The leaders of two opposing parties have settled in around me, perhaps 40 of them, along with as many others from the military and the private sector.

I’ll soon be reminding them of how the ongoing crisis has traumatized the entire country, disrupting their own and everyone else’s psychological and physical equilibrium. I’ll explain how a program of self-awareness, self-care, and group support can reverse the very real damage that trauma does to brains and bodies. I’m eager to teach them techniques that enhance mindfulness, lead to clearer thinking, and perhaps even promote compassion for members of the “other” political party.

A senior member of the Cabinet, a large, solemn man, is introducing me and the 2-day workshop. “We cannot” he begins in a resonant bass voice, “have outer peace in our country unless we have inner peace.”

I’m thrilled to hear his words, to be with leaders of opposing parties who are willing, even eager, to reevaluate long-held grudges, to consider ending the ongoing sectarian warfare and the destruction of the economy, and to work together for the good of the country.

And I’m also sad.

That’s because the workshop I’m leading is in Juba, South Sudan, and not in Washington, D.C. The man promoting inner peace is South Sudan’s Minister of Agriculture, and the people willing to explore these possibilities for trauma-healing and self-care, to create a basis for greater compassion and more effective governance, aren’t Republicans and Democrats. They’re members of the Nuer and Dinka tribes, who, even as we sit together in Juba, are still murdering one another in the countryside.

Two years later, as I speak with Dan Kildee, a U.S. Congressman who, trapped in the House Gallery, feared for his life during the January 6th attack on our Capitol, my mind drifts back to the Juba meeting. I remember that half a million South Sudanese died in seven country-destroying years of civil war and am well aware that in our own country, after only one year of COVID-19, even more are already dead.

Dan, an athletic, middle-aged, white Democrat, says that the stunned pain and suppressed anger that for weeks tightened his chest and choked his breath are subsiding. He’s been using techniques I’ve taught him over the last couple of months: slow, deep, soft-belly breathing to open his chest and quiet the fight or flight response that bodily memories of the January 6th events continue to provoke; shaking his body to melt iron bands of frozen immobility and release suppressed fear, anger, and sadness. Sleep is once again welcome and rarely interrupted; the clearing of fearful mental clutter — memories of shots fired, officers assaulted, and colleagues texting last words — is freeing him to focus on caring for himself, on attending to urgent legislation with a sharper mind, and on connecting with colleagues whose lives were also threatened on January 6th.

