at a point in our own society where established power (privilege) is being pushed to yield rights to others. For many, this change is long overdue. Others see it as a threat, and resist to protect their status and self-interest.

Democracy only functions if we follow the rule of law. What happens when we can’t agree on what’s right and what’s wrong?

We see ourselves as moral, but in the face of evil, what actions are justifiable? Power of Sail puts this issue front and center. We are the good guys — right?