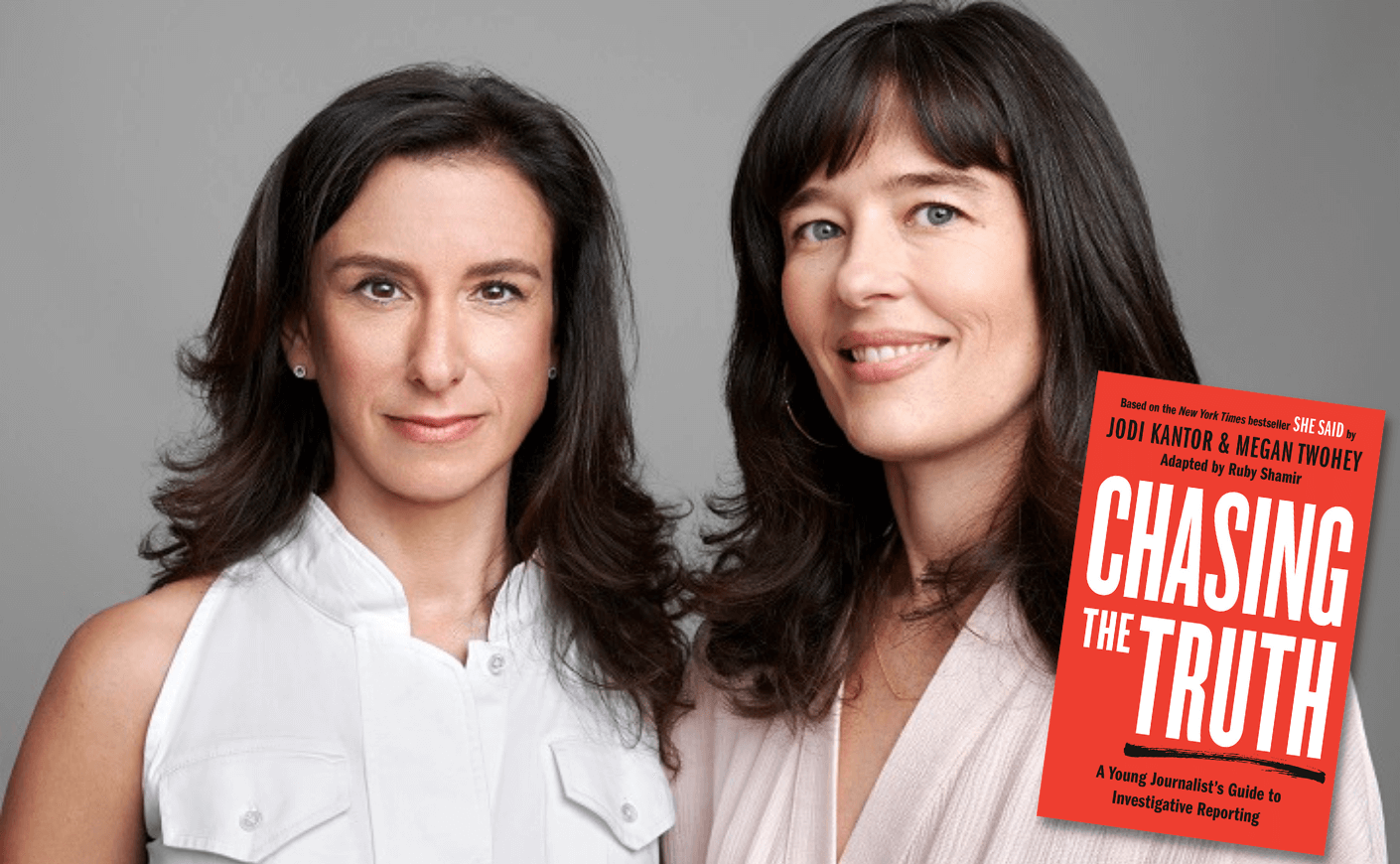

If anyone should be giving advice to aspiring journalists, it's Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey, the Pulitizer Prize-winning reporters who worked tirelessly to uncover information about Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein that eventually led to his well-deserved downfall. (And published a 2019 New York Times bestselling book, She Said, about the experience.) The work done by the pair has been culturally game-changing, and set the standard for those who'll follow in their footsteps

Now, Kantor and Twohey have laid out the best practices any fledgling reporter should be following — and why journalism matters more than ever these days — via their new book, Chasing the Truth: A Young Journalist's Guide to Investigative Reporting. Aimed at young readers and curious kids of all stripes, the book delves into how the pair of writers have cracked into meaty stories, pursued leads, and uncovered the facts. And it's a perfect entry point for the kid in your life who's always asking questions or scribbling down notes in a journal.

We caught up with Kantor to learn why this book felt so necessary right now, and how the cub reporters of today can turn into tomorrow's cultural game-changers.

Why did this book feel so vital to write at this moment?

There were so many things that Megan and I felt in the wake of the Weinstein story, but one of them was this enormous interest in journalism from young people. Part of it was a literal interest in journalism, like we saw that something really special was going on with high school and college newspapers. But we also saw the themes of journalism: asking big questions, confronting authority, holding power to account, a real pursuit of fact. We were just hearing enormous interest and enthusiasm from people in high school, people in college, people in their twenties. And we wanted to find a way to channel that and to encourage them. We're certainly trying to invite people into the profession. We wanna show young people, including young people who may not see a place for themselves in journalism, that they’re “invited” and they’re welcome.