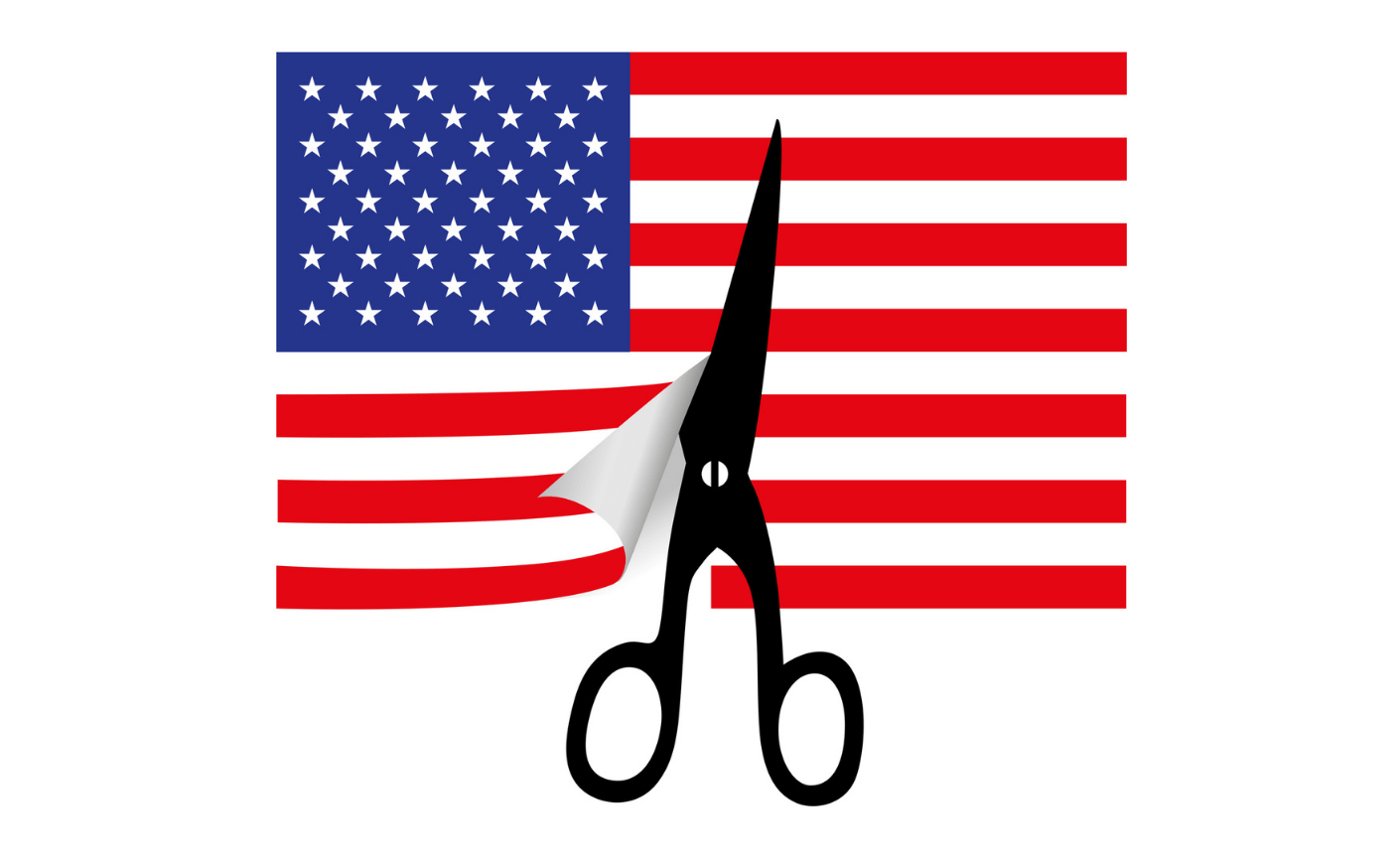

Dan Kildee is a careful listener, dedicated to the welfare of our country as well as his Michigan district, which includes the city of Flint. He’s committed to getting along with opponents as well as allies, a natural politician. He realizes that the righteous rage he’s felt will only reinforce tightly held positions — make “Stop the Steal” Republicans more defensive, confirm fellow Democrats in rigid self-justification, and perpetuate “Red Team vs. Blue Team” combat. Dan knows, too, that “moving on,” as many Republicans and some Democrats urge, is inadequate, an insult to the gravity of the insurrection and the pain that it caused. He wants to say so publicly, and is struggling to bring the authenticity that he has valued in his private life into a political world gridlocked in a bitter combat that’s sugared over with superficial courtesy.

When I tell Dan about my South Sudan experience, I recall how people with every reason to fear and hate one another — family members murdered, homes destroyed — spoke their rage and hurt, yelled and cried, and discovered, for the first time, that they shared a common suffering and a common patriotic purpose. I tell him that the cathartic storm of suppressed emotions, which I feared might send the politicians to the exits or lead to more violence, actually cleared a safe space where leaders could advance shared hopes and together commit to the future of a country that all cherished.

Dan hopes for a similar outcome here in the US. He wants to “speak [his] truth” to these Republicans and those others who support the rioters. “I want them to know that their words and actions have put me and my family at risk, that hate is dangerous to all of us. And I want them to speak their truth to me, to tell me why they think and act the way they do. My challenge,” he goes on, “is to listen to these people who are screaming for my traitorous scalp, to really hear, not deflect, their concerns — but without internalizing their hatred.”

In the months since then, other Members have been walking a similar healing path and feeling a similar resolve. They’ve been using techniques that Dan or I have shared with them, or practices they’ve cultivated on their own, to deal with the emotions that since January 6th are easily triggered: rage at Republicans who trivialize the attack, deny its dangers, and even call the insurrectionists “patriots”; fear and pain from the avalanche of social media slime and death threats directed at their spouses and children, as well as themselves; distress at a once collegial legislative atmosphere that’s now polluted with rancor and mistrust.

Congress is a place whose Members are expected to be stoical and impervious to criticism, where conversations may be, as one Democratic leader put it, “intense but not intimate.” But in the aftermath of last January 6th, legislators, particularly those who were in the House Gallery, who were most endangered by the invaders, have realized intuitively what those of us who work professionally with trauma have long understood: Reaching out to others who’ve suffered similarly, and sharing feelings openly with them decreases anxiety and brings comfort and support. These Members have been discovering strength in the vulnerability which their public posture had made it hard for them even to admit.

As the one-year anniversary of the insurrection approached, and videos of the enraged and murderous invaders became inescapable, many Members felt their fears reawakening and gratefully embraced the opportunity to share them with colleagues they had come to trust. They also tuned into the connection between the threats to their lives and the ongoing threat to American democracy, between the conspiracy-fueled rage of the rioters and the dangerous self-interest of colleagues who praise the rioters and parrot conspiracy theories they believe will please their base and guarantee reelection.

On January 6th, 2022, Dan and a number of others had the opportunity to testify to Congress and, later, on the networks, about the danger they had experienced, its ongoing destructive consequences, and the lessons they had learned. Afterward, they felt, as one of them put it, “relief and release” from the past and an appreciation of the strength they discovered in their publicly shared vulnerability, and in communicating their concerns for democracy. They were, as another member put it, “no longer victims or even survivors, but witnesses and messengers.”

Dan Kildee hopes that his own and his colleagues’ growing inner peace and their willingness to tell their truth can bring a measure of peace into the political world. He knows it is time to “stop playing the zero sum game of Red Team vs. Blue Team.” He believes that, like the South Sudanese I’d told him about, he and colleagues of both parties will be able to connect with each other as authentic human beings. He hopes they’ll find, beyond their differences, a common purpose in caring for themselves and our democracy.

James S. Gordon, MD, a psychiatrist, is the author of Transforming Trauma: The Path to Hope and Healing. A former NIMH researcher and Chair of the White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine Policy (under Presidents Clinton and G.W. Bush), he is the Founder and CEO of The Center for Mind-Body Medicine.