Nearly 20 years after the adored chef’s death, Julia Child remains a culinary and pop culture icon, and a new film explores her continuing legacy.

Directed by filmmakers Julie Cohen and Betsy West, Julia traces the late chef’s beginnings growing up in Pasadena, California and training in Paris to her rise as a celebrity chef. For those who feel they know everything there is to know about the woman, this doc has plenty of surprises in store, exploring little-known elements of her life, including her advocacy for Planned Parenthood, and her work in raising awareness around the AIDS epidemic.

One piece of advice: Don’t watch the film on an empty stomach, as it weaves in mouthwatering shots of some of Child’s signature recipes, like her beloved beef bourguignon. It also weaves in commentary on the culinary icon from fellow chefs like José Andrés, Ina Garten, and Marcus Samuelsson, along with some of Child’s own family and friends.

This isn’t the first time Cohen and West have teamed up to showcase a revolutionary woman: Their other documentary, RGB, was an Oscar nominee. The duo talked to KCM about what they chose to showcase from Child’s life and dropped some juicy hints about what they have in the works.

KCM: How did you choose which recipes to show in the film?

Julie Cohen: Probably one of the most fun parts of production was choosing the recipes — that was one of the final things we did in the film. Every recipe you watch being created is an authentic Julia Child recipe — the one exception being the vegetables in the wok that represent when Julia went to China, which was before she knew how to cook.

Betsy West: We waited to make these choices until the end of production because we wanted the dishes to kind of fit in with the narrative. So, the beef bourguignon is a classic Julia dish — yummy, sumptuous. And then we needed a dish to illustrate Julia and Paul’s life in France — their early married life, their sensuality. And when we talked to our food stylist, Susan Spungen, who’s an expert on Julia Child and was the stylist for Julie and Julia, she was the one who said, “How about the pear tart?” And she described the various steps to preparing it, which turned out to be a pretty effective way to describe Julia and Paul’s very romantic, loving, and sexual relationship in France.

Why is her relationship with Paul Child considered such a turning point for her?

Cohen: Paul Child is really who introduced Julia to the joys of food. When they met in Ceylon — which is now Sri Lanka — in the 1940s during World War II, working for the OSS [Office of Strategic Services], the precursor to the CIA, Julia was unsophisticated. She had lived a fairly privileged, but sheltered life. She was looking for adventure but didn’t really know that much about the world.

She meets Paul, a guy who’s 10 years older and is quite worldly and has a great love of culture, the arts, and food. And when they moved to France together and she decided she wanted to delve in further and start taking cooking classes at Le Cordon Bleu, he was her taste-tester and guinea pig and her most excited cheerleader.

