Chemist, emergency physician, and astronaut Anna Fisher can recall the exact second she first began dreaming of space travel: “I was inspired to become an astronaut as soon as I witnessed the first United States human spaceflight, Mercury-Redstone 3, on May 5, 1961, piloted by Alan Shepard." Fisher was 12 old. "When we got to school, our PE teacher had us all gather around to listen on a transistor radio. As we listened to Shepard talk to mission control, I decided I wanted to be an astronaut someday — but it certainly didn't seem like a very realistic goal," she tells us.

We take space travel for granted now, but when this broadcast aired to legions of captivated audiences in 1961, many Americans didn’t feel empowered to join in, since only fighter pilots could become astronauts. Women were excluded from pilot training until the 70s, so for them, space was out of reach. And even though JFK recommended selecting Black astronauts in 1961, NASA didn’t prioritize that progress for many years — which is unsurprising considering that NASA’s facilities were still segregated in the early 60s. Frankly, becoming an astronaut was only possible for white military men.

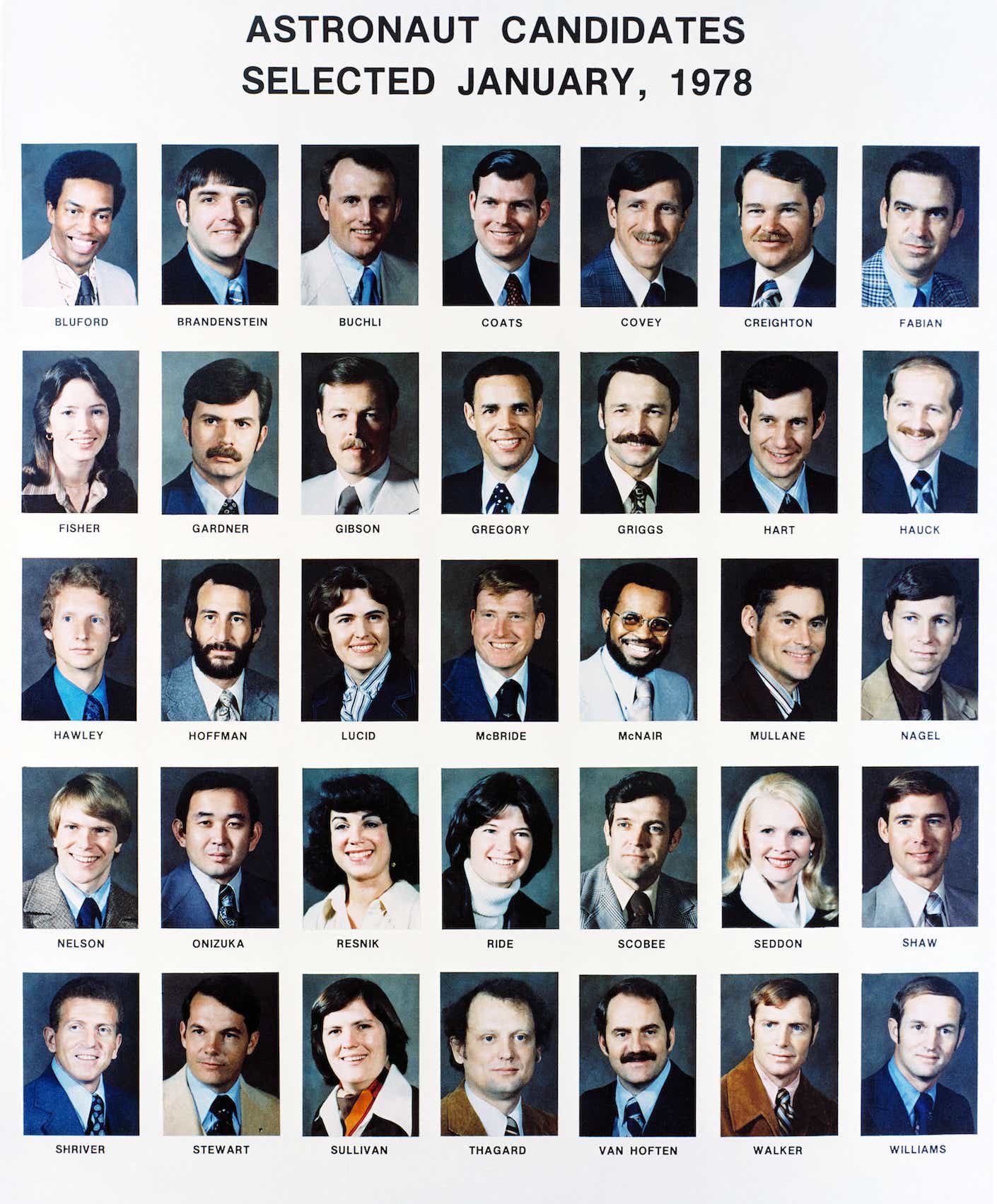

In 1978, however, Fisher and her colleague Kathy Sullivan became two of the female astronauts selected for NASA Astronaut Group 8 — the first group of astronauts to include women and people of color.

