Author Jeff Nussbaum isn’t just fascinated by history-making speeches, he helped create them: He was a member of President Biden’s speechwriting team. But before starting his high-wattage position, Nussbaum finished an incredible (and just-released) book called Undelivered: The Never-Heard Speeches that Would Have Rewritten History.

In each chapter, Nussbaum examines an oration that was never given, offers fascinating peeks into (and analysis of) the original text, and recreates the fraught moment in history that resulted in the speech not making it to the public. (They include Hillary Clinton’s theoretical 2016 victory speech and one by Emperor Hirohito apologizing for WWII.) Here, we’ve got the background on an address that famed disability activist Helen Keller should have given at a 1913 women’s suffrage march — until it was broken up by 500,000 drunk male rioters.

In 1886, when Helen Keller was six years old, her parents took her from their home in Alabama to Baltimore, to see an oculist, who they thought could help restore Keller’s vision. The oculist encouraged them to visit the world-famous inventor Alexander Graham Bell, who was deeply interested in the study of speech, hearing, and voice, and was working with deaf children in Washington, D.C. It was Bell who encouraged the Kellers to visit the Perkins School for the Blind in Boston, which led to the fateful meeting with Anne Sullivan, the teacher who would change Helen Keller’s life.

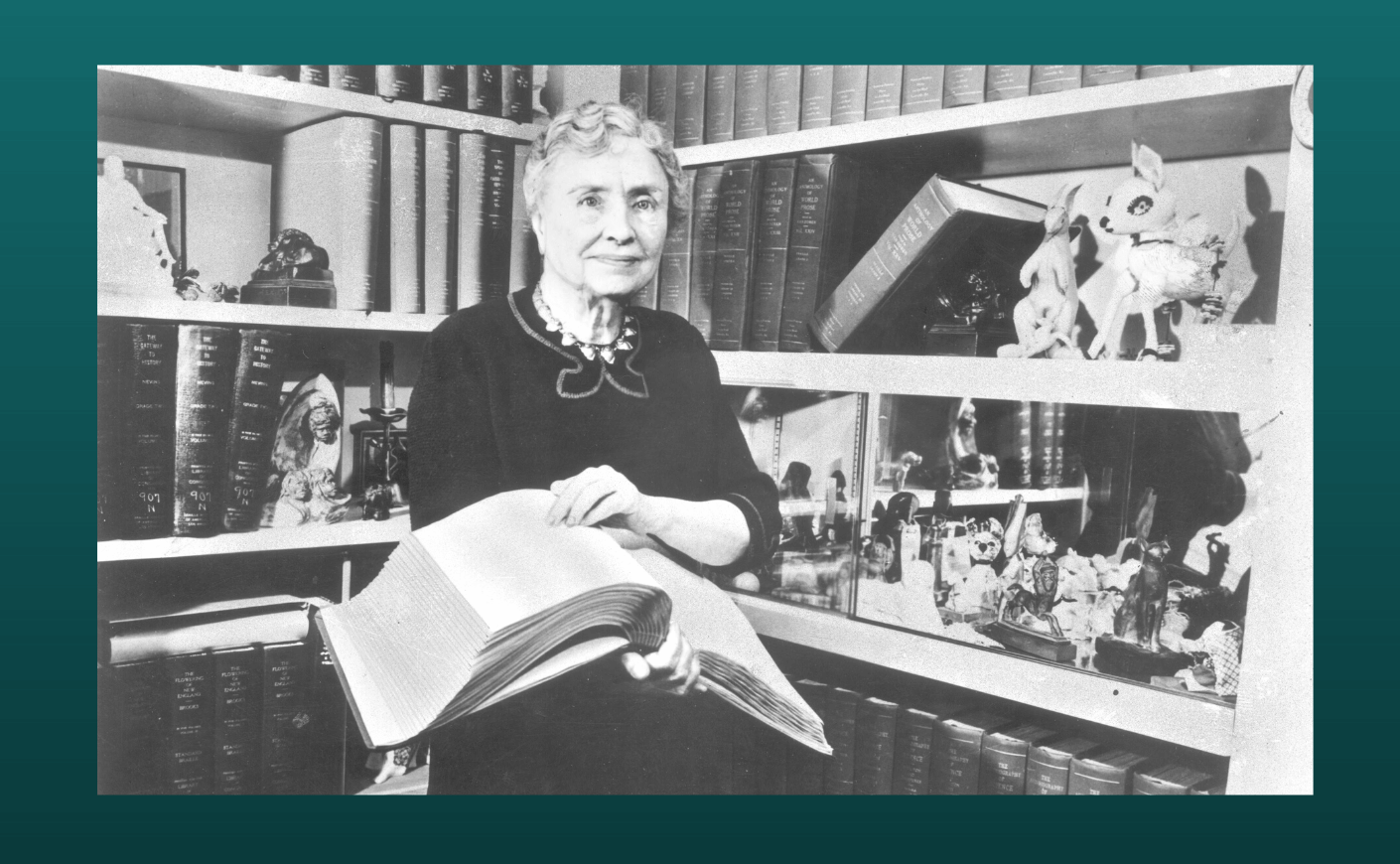

While enrolled at Radcliffe College, Keller began to write The Story of My Life, which was published in installments in The Ladies’ Home Journal. The book and subsequent speaking engagements made her famous in her own right.

