My father wrote the book You Can Negotiate Anything when I was twelve. Before that, he’d been an expert in the field. He worked for the Justice Department, CIA and several presidential administrations. He taught SWAT commanders how to talk to terrorists in hostage situations. He helped create the FBI’s famed behavioral sciences unit, because, as he liked to say, “to understand the price, you have to understand the player.”

He did not write his book in a normal way but instead announced his intention to “put all this stuff in a book,” went down to our unfinished basement, a basement that flooded whenever it rained, and stayed down there for months. We remembered his existence only when he called up to my mom, “Ellen! More coffee!”

When he emerged at the end of summer, he carried a sheath of coffee-stained pages — he’d written the book longhand, on yellow legal pads, in calligraphy pen. He held the pages before us as Moses held the tablets before the ancient Hebrews. He did not say, "BEHOLD!," but might as well have.

My mom typed it up and sent it to every publisher she could name: 23 submissions, 23 rejections. As James Thurber said of his own early work, “They came back faster than ping pong balls.”

When my father finally found a publisher to print the book between hardcovers, he went on the road and sold it from the trunk of our station wagon, like a record man breaking early rock n' roll.

The book found its audience not just with business executives, but with regular people: Because it was written in his voice, which came from that part of Brooklyn where they say "turlet" for toilet; because it was funny and human and because it took an activity people feared — negotiating — and brought it down to earth. Not by saying “You can learn to do this,” but by saying, “You don’t have to learn because you’re already been doing it every day, even if you don’t know it.”

To make this point, he opened the book with me, at age 9, having a fit at a restaurant in Northbrook, IL, called Henrici’s, thus getting what I wanted — to be taken home; I hated eating out — proving that I was a natural negotiator.

His book began showing up on local best sellers lists in the Spring of 1981, then on regional lists, then, finally, on the New York Times list, which, to him, New York born and raised, was akin to the Golden book.

My father always believed too much success is an even bigger disaster than too little, which probably made it a good thing that he never got to live his entire dream — being number one in the New York Times. No matter how high he climbed, he simply could not unseat Cosmos by Carl Sagan, which occupied the top spot like an anchor.

To this day, I can’t look at the night sky without a twinge of resentment.

To me, the most amazing fact, as a kid and adult reader of You Can Negotiate Anything, is the nature of his research. Most of his lessons, which he taught via aphorism — “the secret is to care but not that much,” “power is based on perception; if you think you got it, you got it, even if you don’t got it” – came not from books or board rooms or even from his early career as an Allstate claims adjuster. It came from his childhood adventures in Brooklyn in the 1950s and 60s, where, as part of a gang called the Warriors, he led various soon to be Bensonhurst legends, such as Larry King and Sandy Koufax, into and out of every kind of jam-up. (Google “The Moppo” or “Caravel” story for lots more on that.)

There was always an element of fun when my father did a deal. Whether talking nuclear proliferation with the Russians or the blemish on the floor model with the salesperson at Sears, he approached it like a game. And it was this attitude, and the worldview underneath it, that I want to thank him for on Father’s Day.

It was my father who popularized the term "win-win." Because that's what he taught and that's what he believed: That conflict resolution, deal-making, relationships — none of it should be zero sum, meaning for me to win you must lose. "Infinite sum" is a better term for what he was after: For me to win, to truly win, my opponent has to win too. Otherwise, what seems like a victory will merely sow the seeds of the next conflict.

And he didn't just take that approach in business. It was true to him in family, friendship, and every kind of relationship. It was his philosophy for everything. That’s what he was teaching me when he talked negotiating. “It’s not just about the car,” he said when I closed the deal on my first car, a used 1984 Dodge Daytona. “It’s about life.”

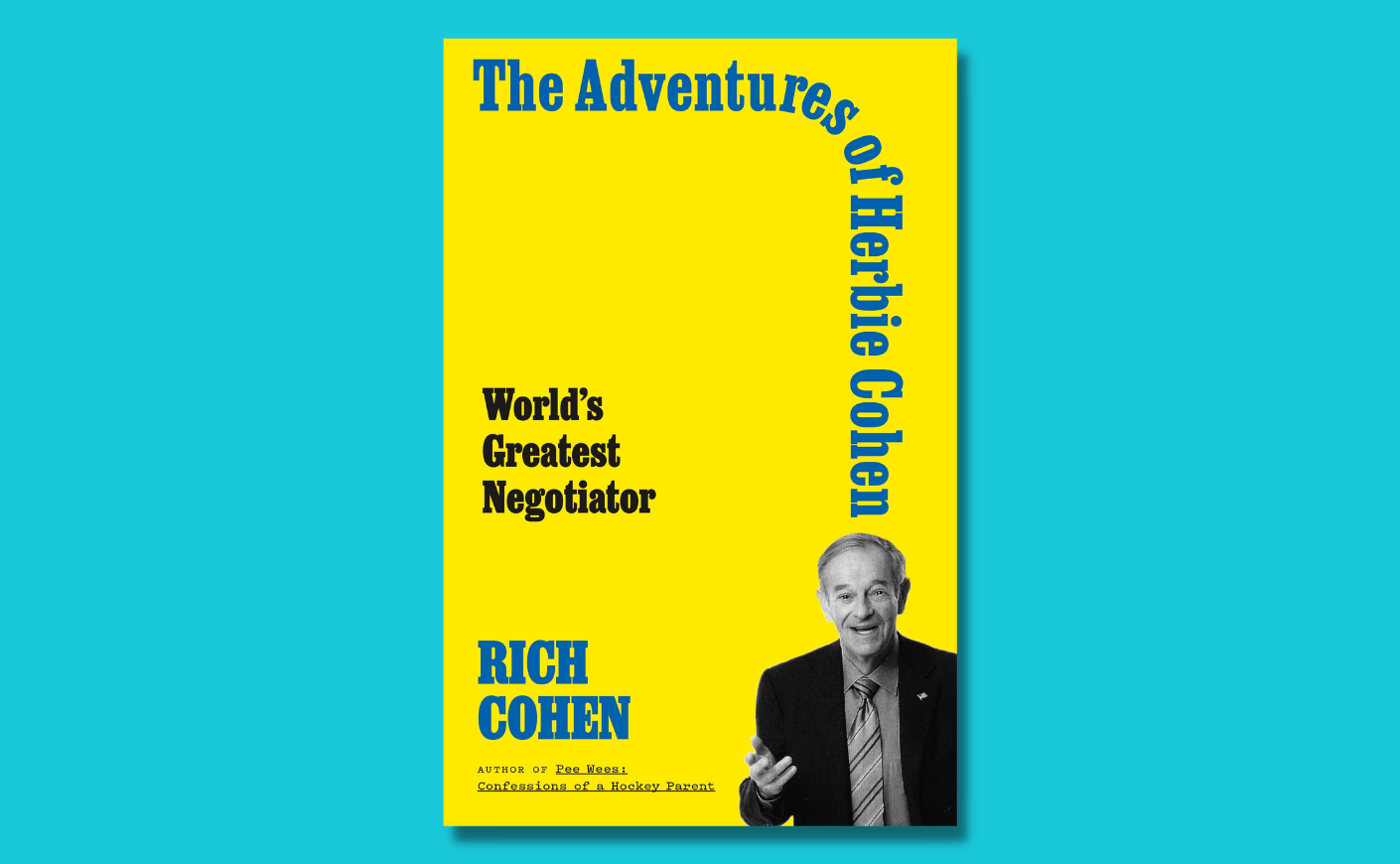

Rich Cohen is the author of several books, including the new biography The Adventures of Herbie Cohen: World's Greatest Negotiator.