People of a certain generation might remember where they were on August 8, 1974 — one of those moments in history that have been burnished in our brains. I was a counselor at the Columbia Lighthouse summer camp for the blind, which was on the campus of what was then Mt. Vernon Junior College in Washington, DC. There was a TV on in one of the rooms — I think it was near where some of the campers were learning braille — and I distinctly remember President Richard Nixon announcing that he was resigning.

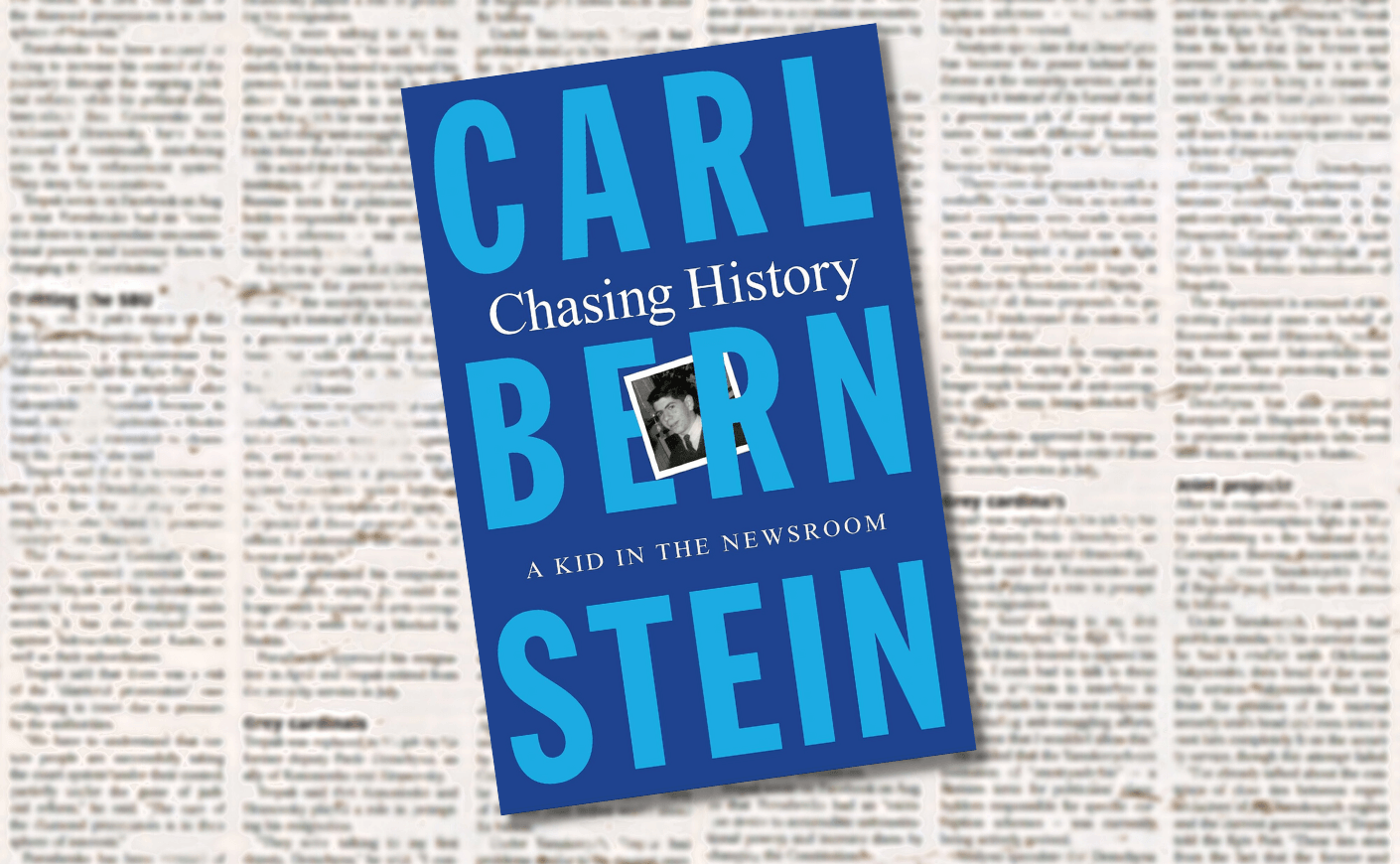

He had been implicated in the Watergate scandal — thanks in large part to the work of two intrepid reporters from The Washington Post: Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein. The two young journalists inspired many people, including me, to pursue a career in the media. When I heard Carl had written about his experiences early in his career at The Washington Star, in a book called Chasing History, I was excited to dig in — especially given the fact that since 2005, more than 2000 local U.S. print newspapers have folded, leaving 65 million Americans in so-called “news deserts.” Here’s my q&a with half of the famous Watergate duo.

Katie Couric: Chasing History is the third book you’ve written chronicling your expansive life and career. What makes this one distinctive from the others? And why did you decide to focus on the parts of your career that pre-date Watergate, that explosive, transformative story?

Carl Bernstein: The first book, All the President’s Men with Bob [Woodward], is really an account of how we covered the Watergate story at the Washington Post. There’s almost nothing in it about our outside-the-office lives, and very little about our backgrounds or biographical detail. On a basic level, it’s a detective story, about two young reporters discovering and unraveling the secrets of a criminal president and his presidency.

Whereas Loyalties, published in 1989, is a personal account of my parents’ experience during the height of the McCarthy-era witch hunts of the Cold War.