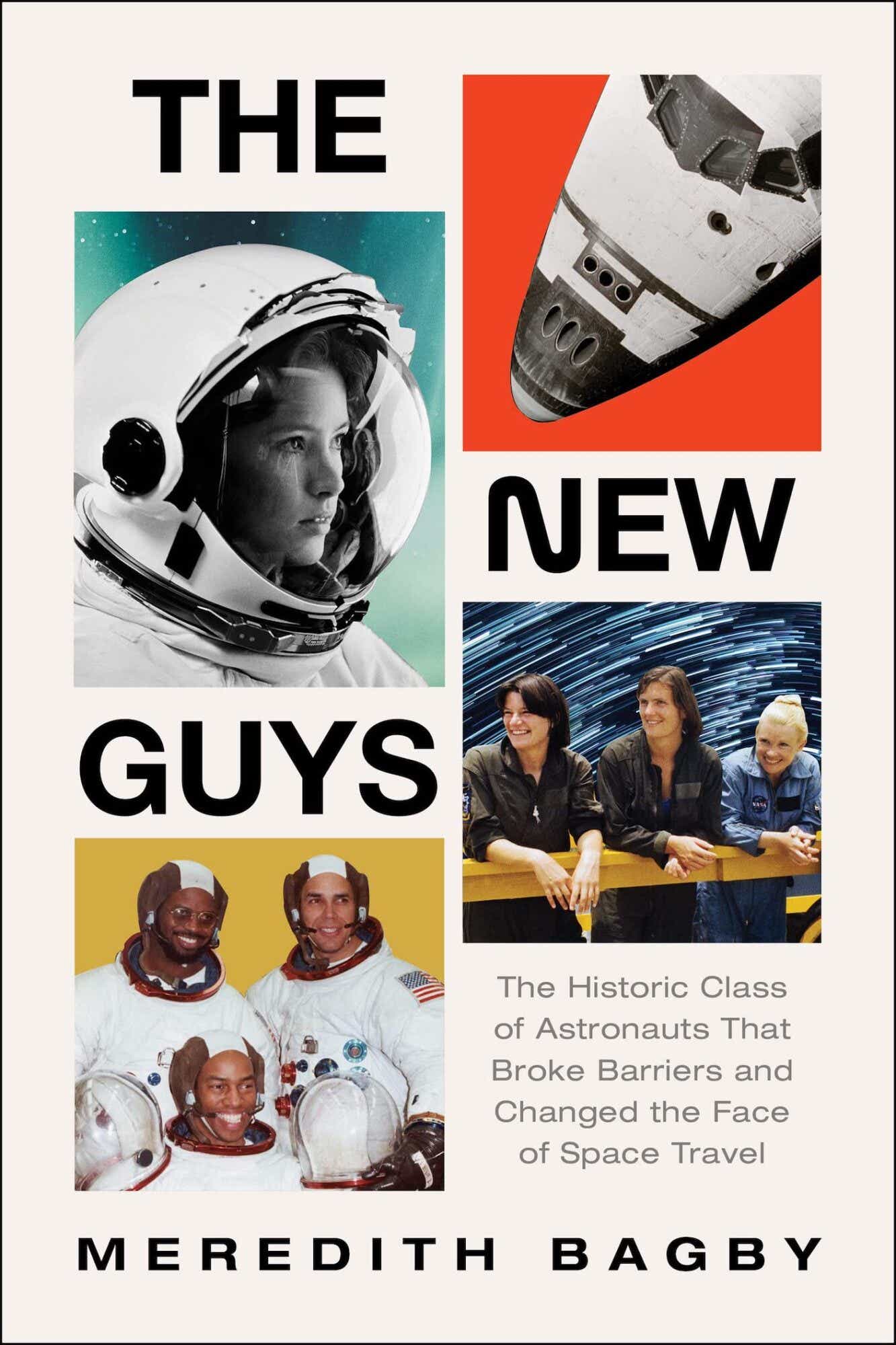

Author Meredith Bagby recently compiled their stories for her book The New Guys: The Historic Class of Astronauts That Broke Barriers and Changed the Face of Space Travel. The narrative weaves together the history of the space shuttle, the discrimination that women faced in those early years, and how these trailblazers changed the way we now perceive space travel. We spoke to all three women about how the military old guard reacted to the first female recruits, the unique prejudices they faced, and what you don’t know about how their work changed NASA for the better.

The space shuttle made progress possible

Though working at NASA seems like a lofty goal now, Bagby says that a career in space used to be much more exclusive: “Before 1978, NASA only hired white, military men who were test pilots to be part of the NASA space program,” she says.

