Over the coming weeks and months, first-wavers around the world will observe five years with Long Covid. Many already have. Others with related diseases like myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) — who warned us about the long-term effects of pathogens early in the pandemic — have been sick for decades.

When I was infected in early February 2020, I was 27 and “healthy.” I didn’t have any respiratory symptoms and had no idea my loss of taste and smell or the pain of a suspected blood clot in my calf were results of SARS-CoV-2. Over the coming weeks and months, new symptoms came and went until they set in for good — and divided my life in a fault line between able-bodied and disabled. My two reinfections have worsened my health.

The beginning of the pandemic was a scary and confusing time to develop Long Covid. Few providers could see me, and the ones that did thought I was depressed or anxious since my tests “came back normal.” I began to find other people experiencing the same thing, on social media and in early op-eds, rewriting the narrative that most recover in “two weeks.” Here we are five years later, still sick.

Looking back on half a decade, there have been numerous milestones in Long Covid research, advocacy, and greater societal awareness, many led by people with the disease. There has also been, and continues to be, a lot of loss: There have been more than 25 million global excess deaths from Covid-19, and more than 400 million people are affected by Long Covid, which can be fatal.

The pandemic — and the world’s failure to respond to it adequately — has led to an unsafe society for disabled and immunocompromised people. Many experience deep grief: the loss of friendships, family relationships, marriages, and bodily safety in a hostile society that ignores the ongoing pandemic.

