Belgium, the late 1940s: My grandfather, Aaron, newly liberated from Auschwitz, falls in love with my grandmother, who’d been a resistance fighter in Germany. They decided to go back to his hometown of Antwerp, a port city famous for the centuries-old Diamond District. Several times a week, my grandfather travels to the municipal offices in Brussels looking, praying, for any kind of notification that somehow, some of his other family members have survived. Maybe one of his sisters was young enough, healthy enough to make it out — he couldn’t imagine he was the only one. And yet, he was.

Between 1942 and 1945, more than 25,000 Jews were sent to their death from Belgium, including my family from Antwerp. Approximately 1200 survived — all my ancestors, gone. Except my grandfather, who was left alone to try and rebuild, shouldering the crippling pain of loss and sorrow. Since my grandmother knew how to sew, and he had an eye for fashion, the two decided to try their hand in the fur business. He slowly built his shop on fur coats and Shtreimels, the large fur hats worn by some Ashkenazi men on Shabbat, holidays, and other festive occasions.

They were successful, my grandparents. The house I grew up in was a happy one, and open to discussions around all but around one topic: The war. The fear and panic around that subject hovered in the background, like an endless hum.

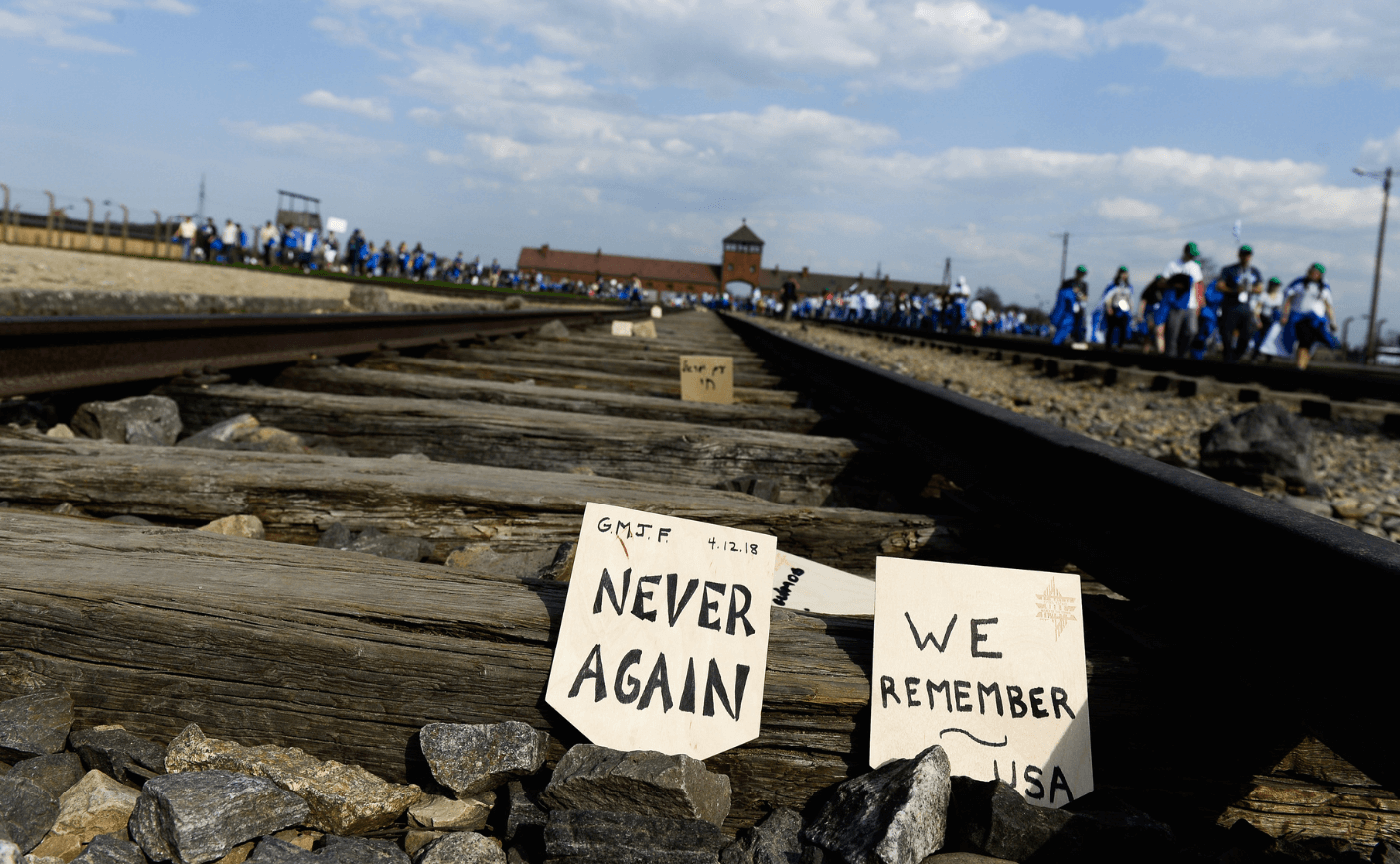

The specter of the Holocaust still looms large, not just in Jewish households like mine, but in the homes of all those who fought against Nazism and the attempts to impose a regime of fear and white supremacy. And perhaps because that fight was successful, and Israel was established, and we chanted “Never Again,” we believed the same thing couldn’t or wouldn’t happen ever again. But here we are. Again.

It’s 2022, and antisemitism is not only alive, but has seemingly flooded every platform and screen, releasing a venomous stream of poison into the body politic. And for the first time in my lifetime, I’m legitimately afraid.

Kanye and Kyrie Irving are just the latest racist celebrities to spew antisemitism, but there have been plenty more. Some have been more subtle with their remarks, and others much more blatant: In early November, the FBI issued a credible warning of threats to Jewish centers and worship sites in New Jersey. Because of the persistence of antisemitism, synagogues often have security guards, something you rarely find at Christian institutions. Now those guards are armed.

In the past, I asked my grandparents: Did you not see the persecution coming? Why didn’t you leave? After all, antisemitism was rampant long before the Holocaust. “The death toll and destruction wasn’t predictable then,” they said. “We thought it would pass. We thought it was just words.” And here we are again, hearing the drumbeat of hatred growing louder.

Echoes of 1930s Berlin, then the epicenter of culture in Europe, haunt me. The slow process of vilifying the Jewish people is what made the Holocaust possible: First hate speech, then violence, then expelling Jewish lawyers and judges from the courthouse in Breslau in March of 1933. Little by little, Jews were systematically made unequal.