But as Keller entered adulthood, she grew frustrated; everyone wanted to hear her inspirational childhood story of being rescued from the isolation of her disabilities. They were happy to hear her call for charity for the deaf and blind. But fewer wanted to hear her characterize those disabilities as civil rights issues. And fewer still wanted her to talk about her personal politics. She realized that when she spoke about her disabilities, she was referred to as brilliant, but when she talked about her political beliefs, the newspapers infantilized her, reporting that she was being “used” and didn’t fully understand what she was advocating.

In November 1912, Keller published an essay entitled “How I Became a Socialist.” And a few months after publishing the essay, she decided to speak for herself. She agreed to join a major suffragette rally in Washington, D.C., which was planned “to bring before the country in the most public manner possible the ‘nation-wide demand for an amendment to the Constitution of the United States enfranchising women.’”

The rally was to be held on March 3, 1913, the day before the inauguration of President Woodrow Wilson, to ensure that plenty of reporters would be in attendance. The hope was that Wilson would recommend equal suffrage in his inaugural address and support a constitutional amendment throughout his term,5 and the march organizers delivered Wilson a letter to that effect.

The rally began with a parade at 3:00 p.m. in front of the U.S. Capitol and marched down Pennsylvania Avenue. It was a spectacle, with all-women bands, women on horses, floats representing everything from women in the Bible to women in sweatshops, delegations from every state, and different organizations and professions in color-coordinated outfits marching behind banners.

While the afternoon timing allowed for significant press coverage, it also allowed time for a large, rowdy, drunken crowd to assemble. The five thousand marchers were soon outnumbered a hundred to one by the half-million spectators.

Almost immediately, the crowd surged in on the parade route. Marching suffragettes were reduced from one procession to small groups, where they were jeered, taunted, and physically harassed. Men tried to grab the flowers off the women’s coats or pull them down off the floats. The women had lighted cigarettes thrown at them. When one marcher had tobacco spit on her, she appealed to a nearby police officer, who responded, “There would be nothing like this if you women would stay at home.”

The Baltimore Sun reported that “Miss Helen Keller, the noted deaf and blind girl, was so exhausted and unnerved by the experience in attempting to reach a grandstand where she was to have been a guest of honor that she was unable to speak later at Continental Hall.”

And what was Keller to have said?

The speech opens with some of Keller’s most powerful lines:

I am proud to share in your brave work for the emancipation of women. From my victorious fight against the dark I bring you good cheer in your world-wide battle for light, for freedom. I am deaf; but I hear the glad tidings of woman’s liberation which shall soon be flung abroad through the land. I am blind; but I see the dawning light of a new day when there shall be no woman enslaved, no child robbed of the sweet joy of childhood in the war of daily bread. All earthly opposition cannot stay our onward march.

Keller’s well-constructed words, powerful in their own right, might have gained more power from her distinctive delivery. Keller explained that her greatest disappointment in life was that she couldn’t “speak normally.” Listening to audio of Keller, you can hear that she spoke in the distinctive diction and modulation found in those who have learned to talk without being able to hear. But an accent or unusual inflection can sometimes cause an audience to lean forward and listen more intently.

Keller may not have spoken at the rally that day, but she didn’t remain silent for long. As historian Kim Nielsen of the University of Toledo documented, Keller continued to put forward a social and political agenda, encouraging public health officials to get over their “false modesty” and educate women about venereal diseases, which, when passed from mother to baby, were one of the leading causes of blindness in the U.S. She spoke on behalf of workers’ rights and spoke out against World War I and those who profited from it. She corresponded frequently with and about Emma Goldman. In 1916, Keller wrote to the editor of The New York Call defending Goldman against imprisonment for educating women about birth control, saying, “She has consecrated her life to the salvation of the oppressed. She is now engaged in a contest with authorities of oppression. If we stand aside and allow her to be imprisoned, you and I will be imprisoned likewise.” And Goldman described hearing Keller speak at Carnegie Hall in 1916 as “one of the most stirring events in my life.”

She also continued to develop arguments for women’s suffrage. Seven months after her undelivered speech, she published an article in which she wrote that men need women’s suffrage, which includes the cheeky observation: “When women vote men will no longer be compelled to guess at their desires—and guess wrong.”

She then followed this with the more serious point: “Women will be able to protect themselves from man-made laws that are antagonistic to their interests. Some persons like to imagine that man’s chivalrous nature will constrain him to act humanely toward woman and protect her rights. Some men do protect some women. We demand that all women have the right to protect themselves and relieve man of this feudal responsibility.”

To be relieved of responsibility is also to be relieved of some measure of power and control. And perhaps that is why these—and so many other—speeches by women throughout history have been feared, stopped, and shouted down.

Women have also been stopped from speaking not because those in power couldn’t tolerate hearing their words, but because we have always understood that words can lead to actions.

Republished with permission from Flatiron Books, an imprint of Macmillan Books