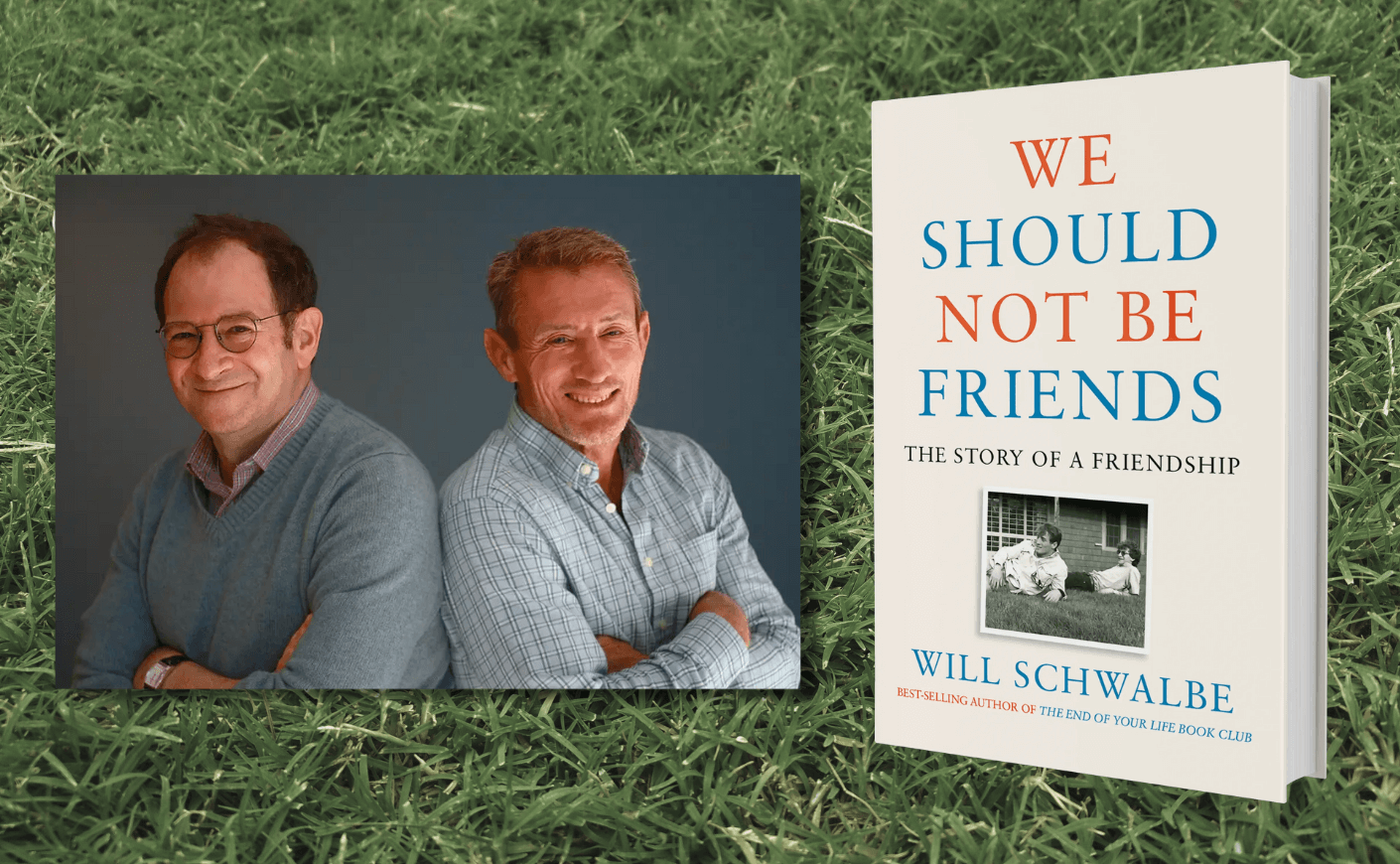

I don’t just love Will Schwalbe’s writing — I’ve considered him a close friend for 40 years now. He’s a New York-based editor, writer, and pop-culture expert extraordinaire who became friends with my older brother Tom at Yale — and they’ve remained close ever since.

Will’s first two books are both on my “favorites” list. (Katie calls me the self-appointed president of the Will Schwalbe Fan Club). His first book, the 2012 New York Times bestseller End of Your Life Book Club, told the story of his relationship with his remarkable mother, Mary Anne Schwalbe, through the books they shared together during the two years before her death from pancreatic cancer. Will followed that up with 2016’s Books for the Living, in which he told his very personal story through the lens of the books he was discovering along the way. (Will’s syllabus alone — from Stuart Little to Girl on the Train to Rebecca to Song of Solomon — is remarkable and fun; you’ll thoroughly enjoy the literary ride alongside him.)

Will’s new book We Should Not Be Friends: The Story of a Friendship explores an improbable connection he made with a classmate at Yale. Though the two couldn’t have been more different in their backgrounds and passions, the tight-knit friendship they formed has grown and endured over decades. I caught up with Will to ask about his inspirations, his thoughts on our hyper-polarized world, and what his old pal really thinks about being the subject of a book.

Why did you want to write this book, about an unexpected friendship with a college friend?

