Two weeks ago, thousands gathered on the national mall in Washington, D.C., to read, buy and discuss new literary works at The National Book Festival. But many of the newly published books may not make their way to the shelves of school or public libraries thanks to state legislation that prohibits certain subjects from being taught in classrooms or read about in public libraries.

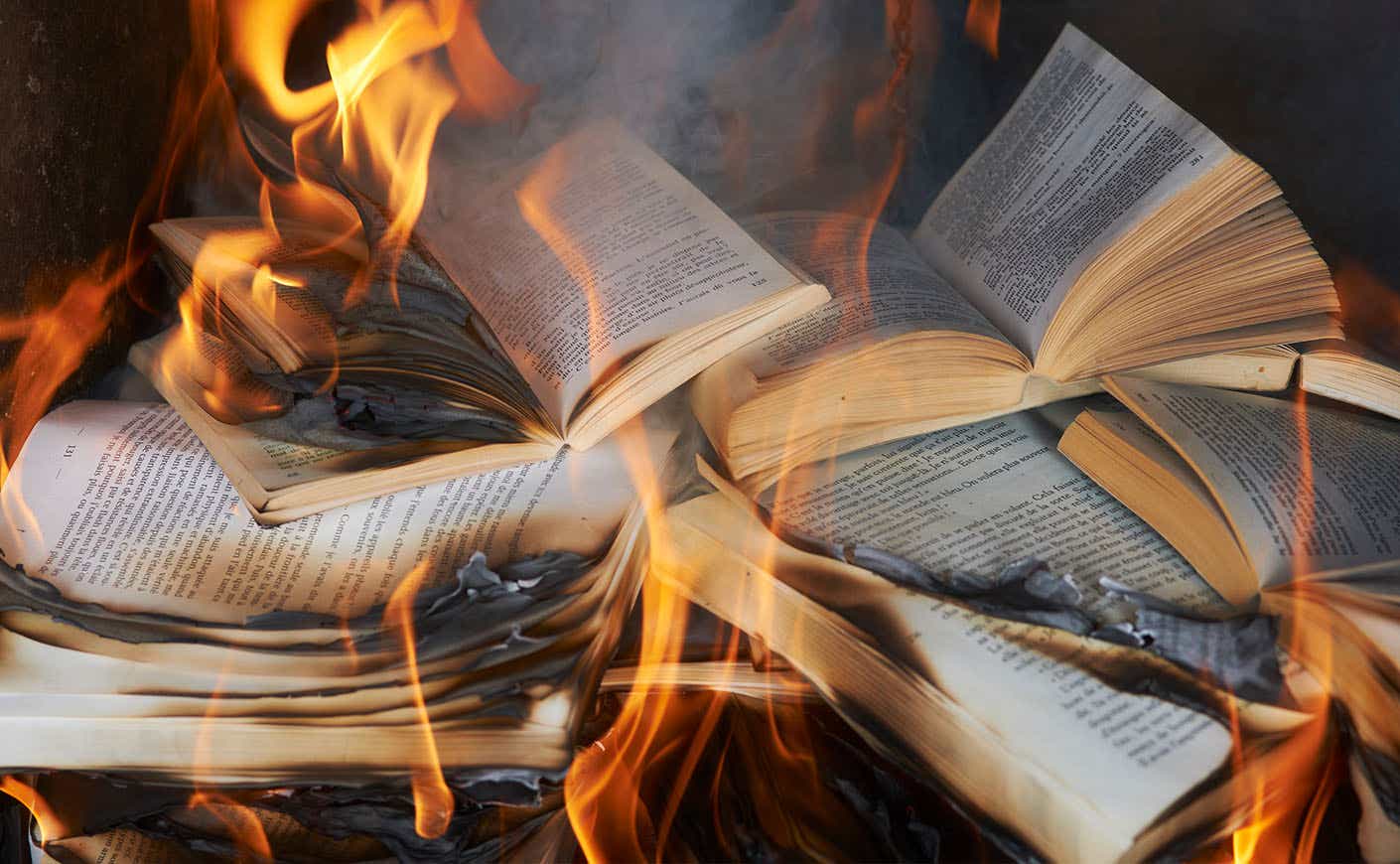

Banned Books Week (September 18th - 22nd) is marking its 40th anniversary. It was first launched in 1982 in response to an upswing in bans on classics like John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath for its reference to sex workers or J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye because of unsavory language. This year the annual commemoration takes on new urgency, as book bans surge across the country. As the chief executives of Brooklyn Public Library (BPL) and free expression organization PEN America, we find ourselves playing defense when it comes to the rights of readers and authors. The freedom to read, a core element of our right to free expression, has come under fire, succumbing to a political movement that has settled on censorship as a favored tactic.