This book, Chasing History: A Kid in the Newsroom, is altogether different. It is about a spirited (and lucky) kid with one foot in the pool hall, one in the juvenile court, and barely a toe in the classroom. At age sixteen, he gets the best seat in the country, and his life is transformed by an apprenticeship at the greatest afternoon newspaper in America, the Washington Evening Star.

My five years at that paper — the rival to the Washington Post across town — were the most formative of my life. And, as only the experience of youth can be, the most joyous.

From 1960 to 1965, I learned my trade from the most talented men and women — mesmerizing and fascinating characters — who became my mentors and family. This was also a uniquely formative period in our nation’s history: The Kennedy years, the Vietnam War, the swelling civil rights movement, the Beatles. Amazingly, as a teenager, I got to cover it all, in my native city, the capital of the United States. Plus cops and cons and a slew of grisly crimes. It’s also relevant that the Washington of my youth was still a Jim Crow town: I went to legally segregated public schools in D.C. until sixth grade, when Brown V. Board of Education was decided. My five years at the Star bracketed the Civil War by exactly a century, and the pall of the War still hung over our lives.

The book ends in 1965. And yes: The single reference to “Watergate” in its pages has nothing to do with the scandal, but instead refers to a bare stretch of the Potomac riverbank where I went to military band concerts as an adolescent. Yet the unstated connection of Chasing History to the Watergate of All the President’s Men is obvious. Bob has described the reportorial education that I got at the Star as the rules “of perpetual engagement that led us to Watergate… and are to this day the touchstone of investigative reporting.”

As someone who just wrote her own memoir, I’m curious about your process…. Did you reference old diaries? Scrapbooks? Letters?

Happily, as a starting point, I had all my scrapbooks from the Star — every story I wrote there. Secondly, I interviewed almost everyone still alive with whom I’d worked closely at the paper. For context, I paged through — on microfiche — every day’s paper from 1960 to 1965. The Washingtoniana Collection of DC Public Library holds the complete contents of the Star’s library — the “morgue,” in newspaper slang — including photos and story clippings dating from the beginning of the 20th century. I combed through them for months. Perhaps most important, my time at the Star was indelible: like no other in my life, even Watergate. So I called upon my memory — but with witnesses and documents to check it against.

Chasing History takes us back to the “good old days” of journalism. What were the positive and negative aspects of the profession back then?

The positives remain the same to this day: The idea and commitment to what good reporting really is “the best obtainable version of the truth,” as Bob and I have called it for half a century. At the Star we called it “the complexity of the truth.” But to get there — and as the essential priority — it requires great perseverance; using multiple sources of information; getting outside the office to see people in their homes, away from pressure and intimidation; and always conveying the context of the story, not just disparate facts.

The downsides of journalism in that era: Too much drinking, almost as an essential element of the profession. And how resistant newspapers all over American were to hiring black reporters. At the Star, we didn’t have a black reporter on the staff until 1962. By that time, the Washington Post had hired four black reporters. Meanwhile, the number of women in American newsrooms (as opposed to those sequestered in the “Women’s department”) was conspicuously small. The Star was far better than most in this regard, with more than a dozen women reporters working in the newsroom or covering beats outside the office. Three of them were Pulitzer winners: Miriam Ottenberg, a master of investigative reporting; the great Mary McGrory; and Mary Lou Werner, a beloved mentor and a principal character in the book.

The biggest downside in today’s newsrooms? Almost all reporters today are college graduates, a disproportionate number of them from Ivy League schools, especially at the New York Times and Washington Post (including Bob Woodward, haha.) There are almost no college dropouts — like myself — working for serious news organizations in America. So a kind of elitism dominates our profession, and narrows the real-life experience and different outlooks that a newsroom should have.

You write about witnessing the intersection of print news and TV news while covering President Kennedy’s assassination. Do you think was a similar pivotal moment with mainstream media and digital/social media?

Yes. But unlike social media, the video element of TV news enhanced many aspects of our coverage, both in its truthfulness and immediacy. Social media on the other hand — unedited and un-curated by real news organizations for the most part — is more about self-expression than covering the news. As for digital transmission of real news — practiced by hundreds of news organizations descended from print newspapers — the necessity is for maintaining the highest standards of traditional reporting. Meanwhile, we shouldn’t always get too nostalgic about the past in print journalism: along with great newspapers, like the Star, there have always been lousy newspapers, lazy reporting, sensationalism, manufactured controversy, and politically “slanted” news.

Covering the Civil Rights movement was central to your journalistic journey. What has it been like for you to watch the next generation of journalists cover the post-George Floyd era?

Generally, I think the coverage today is something to be proud of, enhanced by modern technology from cell-phones to dash-cams. The real problem is where we now are as a country.

There’s so much to be learned from your story: You were scrappy and stopped at nothing on the road to success. What do you hope aspiring journalists, and people outside the industry, take away from it?

First, how important the role of the press should be, and how much fun the profession of reporting can be… Second, the importance of getting your foot in the door of something you love – and then running with it as hard as you can. Third, the role of luck, and being in the right place at the right time (i.e. the Washington Star at age 16; the Washington Post newsroom the day after the Watergate break-in) and making the most of out of whatever luck you happen into.

Trust in media is at an all-time low. Given the current ecosystem, how do you restore trust in legitimate journalism?

By doing the best job covering the news that we can. Our function as reporters and editors is not to court trust: often, the better we do at our jobs today, the more distrust we generate. We live in a culture where interest in the truth is deteriorating, and too many people (most?) are looking for information to reinforce what they already believe; to build on their already-held opinions, religious and political choices; and their prejudices. Again, our responsibility is to the best obtainable version of the truth.