Antisemitism cohabitates with racism, intolerance, ignorance, violence, and ultimately the erasure of minorities and vulnerable populations. To me, it’s the proverbial canary in the coalmine, alerting us that the very fabric of our culture and society is in danger, and that bloodshed is soon to come.

Equality and the defense of all people is a lesson that humankind seemingly refuses to learn: A sneaker company has to be consistently publicly pressured to cut ties with those who express blatant hate. And yes, those of us watching in fear cling to every supportive Instagram post by a celebrity, but those can be performative acts. Battling antisemitism has to be about more than that: It should be part of our country’s core values.

After all we’ve done to make American society a better place for people of all creeds, ethnicities, genders, or sexual ordinations, Jewish hatred is tolerated with relative ease. Aside from my fear, I feel alone — so many of our so-called allies are silent. Again.

But it is not just allies who are silent. Many jews are complacent, feeling it doesn’t affect them. But another motivation is fear: The fear of retribution, of being isolated, of being seen as a member of a persecuted class. Or perhaps it’s guilt — guilt that Jews feel for the success they enjoyed after the war. Many (not all) have done well, maybe even disproportionately well. Is our collective guilt keeping us silent? Are we afraid for not just surviving a regime that tried to completely eradicate us, but for thriving in the aftermath?

Jewish mystical tradition teaches us that we’re all interconnected; the phrase “Arevim ze laze” translates to “All are responsible for each other.” That means that every action we take, or refrain from, affects the whole community. We must choose connection at all costs.

Our silence as Jews means that we’re not willing to stand up for what is right. Silence means that we’re not willing to learn from history and do better. Silence means that we are not invested in creating a better world for our children. It means that we are complicit in the erasure of human dignity. It means that we are still choosing to pretend that this isn’t serious, and that we’re not complicit.

In practical terms, silence means that you agree and support antisemitism — that you don’t see value in fighting it and that you don’t recognize how it affects us all. It means that you’re choosing to ignore history and its lessons and as the old adage says, dooming us to repeat it. My grandfather’s sisters didn’t get the chance to fight and protest. I do.

Rabbi Igael “Iggy” Gurin-Malous is the founding rabbi and CEO of T’shuvah Center, an intentional spiritual community of healing in NYC. He is a renown Talmud teacher, spiritual counselor, artist, and educator who’s often called upon to speak and write about modern spirituality, Talmud, Jewish text, addiction, recovery, fatherhood, and LGBTQIA+ issues.