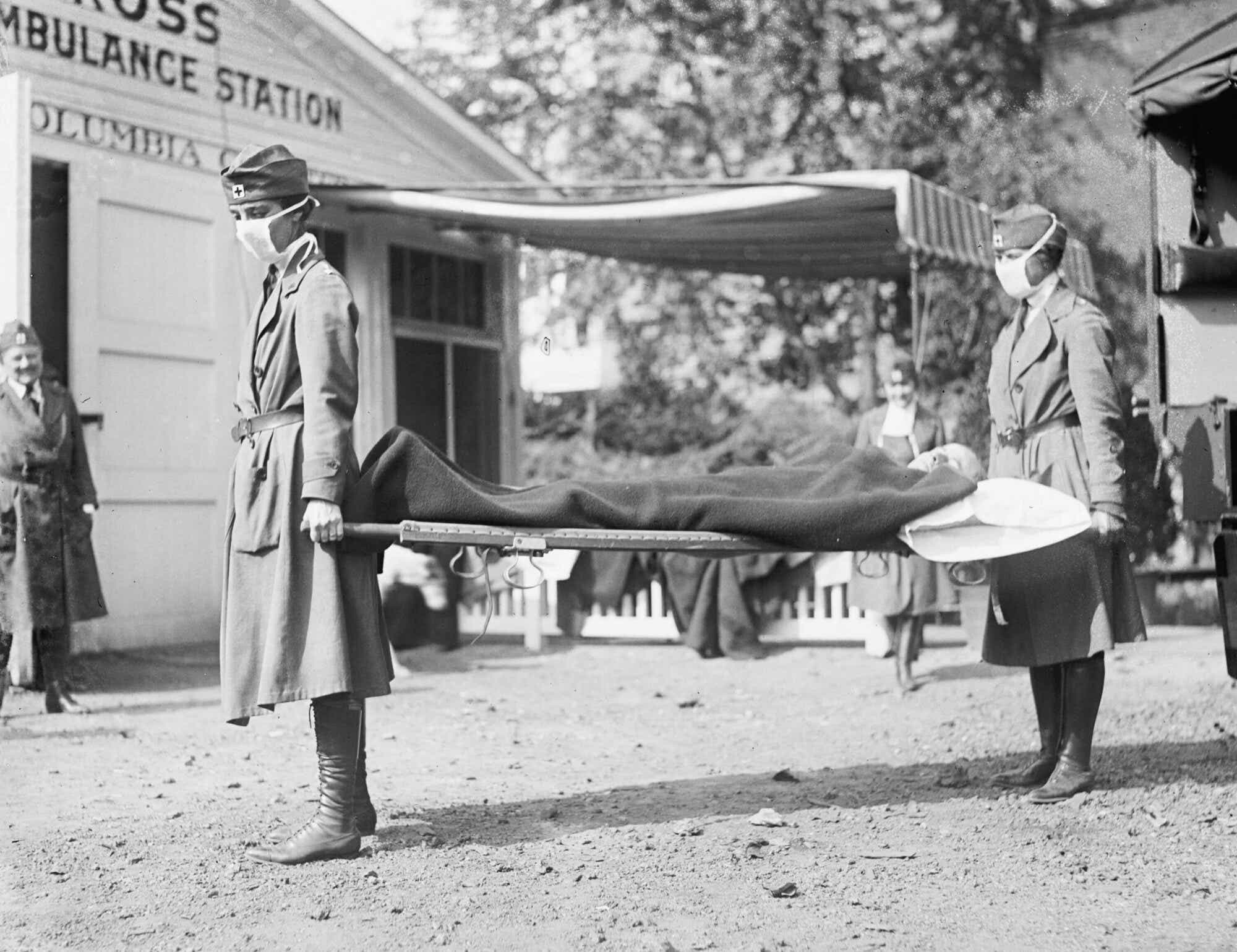

Despite the overwhelming science finding that Covid-19 impacts nearly every organ system and documenting the risk of reinfection, our federal government and health agency leaders deny and minimize the disease. Ableism and late-stage capitalism propel them as the Trump administration rolls back potential progress and disability protections in what one federal worker recently called “fascist and Orwellian” policies. This moment rings with the chilling reminder of the rise of fascism following the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic.

Because of all of this, I am inspired by the bravery of people with Long Covid who have shared their stories and led the way in the face of so much willful indifference and cruelty. We will face these new challenges fueled by the courage and knowledge we have gained over the past five years.

None of our understanding about Long Covid today could exist without people with the disease. We filled out thousands of surveys, showing the disease has more than 200 different symptoms. We gave blood and organ samples to researchers. We informed clinicians on what interventions have moved the needle, leading to important clinical trials. We made life-saving support groups and groundbreaking advocacy organizations. We even set up our own research collaborations that have led to scientific breakthroughs.

Long Covid was also named by a person with the disease. On May 20, 2020, Italian researcher Elisa Perego first tweeted “#LongCovid.” The name quickly gained recognition, as well as the term “Long hauler” from Oregon-based educator Amy Watson’s Long Covid support group, “Long Haul Covid Fighters.”

“Long Covid is short, easy to understand, direct, and works well as a hashtag and a name,” Perego recently told me over email. She explained that it also directly captures the prolonged nature of the disease entity, which was important in early 2020 when health officials said Covid-19 only lasted a couple of weeks.

“Covid survivors found that this was wrong. Covid was long. So, I think the name ‘Long Covid’ greatly helped to convey this message and address early erroneous information,” Perego wrote.

Today, the name continues to address widespread denialism and minimization. Often media outlets state that Long Covid lasts for only “weeks or months,” or that most cases “resolve.” Unfortunately, neither is the case.

Many studies have shown that a large majority of people with Long Covid have not recovered. Millions of us are proof that Long Covid can last half a decade, and that it (and related diseases triggered by Covid-19) are lifelong. This mirrors chronic illness from earlier pathogens: a 2021 study about SARS-CoV-1 found that people infected with this virus were still disabled nearly two decades later.

For Perego, some of the top milestones of Long Covid advocacy include scientific publications adopting the term and advocacy initiatives like internationally-recognized Long Covid Awareness Day on March 15. Others I spoke with cited Ed Yong’s Pulitzer Prize-winning reporting on the disease and ME, the 2024 Senate hearing on Long Covid, and the resulting Long Covid Research Moonshot Act. Others referenced protests and demonstrations around the world calling attention to Long Covid.

“Thanks to the patient community, we saw quick action and acknowledgment of Long Covid early on,” said Gina Assaf, co-founder of the Patient-Led Research Collaborative. “I’m forever in awe of our community and what we did there.”