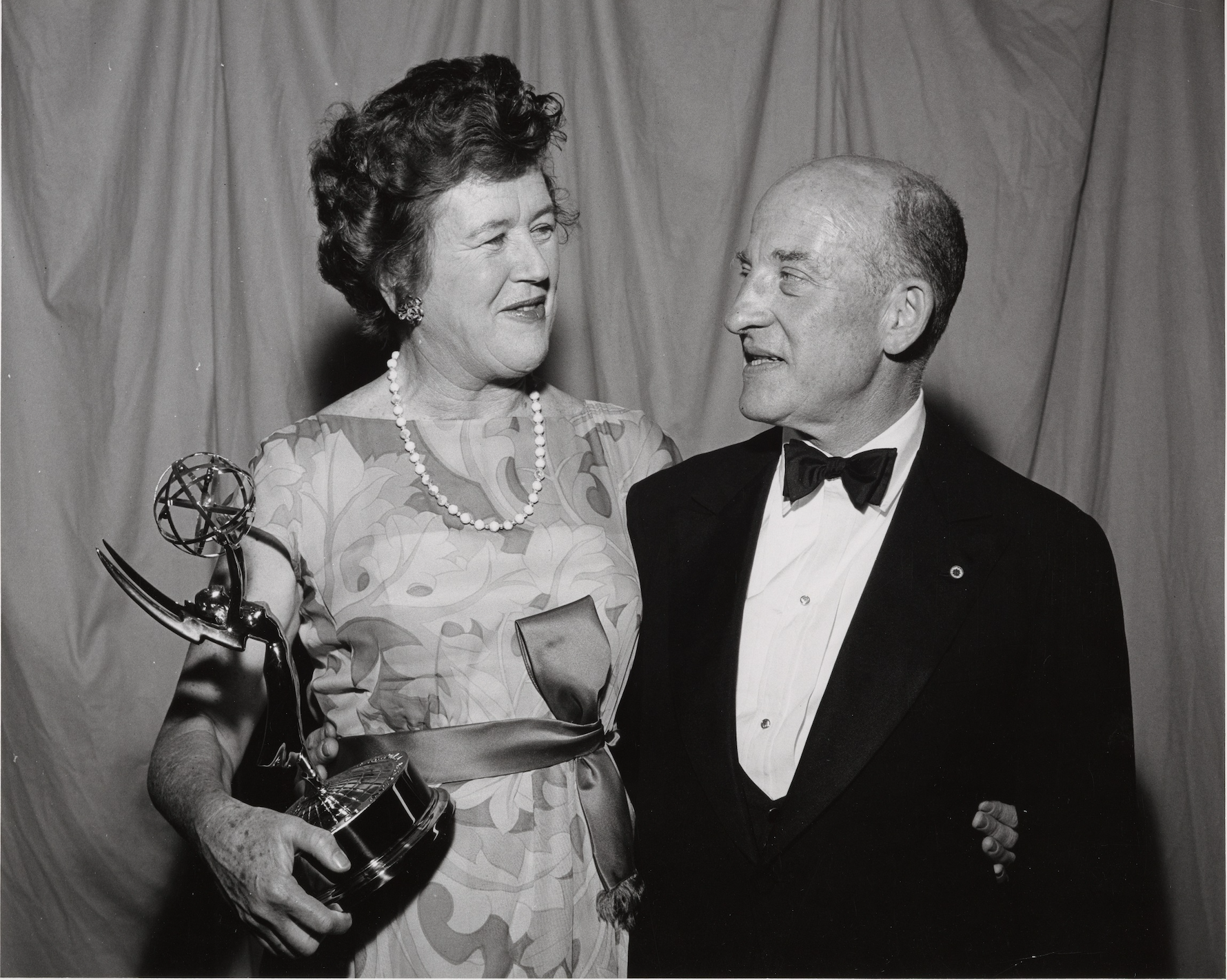

West: There are so many turning points in Julia and Paul’s story. First, Paul opens up Julia’s eyes to the world. And then Julia becomes an accomplished cook and writes this incredibly iconic cookbook, which is embraced in America. Then she goes on television and becomes a superstar. At this point, Paul’s career is in decline, but instead of being resentful or bitter about the whole thing, he devotes himself to helping Julia continue to pursue her passion.

He’s there to do everything for Julia — whether it’s helping her preparethe script or washing a few pots and pans, he’s willing to dive in. That’s very unusual for a married couple in the 1960s, for the husband to be so supportive. It really is a feminist romance and that was another thing that we just loved about Julia’s story.

This reminds me of your previous doc, RGB. Both Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Julia Child had very supportive spouses. Do you think this affected their success?

Cohen: Absolutely. Having very supportive husbands who were substantively involved in their careers was key to their successes. Just as, for centuries, loving and supportive women have been behind the careers of the great men of the world, often bringing in the brainpower to help things happen. I mean, supportive partnerships can be extremely helpful to someone’s career. That’s always been true of men. It would be more true of women if only we all had the kind of supportive husbands that Marty Ginsburg and Paul Child were.

Did Julia play a role in the women’s movement?

West: She was a role model for women — no question. First of all, she really paved the way on television for a different kind of woman to play an important role. Women on television had really been young, petite, pretty, and supportive — not the main focus of much programming. And here’s Julia Child who comes on TV, tall, a little gangly, middle-aged with a loud voice, and she’s telling people what to do, and people are eating it up. They love it. That opened up opportunities for many women on television. Similarly, Julia was very encouraging of women in the culinary field and would often go into the kitchens of restaurants and ask, as Sara Moulton told us, “Where are the women?”

Julia didn’t identify as a feminist. She wasn’t marching in the early 1970s for women’s rights. And yet she did acknowledge she was a working woman who was standing her ground. I think part of the reason [she didn’t identify as a feminist] was because of the backlash to the women’s movement in the 1980s, which is when she was being asked about all of this. At that time, feminists were supposedly humorless, bra burning, man-hating women. And Julia didn’t think of herself in that way.

But there’s no question that she stood up for women’s rights, especially in the very pivotal role she played as a celebrity putting her name out there to support Planned Parenthood and reproductive rights. You have to remember, in the 1980s celebrities weren’t attaching themselves to political causes that often. That’s something no PR consultant would’ve allowed. It was risky — something that she did because she truly believed in Planned Parenthood, and would go do cooking demonstrations in support of the organization, despite the fact that some of her fans weren’t so happy about this. Julia was a mainstream cultural icon, and had a big fan base. Some of them objected to her association with Planned Parenthood, but she shrugged that off. It was something she truly believed in.

She also eventually became vocal in supporting the LGBT community.

Cohen: Absolutely. Like so many people of her generation, Julia Child was initially homophobic, and her friends knew. It was definitely something that came up in a number of the interviews that we did with people who had known Julia in the 60s and 70s and into the 80s: that speaking derogatorily toward gays was something that she would unthinkingly do. But as with so many instances of people’s thoughts progressing and evolving, it was a personal experience that changed Julia. She had a lawyer, Bob Johnson, who became a close friend. Although Bob wasn’t openly gay, people in their circle understood that he was gay.