As PEN America’s research has documented, to date in 2022, 137 bills have been introduced in 37 states to limit what books and curriculum can be taught in schools and higher education. Seven such measures have been passed into law, adding to a dozen passed in 2021. They include Florida’s law strictly limiting materials dealing with LGBTQ identities in the classroom, an Oklahoma law banning books deemed to address “critical race theory,” and a Missouri law banning “sexually explicit” books. On top of this, for the nine-month period from July 1, 2021 to March 30, 2022 PEN America has inventoried 1,586 instances of individual books being banned. The broad sweep and loose definitions in these laws have put librarians, school administrators and teachers on the defensive, understandably fearful of how politicians will police these newly drawn lines governing what volumes may rest on a library or classroom shelf.

Just last month, Summer Boismier, a teacher in Norman, Okla., was suspended for shrouding excluded books in a sheet emblazoned with a Books Unbanned QR code allowing students to download off-limits books from the Brooklyn Public Library as part of a national initiative aimed to guarantee access to literature. Administrators accused Boismier of violating legislation prohibiting educators from teaching certain topics related to race and gender. Oklahoma Secretary of Public Education Ryan Walters has taken steps to revoke Boismier’s license. But not everyone agrees. Even as Walters runs for State Superintendent of Schools, placing censorship on the ballot this fall, Oklahomans printed out the Books Unbanned QR code, placed it on posters and stuck it in lawns across Norman.

Americans don’t want their politicians telling them what they can and cannot read. While local legislatures claim to be acting on behalf of their constituents as they impose censorship, book banning is overwhelmingly unpopular among voters. According to data from the American Library Association, seven in 10 voters oppose efforts to remove books from public libraries, with the numbers consistent regardless of party affiliation. Similarly, the large majority of both voters and parents trust public librarians and public school librarians to make decisions about their collections.

Today’s censorious trends threaten all Americans’ First Amendment rights. Legislators are tampering with freedom of speech, turning schools and libraries into battlegrounds in an increasingly polarized America. Titles, including many older classics, are being pulled from bookshelves out of fear that libraries will be defunded and school accreditation will be withdrawn if legislation is enforced. Some librarians have been driven to quit their jobs to avoid being on the frontlines of a culture war they did not sign up to fight.

Elected officials should not dictate what we read; instead, they should allow libraries to do their jobs, and reflect the communities they serve. Material on the shelves in a branch in Brownsville, Texas may be different than what is available at a library in Brownsville, Brooklyn. And while parents have the right and should be monitoring their own children’s reading lists, they should not have the power to edit the lists of their neighbors.

At PEN America and BPL, we strive to protect the authors and books we may personally disagree with, as fervently as those we embrace. BPL’s collection holds more than 2.86 million physical items and 250,000 digital materials. But no library can acquire every book that is published. Our diverse staff contributes to curation, and they listen to our readers. BPL’s Books Unbanned, the program that Summer Boismier tapped into in Oklahoma, allows young Americans from ages 13-21 to obtain a free eCard, providing access to BPL’s full digital collection and learning databases. Since April, nearly 5,000 young people have signed up for the program and they have borrowed nearly 20,000 items from our collection — books they might otherwise have been unable to read.

To build and sustain a healthy democracy, youth must be exposed to a wide breadth of stories and ideas. Children develop a love of reading because they are able to follow their passions and chase their curiosities. Our schools teach critical thinking skills that help ensure that reading and teaching are acts of exposure and exploration rather than indoctrination. Great books help us discover new voices within our communities and discern new strains that emerge within ourselves. By restricting access to books, legislators are shrinking our worlds — and limiting our ability to prepare our children for the duties of citizenship.

As a modern town square, libraries provide a platform for all to debate and discuss the critical questions and dilemmas of our time. This democratic engagement combats the silencing of marginalized voices — from the Left and the Right — in classrooms, in media, in our democracy writ large.

The most potent voices in opposition to censorship are local. Democrats, Republicans and political independents who share faith in free speech and reject censorship must join forces to reclaim the sacred spaces in their communities where citizens can explore books freely without having to worry about politicians looking over their shoulders. If you care about libraries, books and the free flow of ideas, it is time to speak up. Attend a school board meeting, join the library council and let your legislators know that banning books and ideas is not the American way. In recent decades, it could seem as if Banned Books Week harkened back to an earlier era. We would reflect on banned books annually as a reminder that, despite our constitutional safeguards, there remained a risk that the government could suppress ideas. Unfortunately, this tired and discredited tactic has now come back with a vengeance. This year’s Banned Books Week must be a call to action in defense of freedom.

Linda Johnson is the President and CEO of Brooklyn Public Library.

Suzanne Nossel is the CEO of PEN America, a nonprofit dedicated to defending writers and journalists and protecting free speech.