Since the title of your book references it: What distinguishes investigative reporting from other types?

Investigative reporting is really about secrets. It's about taking information that's not "on the table" in society and putting it on the table for society to discuss. It's about penetrating some sort of closed system and finding accurate information. What happened with the Weinstein story, and then all the other great journalism that was done in the wake of the Weinstein story, is that we were able to see more. With the powerful response from women all across the globe, we were able to see that there were all sorts of things that'd happened under our noses that we collectively hadn't understood. So I’d say that investigative journalism is about teasing out secrets that wouldn't come out unless journalists really went after them. It usually involves trying to penetrate a wall of secrecy somehow.

What are some of the most important qualities for a young person to have, that'd make them good at this type of reporting?

The main thing that I think unites the kids who either want to go into journalism, or that I want to go into journalism, is curiosity. I think journalists are just interested in the world and engaged. There's a certain kind of kid who’s always asking questions. But even if you are that kind of kid, I think it can be hard to envision yourself as a journalist. When I was young, my family did have a New York Times subscription, but I didn’t know any authors or journalists. I thought that trying to go into journalism was like trying to become an actor: The likelihood of success was so improbable that it wasn't a “responsible” thing to do.

I also had an internal voice that said, Who do you think you are? And why would you presume that anybody would wanna read stories that you wrote or edited? And so with this book, we're trying to infiltrate high school classrooms, and libraries, and high school newspaper offices, especially to reach kids who aren’t necessarily well-connected and don't have easy entry points to journalism. We want to say, “This is a craft that you're gonna have to learn, and sometimes it’s really hard, but we're giving you a manual.” We also retell the story of the Weinstein investigation, including all of the juicy behind-the-scenes stuff about what really happened, and use it as kind of an anatomy of an investigation to show you what techniques we employed to ultimately break the story.

When did you realize that you were destined to become a journalist?

Oh, I was totally confused. I inhaled periodicals when I was young, but it somehow never occurred to me that I could be the one making them. I was kicked off the Columbia Spectator, my college paper, for asking too many questions. Which just goes to show that there's a lot that can go wrong in your career and you shouldn’t be daunted. And I went to law school thinking I really wanted to be a lawyer, and then I dropped out after a semester because I realized I actually wanted to be a journalist. But after being at slate magazine for a week, I was like, “These are my people, I'm home.”

What do you want young aspiring journalists to take away from this book, in terms of where to begin pursuing a story?

I’d love for young people to read this book and ask themselves the question, What would I investigate in my own community? How do things really work? Are there people around there who are getting hurt? Are there practices that need to be brought to light? Do the schools have air conditioning in the hot summers, and what's the football team doing to new members to initiate them? What are the rich kids in town doing to get into college, and are those practices transparent? Even though it's a very hard time for journalism, especially the very upsetting idea that our concept of truth seems so embattled, it's also a very good time for journalism: Right now, everybody's thinking like a journalist, because everybody knows that a lot in our society is broken.

It is a tough time for journalism, especially with the death of local newspapers and the incitements to violence against the media. Why is this career still worth pursuing? Why does it matter?

It matters so much. And whether readers of this book go into journalism or another field, what we really wanna say to them is, “You can do work that’s good and meaningful at a time when it feels like so much of the world is falling apart, and there's so much hopelessness.” What we want to say to the 14, or 16, or 18, or 20 year-olds out there is that journalism is a craft that allows you to channel those feelings into work that can really help society make progress.

Look at our story: Megan and I had no idea that this very complicated investigation we were working on in the summer of 2017 would turn out to have consequences for women around the world. We were just paying attention to craft and to detail, and doing our jobs. And you never know where that may lead.

In this book, you talk about journalistic best practices: Can you give us one that you think is ultra-important?

I think one of the things that people might find surprising is that on the one hand, Harvey Weinstein used very ugly tactics against us and our sources. He tried to smear them, he employed private spies to surveil us, he tried to hit us with a huge lawsuit. At one point, he even rushed into the building of the New York times nearly unannounced. So his behavior was really pretty bad over the course of the investigation. And yet during that entire time, we were actually trying to be fair to him. We knew that for the investigation to work, we had to give Harvey Weinstein his say. Because we knew that it would make the article stronger. And ultimately he had very little to say in his own defense.

To me, the takeaway there is: As a journalist, don't jump to any conclusions. And also, you never know where you’ll find information. One of the “Deep Throat” figures in our investigation was Harvey Weinstein's own accountant. To the outside world, he looked like a Weinstein henchman, but he became a really valuable source and he was very brave. It just goes to show that you never know where your best information will come from.

You talked earlier about how curiosity is so integral to a good journalist. Do you feel that it’s something you’re born with, or is there a way parents can nurture that quality in their children?

Megan, my partner and coauthor, talks about growing up as the daughter of journalists and how much of the family dinner-table conversation was about the news and about stories. My husband, who's also a journalist, likes to tell a story about the scientist Isidor Rabi — when he was growing up, his mother never asked, “What did you learn in school today?” She said, “Did you ask any good questions in school today?” We have a daughter who’s six and one who’s nearly 16, and we try to praise them when they ask good questions. And we try to emphasize that asking good questions is sometimes more important than knowing the answer from the outset.