Ultimately, in connection with getting extremely ill with AIDS, Bob Johnson stopped lying about his identity to close friends. And Julia became a personal supporter who was by his bedside near his death. That made her think, “How are people not speaking out more about this horrible disease and its impact on gay people?” That led her to start doing benefits and talking publicly about the need for more AIDS research and support for people with AIDS. I think it’s hard for young people to understand how radical that was.

That was a period where even a lot of progressive people were not speaking publicly about the need to do more about AIDS. And Julia, with her middle America, broad political spectrum fan base, didn’t shy away from speaking out on this incredibly important issue. And that opened the door for other people to speak out. What she did was really important, and a complete 180-degree turn. We thought that also tells you something about Julia’s character.

She was also known for being very authentic. Do you think that’s why she amassed so many fans?

Cohen: Julia connected with an audience immediately. When she did her first demonstration of making an omelet on television, this very small, moribund public TV station started getting phone calls from people saying, “Who was that woman? We want to see more of her.”

I think people were really drawn to Julia’s exuberance. She seemed to be having fun and she was authentic. If she made a mistake, she acknowledged it and then showed you what to do when you make a mistake. She saw it as an opportunity. She was so relaxed and natural in front of the camera, and that continued for decades. She reinvented herself several times: First, in the 1970s, she started doing different kinds of programs when PBS tried to push her to the side. She said, “OK, I’m out of here.”

And she found herself a gig on commercial television, doing very short segments, but that wasn’t a problem for her. She just kept on learning. That’s another thing that we loved about Julia’s story. Here’s a person who doesn’t find her passion until she’s 39 years old, who doesn’t become a superstar until middle-age, and who continues evolving and wanting to stay in the game because she did love food and cooking. And I think she loved being on television and sharing her passion with other people.

As you mentioned, she was very open about making mistakes. What are some things Julia can teach us about failure?

Cohen: One of the things that her fan base loved most about her was her imperfections. There’s such a misunderstanding, especially among women, that the way you succeed is by being perfect. Everything about Julia showed that that assumption is wrong. She didn’t look perfect, didn’t speak completely smoothly — never mind the kooky voice. She also made mistakes and flubbed up and kept going. And even when she was cooking, her main area of expertise, she would screw up all the time. That was part of what made the show amusing, but also part of what made it so inspiring. We love the scene where she’s flipping the potato pancake and she’s nervous. She’s like, “Do I have the courage of my convictions to flip this over?” And as she starts to flip, the potatoes start kind of spewing all over the stovetop. And she’s like, “Well, you know what? I didn’t have the courage of my conviction, so I kinda messed it up.” And then she’s putting the little pieces of potato back and she’s like, “We’ll pour some cream in and make it seem like it was supposed to be a baked potato dish, not a potato pancake. If you’re alone in the kitchen, who’s going to see?” She made a lot of soufflés that came out perfectly, but people don’t remember those. They actually remember the screw-ups and they love them.

West: Her advice was that when your food is served, you eat it. You don’t wait for other people, or take an Instagram picture, you just dig in. But another lesson that I liked was when you work hard to make food for other people, even if you screw up a little bit or it didn’t turn out the way you wanted, when you serve it, don’t apologize.

What was it like going from Ruth Bader Ginsburg to Julia Child? How did their stories connect and how is that going to inform your next documentary?

West: When we were thinking about Julia Child, there were a couple of considerations. One is that she did have a revolutionary impact on our world and food in America. Julie and I, having grown up in the 60s, know what food was like back then. There wasn’t a Food Network. There wasn’t this obsession with good cooking. You couldn’t even find the kinds of things that you needed to cook good food back in the 60s. So here’s a person who changed the world in the same way that Ruth Bader Ginsburg changed the world. And we also thought that she was such a fun, vibrant, and engaging personality. The opportunity to dive into the cooking world, and do some of the high-end cinematography that we do of Julia’s dishes, it seemed like it’d be a lot of fun.

Cohen: And we won’t say who our next project is about, but we will tell you that it’s another amazing, strong, inspiring, phenomenal, cool woman with — not coincidentally — a spectacular feminist love story. This is actually a living woman who we’ve been filming for the past year and a half. And we’re very excited as we’ve finish up the film, and hope that it comes out sometime next year. We’ll soon be talking about who that spectacular woman is.

These women’s stories are so impressive, but they get glossed over in the media often. Why do you think that is?

West: We’ve had centuries of women being in second place. For storytellers — documentary filmmakers — in a way, it’s a great opportunity. Because these stories that’ve been, as you say, glossed over, or dismissed, or ignored, or just pushed under the rug, are really fantastic and inspiring stories. I guess we’re lucky that we’re in a time when people are open to these stories. And not just women — I think men find these stories interesting and exciting. And we’re thrilled that we can tell some of them.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.