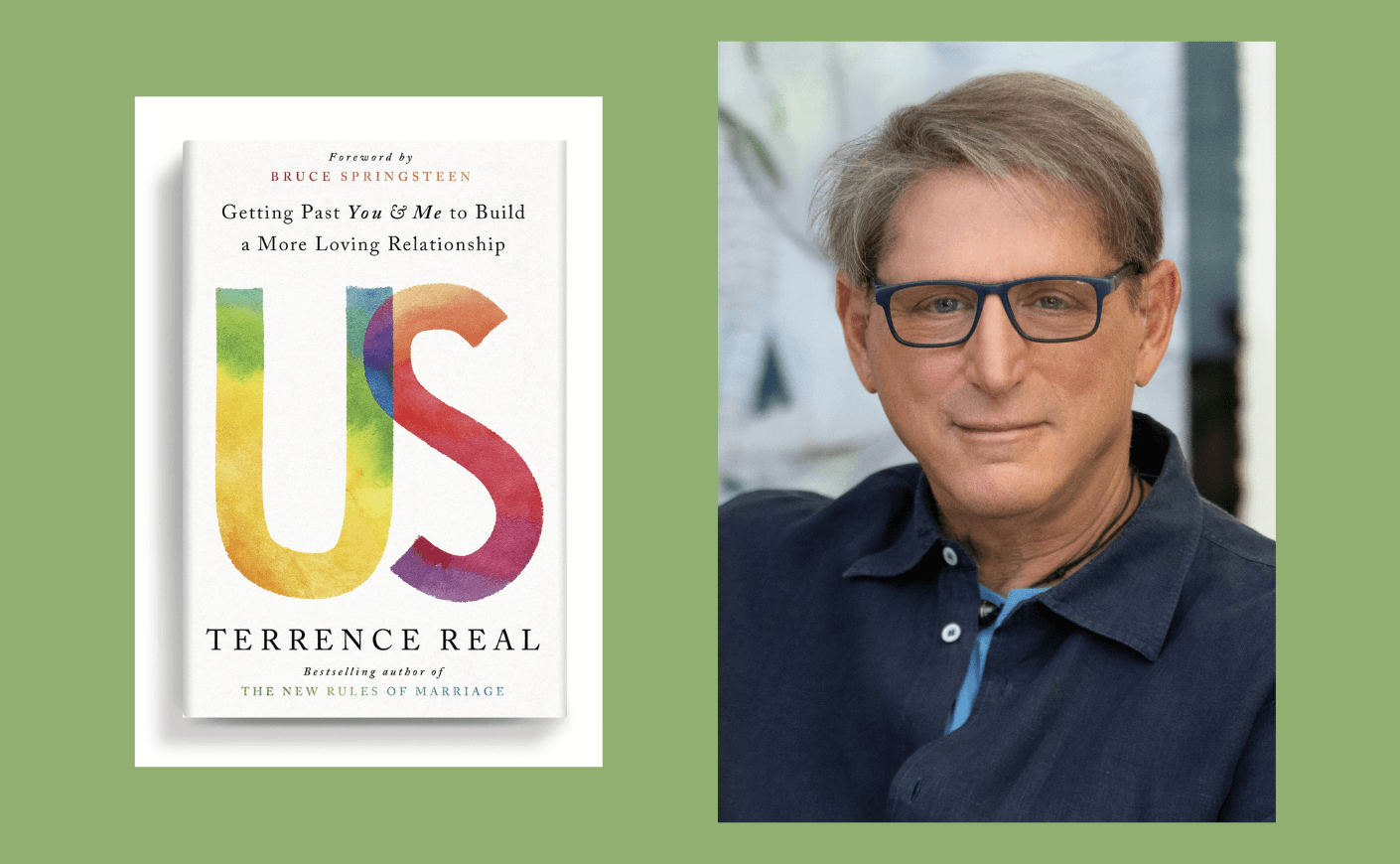

It’s cliche to say Dr. Terry Real’s new book, Us: Getting Past You and Me to Build a More Loving Relationship, changed the way I view every relationship in my life. But it’s true.

One of the pioneering experts on trauma — and generational trauma — studies, Dr. Real founded the Relational Life Institute, is a senior faculty member at the renowned Family Institute of Cambridge, and has been a therapist and teacher for over 25 years. The beauty of his work is that it’s borne of his own trauma, and of his experience overcoming that cycle.

Dr. Real and I met virtually a few months ago, while working on a project. He has an extensive, loyal following, but I wasn’t overly familiar with him, and didn’t think his work — largely focused on relationships and masculinity — applied to my life, since I’m a 25-year-old woman who has never had a serious boyfriend, and has a stellar dad. I cannot tell you how wrong I was.

