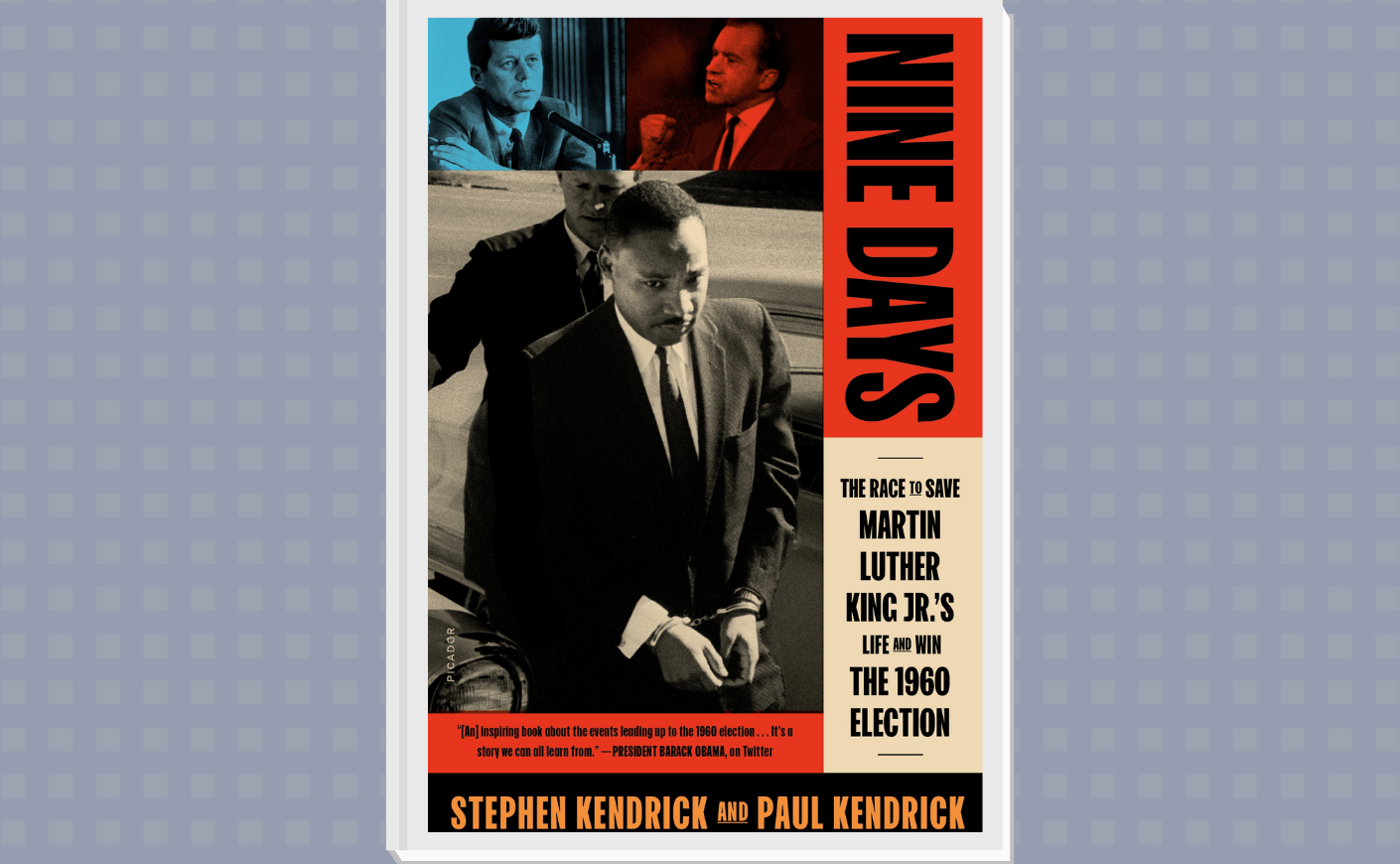

On Martin Luther King Day, it’s worth remembering what Dr. King went through to become the hero we’re honoring.

I spent a year in interviewing those who shared jail cells and late-night strategy sessions with Dr. King for my book, Nine Days: The Race to Save Martin Luther King Jr.’s Life and Win the 1960 Election. During that process I found a King who was new to me. In 1960, King was struggling to find a path towards dismantling America’s racial caste system: When the Montgomery Bus Boycott began four years earlier, he was only 26 years old. Four years later, at the age of 31, he was feeling like a one-hit-wonder — unsure of how he could advance national change, as supporters looked to him to do.

King moved home to Atlanta in 1960. At this moment, the urgency of Black college student activists propelled the civil rights movement forward with a new expression of King’s nonviolent disobedience. Students organized sit-ins at segregated lunch counters and asked to be served, waiting until they were arrested to demonstrate the absurd immorality of segregation laws. King spoke out in support of their approach, but the students challenged him to put his body on the line, too. The Atlanta Student Movement planned a sit-in for three weeks before the 1960 election where, if Dr. King joined them, it might force politicians to talk about civil rights.

King’s father begged him not to go. We’re so used to photos of civil rights leaders in jail cells that we forget what a radical and dangerous proposition it was to willingly enter a Jim Crow jail. King wrestled with the decision to leave his pregnant wife, Coretta Scott King, and his two children behind, knowing his life could end behind bars. He also didn’t know if the protest — just before a national election — was the right timing for his movement. But he decided he’d do what made him uncomfortable: He would be part of helping Americans see racial injustice as a crisis that must be prioritized by political leaders.

On October 19, 1960, King asked to be served at the Magnolia Room in Rich’s Department Store. Along with 51 brave students in downtown Atlanta that day, he was arrested. But what King didn’t understand was that, because of a minor traffic charge when he had been racially profiled months before, he was already on probation. A racist judge in neighboring DeKalb County used this pretext to separate King from the students — forcing him to face down his anxiety inof solitary confinement — and sentence him to four months hard labor at Georgia’s infamous Reidsville State Prison. King would be woken in the middle of the night, shackled, and driven away from the jail to what he thought would be his death.

Enduring that long night in the back of a police car driving across Georgia, and what he experienced in Reidsville, would be transformative. King advisor Andrew Young told me how King felt that he had been to death’s door in those harrowing days. But it was through this experience that he learned he could face down death, and jail, which he would need to do in Birmingham to change America.

Our book tells the thrilling story of how King got home from Reidsville alive, thanks to the Atlanta students, King’s family and lawyers, and an overlooked interracial team of civil rights advisors on the Kennedy campaign who used the incident to speak to Black voters and elect their candidate in a razor close election.

In writing the book, as I learned about King’s fears, he became more relatable to me — a more accessible figure than the icon I’d been accustomed to encountering in history books. On his holiday, we ought to consider how King became a monumental figure. He was a man first — understandably scared, but willing to do what his cause needed from him. This day of remembrance asks us to think of what we might be uncomfortable doing, but know is right, whether that’s speaking up against a wrong, or showing up to support a cause we believe in.

Remembering what King sacrificed for equality, we see that there is always more we can do. The holiday is not just about the hero we recognize, but the heroism we find might within ourselves.

Paul Kendrick is the co-author, along with his father Stephen, of Nine Days: The Race to Save Martin Luther King Jr.’s Life and Win the 1960 Election.