The short answer is that I wanted to help people celebrate the unexpected friendships in their own lives, especially the ones that go back years or decades. But I also wanted to convey something that I think is tremendously important in our fractured world — that we can be friends with a far wider range of people than we might think. The book tells the story of my friendship with Chris Maxey. In the early 1980s, we were both chosen for a college secret society whose purpose was to bring together the 15 most different kids and make them have dinner together twice a week for a year. Maxey was a loud, obnoxious, preppy star athlete on his way to serving in the Navy SEALs. I was a classics student, a theater kid, and an out gay activist. While it’s true he was prejudiced against me, the irony was that I was way more prejudiced against him. I made all sorts of assumptions — only to find out that I was totally wrong. Had we not been thrown together, we both would have missed out on a 40-year friendship that has changed and enriched our lives.

When did you first start thinking that this friendship was a good book? And why did you wait 40 years after that friendship started to write it?

Maxey is such an interesting and remarkable person that I wanted to write a book about him. After he served for six years with the SEALs, he went on to become a school teacher and then founded — with his wife, Pam — an extraordinary school on the island of Eleuthera, called the Island School. It changes lives. I proposed to my editor that I write a biography of Maxey; he heard me out, paused, and then said, “I think the book you really want to write is about your friendship.” He was absolutely right: That was the book I wanted to write and did.

Even if I had come to realize that years or decades earlier, though, I don’t think I could have written this book until now. Maxey and I both recently turned 60. We’ve both helped each other with illness — a brain tumor for Maxey; Small Fiber Neuropathy for me. And we are both reflecting more and more on how happy we are to be still on this earth and breathing and to have close friends, including each other. It’s a book of gratitude that reflects where we both are in our lives. It’s also, I hope, funny. The very things that used to stress us out the most now make us laugh.

What does Maxey think of your book? And what did he think of the idea when you first told him?

Right from the start, Maxey was all in. We spent hundreds of hours talking, and sharing memories with each other to help me recreate our lives as faithfully as possible. (My editor noted that the most overused phrase in the book is, “After many beers,” so it’s no wonder we needed both our brains for recall.) Right from the start, I told Maxey that he and Pam had veto power over anything and everything. I would show them the book when I was done and anything they wanted out was out, no questions asked. As far as I’m concerned, no book is more important than a friendship — so I meant it. But after they read the book, I got a call from Maxey. He said, “Don’t change a thing.” This book presents both of us warts and all. He insisted that all his warts stay. One of the amazing things about Maxey is he’s a guy who has accomplished great things, but the stories he tells about himself are usually ones where he’s screwed up. He believes you learn the most—including what really matters—from failure. We’re also going on the book tour together, which will be a riot.

You share a lot of really personal things about yourself in this book — particularly during college years but beyond, too. Did you decide early on that to tell this story the right way, you had to share very personal things?

It’s odd but I never thought not to share everything. It was only when people started reading it and telling me that I was “brave” that I thought to myself, Hmmm, I wonder if I should have shared so much… One of the true bonding experiences in the secret society is what we call the “audit.” Everyone is encouraged to do one, though not required. In an audit, you share with the others–in total confidence and in an incredibly supportive environment — every single thing you can possibly remember from your entire life. The more honest you are, the more you get out of it. I kept my original notes from when I gave my audit nearly 40 years ago, so I mentioned in the book every major thing I'd shared way back then, including things I’ve never shared before or since. It was important for me to let readers get to know me the way Maxey first got to know me, and vice versa. Having set that tone, I just continued.

I quote poet David Whyte at the start of the book. Whyte said, “All friendships of any length are based on a continued, mutual forgiveness. Without tolerance and mercy, all friendships die.” I love this — so I felt that I needed to put in the book everything for which we needed to forgive each other, and did.

Do you have other friendships in your life that you regard as both “unexpected” and important? Do you think lots of other people have them, too?

I do have several other unexpected friendships, but none where we started out anywhere near as far apart as Maxey and I were when we met. What has delighted me is finding out that many of my friends have a Maxey in their life, or a me if they are more like Maxey. But it takes effort to make this kind of friendship, and to maintain it. It was really Maxey who first reached out to me and not the other way around. Then it was thanks to a mutual friend, a major character in the book, that Maxey and I stayed in touch.

Do you think the fear of rejection is one of the big reasons we don't easily invest in relationships outside of our circles?

I think we make assumptions about others based on superficial things: how people dress, how they talk, what activities they do or don’t do, where they’re from. It’s human nature; it’s certainly easier to seek out and spend time with people who seem to be exactly like us. And, yes, fear of rejection plays a huge role in keeping us from leaving our safe zones and meeting others on neutral ground or in theirs. It’s scary to put yourself out there. But I believe that true friendship is based on shared values far more than shared interests. Ultimately, how people behave, how they treat their friends and strangers, will let you know whether to invest in a relationship, whether inside your circle or not.

In an increasingly tribal world — where we line up so strongly on different sides of issues, big and small — how can we draw together by making efforts to get to know people who are (outwardly, at least) different from us?

This keeps me up at night! I worry in particular about social media — I fear it reinforces differences, even trivial ones, especially for young people. Again, this is one of the reasons I wrote the book. But I believe that we can make a habit of getting to know people who are different from us. I read an interesting study that showed that when you let students choose their own seats in a classroom, they tend to become friends with people who are very much like them. But if you assign seats, they become friends with the other students sitting near them, whether they’re alike or not. We need to put ourselves into social and work situations with people who are different from us. If we do, we can make unlikely friendships, enrich our lives, and maybe even help save the world.