This, and so many other forms of advocacy, have paved the way for attention on the disease. Contrary to the mainstream media’s framing of Long Covid as “mysterious,” Assaf said that we know a lot about the disease. In fact, on PubMed, there are over 38,000 papers using the term, and researchers are zeroing in on its potential causes, including viral persistence, immune dysregulation, and reactivated viruses.

As we face probable challenges in funding and research in the U.S., Assaf said it will be important for scientists to focus on global collaboration and to consult with patients. PLRC funded vital research last year through their patient-led fund, including a study that found muscle abnormalities in people with Long Covid. They’ve also developed patient-led research scorecards to increase patient insight and hold researchers accountable for pursuing high-reward projects.

While scientists have found promising leads — there are still no approved treatments.

Activists and Long Covid advocacy groups have raised money to help further investigate viral persistence, a theory private researchers like those in Polybio’s international consortium continue to investigate. Other promising private researchers like the Bateman Horne Center and Open Medicine Foundation also collaborate with patients, leading clinical trials on data-backed drugs and studies into potential biomarkers.

“There are important pockets of advancements,” Assaf said. “I’m optimistic and hopeful for us … I hope clinical trials will help us understand what is and isn’t working.”

Assaf’s family has been particularly impacted by Long Covid; on top of Assaf, her sister is severely disabled from Long Covid. “It has been hard on our family, financially and emotionally,” she said.

Over the past five years, we’ve seen Long Covid’s wide reach as multiple family members develop it, couples come down with the illness, and people from all walks of life and every age, including millions of children, develop the disease..

While scientists have found promising leads — there are still no approved treatments for Long Covid. Some of the related diseases people with Long Covid develop, like dysautonomia and mast cell activation syndrome, have treatments that may offer some relief, but finding providers knowledgeable on them can be difficult.

Many people with Long Covid are also unable to access these treatments for co-diagnoses, said Tracey Thompson, the founder of the Black Indigenous Racialized Covid Health project. In the first years of the pandemic, Thompson said she followed every study for a glimmer of hope.

“I’ve stopped reading papers,” she said. “It’s not like I’ve stopped looking … but I just had to do it for my own well being.”

While scientists look for treatments, Thompson stressed the importance of preventing Covid-19. The disease continues to spread, kill, and disable, particularly in marginalized communities, which often have higher Covid-19 rates and less access to care.

“The message hasn’t changed,” Thompson said: wear a mask to prevent infection, and if you do get infected, rest up. “I want less people hurt. I want less people damaged. I want less people infected … Anything you can do to mitigate harm is a good idea.”

Over the years, we’ve seen mask blocs, clean air groups, and other mutual aid efforts step in to help mitigate the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in their communities as our government failed us. People with Long Covid and other disabilities lead many of these groups. These stop-gap measures have proven life-saving in a society hell bent on mass infection.

People who reach out to Thompson about Long Covid often assume there are clinics where one can go “get all patched up.” But if there were, “we wouldn’t be going on about it for five years,” she said. “We wouldn’t be out there beating these drums that no one wants to listen to.”

We keep beating these drums because we care about our loved ones and community members. While much of society does not consider or advocate for us, we continue to deliver the news and share our stories, study after study, life-changing case after life-changing case, to warn them about the lack of safety nets and cures once you develop Long Covid.

We do it as mutual aid organizers delivering masks and tests and homemade meals. We do it as researchers studying mitochondrial dysfunction and viral persistence. We do it as activists dropping banners and hurling public health messages on billboards. We do much of it from bed as we rest and pace.

Over the years, covering Long Covid has reshaped my understanding of journalism. I once dreamed of writing gorgeous long-form features — now I value the importance of service journalism more than any form of writing. I want to continue to inform our community as we fight ableism and navigate the next half-decade of Long Covid. As we navigate new treatments, biomarkers, and, of course, more denialism.

People with Long Covid are courageous. We will continue to share our stories and do the work the world is too scared to take on.

This essay was republished with permission from The Sick Times, a journalist-founded website chronicling the Long Covid crisis.