It didn’t help that these first astronauts conformed to a cowboy-ish image, according to Bagby. “Prior to 1978, the perception of the astronaut was largely formed by the Mercury, the Gemini, and the Apollo guys,” Bagby says. Think Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landing on the moon during the Apollo 11 flight. Their adventures won the Space Race, but the historic moment became entwined with a hyper-masculine narrative that only men perform death-defying work. “They were all considered adrenaline junkies who risked their lives every day.”

Two major factors helped crack this boys club.

First, the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972 forced NASA to open its doors to women and people of color. Second, Bagby notes, the creation of the space shuttle allowed a bigger volume of astronauts to hop aboard a flight.

“[The shuttles were] much larger than any of the other spacecraft that had existed before,” Bagby says. “[Big enough to] take civilian scientists to do experiments in space.”

At the time, Fisher was knee-deep in medical training and Sullivan was getting a doctorate in oceanography. Both women dropped everything to apply to NASA.

NASA sent women to space with...strange supplies

Male NASA engineers weren’t always excellent at accommodating their new female recruits — but the organization itself had to overcome a pretty surprising learning curve in how to provide the most basic care for women.

“There’s a pretty hilarious story about Sally Ride, who was the first woman in space [in 1983],” Bagby says. “[NASA gave her] a hundred tampons that were all strung together so they wouldn't float away. She was only doing less than a week in space!”

Equally interestingly: NASA also provided Ride with an extra toiletry kit stocked with makeup — because what could be more essential to one’s survival and work in outer space than some foundation and bronzer?

Bagby also explains that NASA awkwardly approached the issue of shared living spaces between men and women. “There was concern about how women and men would operate in these small quarters by themselves,” she says, adding that NASA ended up “putting a curtain in front of the toilet.” Treating the astronauts like teenagers on an overnight school trip probably wasn’t necessary. “These folks were professionals. They were scientists.”

Considering they were scientists, these women didn’t appreciate press questions that denied this expertise. Sullivan remembers, “we all bristled at beauty queen lines of questioning coming at us. You know: ‘It was just men before, and they did all the flying, all the spacewalks, and all the science. So they don't really need you, do they?’”

Still, both Sullivan and Fisher say that they didn’t notice overt discrimination from their colleagues at NASA, but Sullivan did remember feeling tension around the differences in military training: “Most of the men in our class had probably been angling to be an astronaut for a long time,” Sullivan says. “And the definition [of that] was a very accomplished, macho test pilot, ideally with some combat experience.”

The loneliness that waits for you on the other side of a shattered glass ceiling

Women like Sullivan and Fisher are celebrated today for their roles as feminist pioneers, accelerating progress and helping create a new culture at NASA so that other women could follow more easily in their path.

What’s often not discussed, though, is how lonely this experience can be for the women who go first.

Sullivan notes that the men on her team enjoyed a camaraderie she never got to experience, simply because she was almost always the only woman in the room. “You'd have four, five, or six guys in the locker room, [which gave them time to] exchange information or get to know each other just a bit informally,” Sullivan says. “I never had that in 15 years in the program in any of those locker rooms.”

Fisher recalls a different type of isolation: As the first mother in space, she was pregnant when she was assigned to a flight.

Fisher’s colleagues were outwardly supportive of her pregnancy, she says — but she still refused to take any time off after giving birth. “Kristen was born on a Friday morning and I was at the Monday morning pilots’ meeting,” Fisher says. “I wanted to be sure that everyone knew that although I just had a baby, I definitely was going to be on that flight.”

The press was curious about motherhood at NASA, and she was saddled with reminding them that all of her male crew members were also parents. She was being alienated, in a way, even though she insists that the risks of spaceflight should be considered equally intense for a father: “I don't think it's any different for any parent, male or female.”

Looking back on their legacy — and looking forward to the future

Sullivan and Fisher insist that they weren’t planning on becoming role models when they applied to work at NASA. They were simply focused on achieving their childhood dreams and embarking on a once-in-a-lifetime adventure.

Regardless, their legacy is apparent: Contemporary classes at NASA are about half women, and NASA’s Artemis Program has committed to putting a person of color and a woman on the moon.

In terms of what makes them most excited about the future of space travel, the two women both noted what a joy it is to see women be unabashedly themselves. In the 70s, by comparison, they purposefully toned down their femininity to be taken seriously.

“One day Sally [Ride] and I went shopping,” Fisher says. “We wanted to look just like the guys — we wanted khaki pants and a shirt. The women nowadays, particularly in the astronaut office, I don't think that even enters their minds.”

She recalls standing by the elevator at NASA in recent years and overhearing two younger female astronauts debating going for a mani-pedi. It was such a simple moment, but their candor blew her away. “You can be an astronaut, but you can also be a woman in whatever way you want,” she says.

Sullivan agrees with Fisher that the progress is remarkable. “Nowadays, you can both be a full-fledged woman however you choose to express that,” she says, “ and you can also be a top-notch astronaut or any other professional.”