His plea to see ourselves, and other people, for we all are — human — is so simple, yet so eye-opening. Terry himself is warm and calm, and every page of the book is filled with his compassionate wisdom. I haven’t devoured a book in under 24 hours in a long time, but reading this in one sitting was a pleasure.

I wanted to share everything Dr. Real has to offer with our Wake-Up Call community, so I asked him a few questions about what it means to be in a relationship with others, how to break the cycle of trauma, and why accepting love can be so hard.

Your new book is titled Us: Getting Past You and Me to Build a More Loving Relationship. First off, please explain what you mean by that title…

We live in divisive times. All around us, our sense of community has eroded. We assert our individual rights at the expense of the whole, yet we’ve never been lonelier. The same value of “me over we” invades our personal lives and does great damage to our relationships. In each of us, the autonomic nervous system — far below our conscious mind — scans our bodies four times a second, asking, “Am I safe?” If the answer is “Yes, I’m safe,” we stay seated in the mature part of our brain, the prefrontal cortex. That’s what I call the Wise Adult part of our personalities—the part that’s here and now, present-based, able to make thoughtful, smart choices. But if the answer is “No, I don’t feel safe,” that mature part of our brain shuts down, and a more primitive part of our brain and nervous system takes over.

When the mature part of the brain, the Wise Adult, shuts down because you don’t feel safe, what takes over is “you and me consciousness.” The Adaptive Child — the part of you that was formed in the absence of healthy parenting, like an immature child’s version of what an adult looks like — is not interested in intimacy; it’s interested in survival. the part of you that can remember the relationship, remember that you and your partner are a team, goes offline, and you begin to live in a “me vs. you,” win-lose, adversarial contest. Nothing will be resolved in your relationship when you inhabit that knee-jerk, automatic part of you. The essence of my book is learning the skills to shift from that knee-jerk response in the heat of the moment to the thoughtful, considered, non-traumatized part.

You’ve explained that many traditional modes of couples therapy can be sexist. Why is that, and how is your model different?

We therapists are taught not to take sides, yet across the board in the West, it is women who are carrying the dissatisfaction. It is women who are asking for more in their relationships than we as a culture raise many boys and men to deliver. I’m not neutral. Women are right: intimacy is good for us. I’m not saying that the way women are asking for intimacy is all that skilled. I’m not saying they’re angels, but what women are asking for from men is a good thing. Intimacy is good for us; it’s good for our bodies, our children, for all of us. So rather than back women off, I explicitly ask men to stand up and meet these new demands for increased intimacy.

The problem is that for a man to move into increased intimacy, he must deconstruct masculinity itself. The essence of traditional masculinity is invulnerability. And yet, women across the board are asking men to be in touch with their feelings, to be compassionate to the woman’s feelings, to listen non-defensively, and open their hearts. These are good things for men to do.

Much of the book addresses grandiose thinking. Society has come so far in addressing people’s negative self-talk and low sense of self worth, but I’m curious what we’ve done — or haven’t done — to address thoughts of grandiosity, especially in men?

For well over 50 years, psychology and the self-help movement have been focused on helping people come up from the one-down of shame, of low self-esteem. And that is blessed work. But as a field, we’ve completely ignored helping people come down from the one-up of superiority, entitlement, being above the rules, contempt. In other words: grandiosity.

Grandiosity is what I call “the other self-esteem disorder.” Being inferior and being superior are flipsides of the same coin. Neither is healthy self-esteem. And neither leads to intimacy. We must be “same as,” neither above nor below, superior nor inferior. But we don’t live like that in our day-to-day lives.

In order to lead men, women, and non-binary people into intimacy, we must move them into true self-esteem, being neither better nor worse than the person in front of them. This is especially true for men, and I understand this is a broad generalization, but men in our culture tend to lead from the one-up grandiose position and have covert issues of shame. In contrast, women tend to lead from the one-down shame position and have covert issues of grandiosity. Meanwhile, if you don’t know how to help men come down from the one-up position, you’re not going to help them have a good relationship with themselves and a good relationship with their partners and families. It’s critical work.

I’m fascinated by the concept of generational trauma: how trauma is passed from one generation to the next. How can someone identify trauma patterns in their partner or loved one?

We all marry our unfinished business. We all marry our mothers and fathers, and we all become our mothers and fathers in our marriages. We bring the Adaptive Child parts of us into our relationships, repeating what we learned in our childhoods, often with disastrous consequences.

Our Adaptive Child is forged by two forces. In childhood, I can either react to what is coming at me or I can take it in, internalize it, and use it as a model. For example, if my mother is intrusive, I will react to that by going behind strong walls. Then as an adult male, when my wife asks me a simple question, I may experience her as intrusive like my mother and go behind strong walls once again. This is how childhood adaptations become maladaptive in our adult relationships. So, one way of adapting is through reaction. I have a saying: “Show me the thumbprint, and I’ll tell you about the thumb.” The bigger the intrusion as a child, the bigger the wall as an adult.

Another way adaptation is created is through modeling: you do what you saw everybody else do. When my father — who was loving and violent — was beating me in reaction to his violence, I erected strong walls. No one was going to get through to me. And I took those walls into my marriage. I was a distancer. But at another level, as my father was beating me — particularly as a same-sex parent — he was also teaching me that when a grown man gets angry, this is what he looks like. And as a young man, I struggled with rage issues for many years until I healed in therapy.

Children learn what they live. We bring into our adult relationships the models that we internalized by reacting against them, taking them in and modeling them, or both. These automatic reactions are a direct inheritance of our childhood and usually represent the latest link in a chain that goes back generations. I’m the son of a depressed, violent man. My father was the son of a depressed, violent man. I have two grown boys, and neither of them says that. That is breaking the chain of the legacy, and that is the greatest work of my life.

Some might say your ideology excuses bad behavior — using events that occurred decades prior as scapegoats for abuse. What would be your response to that criticism?

You are not responsible for the way your caregivers treated you. What happened to you is not your responsibility.

But once you hit adulthood, let’s say 18, you are 100 percent responsible for how you handle the damage that occurred to you in childhood. Are you going to heal? Are you going to seek to learn to make better choices? Or are you simply going to repeat the legacy and inflict it on the next generation?

In my first book, I Don’t Want To Talk About It, I wrote: “Family pathology rolls from generation to generation like a fire in the woods, taking down everything in its path, until one person in one generation has the courage to turn and face the flames. That person brings peace to his ancestors and spares the children that follow.” We have all been damaged, we have all been raised by imperfect parents. The question is not, “Were you hurt?” it’s “What are you going to do with that hurt?” Transform it in your own life, or inflict it on the generation that follows?

My wife, the great family therapist Belinda Berman-Real, has a name for those moments of transformation: relational heroism. When every muscle and nerve in your body is screaming to do the same-old, same-old, and you take a breath, find the courage, and reach for something new, that breaks the legacy for you, your family, and the generations that follow.

You pride yourself on breaking your family’s trauma cycle. Tell us a little bit about your upbringing, and how you changed your life trajectory.

Both my wife Belinda and I come from violent backgrounds. My father was warm, loving, overwhelmed, grandiose, and abusive. On the receiving end of his abuse, I felt shame, depressed, unlovable, unworthy. And yet, as I explained earlier, at another level, I also took in those very male abusive behaviors and repeated them in the early years of my life.

When we had kids, Belinda and I were determined not to inflict on our children the kind of violence we had to live through, and we did not. But we could be emotionally violent toward one another in our early years. We’re no longer like that, thankfully; we’ve learned the same skills and used the same skills that we teach others. Our two boys, both now in their thirties, are robustly healthy young men. If you saw our boys, you would say, “Those are well-loved boys.” Between the two of us, my wife and I have broken the chain, transformed the legacy, and that has been the crowning achievement of our life’s work.

Learning to accept love isn’t an easily acquired skill. I’d love for you to talk about Dante’s Inferno and how it relates to the thesis of your work.

Well, it’s hard to say, but the truth is, I never felt loved by my parents growing up. I know they loved me as best they could, but they were very damaged, limited people.

The first person in my life who I felt loved by was a psychotherapist that I saw in my late twenties, three times a week for five years. This son of a gun just loved me. I remember I would come to him with all sorts of complicated, convoluted, self-defeating, not particularly appealing behaviors, and he would never judge me, rarely advise me, and simply be compassionate and loving to me. “What do you think of this?” I would say about some horrible thing I had done. And he would look at me ruefully, smile, and say, “I’m sorry you put yourself through that.”

His love was hard for me to take. I told him that accepting his love was like holding my hand in fire. I would will myself to stay open to it for a few more seconds: 60 seconds today, 90 seconds tomorrow, and 120 seconds the next day. It was hard for me to tolerate the vulnerability of being loved so many years beyond my childhood when I should have felt it.

I once told him the story of Dante’s Inferno, one of my favorite poems. The great philosophers Virgil, Socrates, and so forth don’t exist in the inner circles of hell. They’re in the outer planes before you descend. Dante and Virgil are talking peacefully with these fabulous ancient philosophers, and it begins to rain. And all of these men shriek and run for cover because the rain burns their skin. Dante asks Virgil, “What’s going on?” and Virgil says, “The rain from heaven burns the skin of those down here in hell,” Dante says, “Why?” and Virgil says, “Because it’s from heaven, and we’re not.”

My therapist’s love burned me like rain from heaven, and it was an act of courage to allow myself to move through the pain and into acceptance and receptivity of first his love and, later in my life, those who cared for me—and even my own.