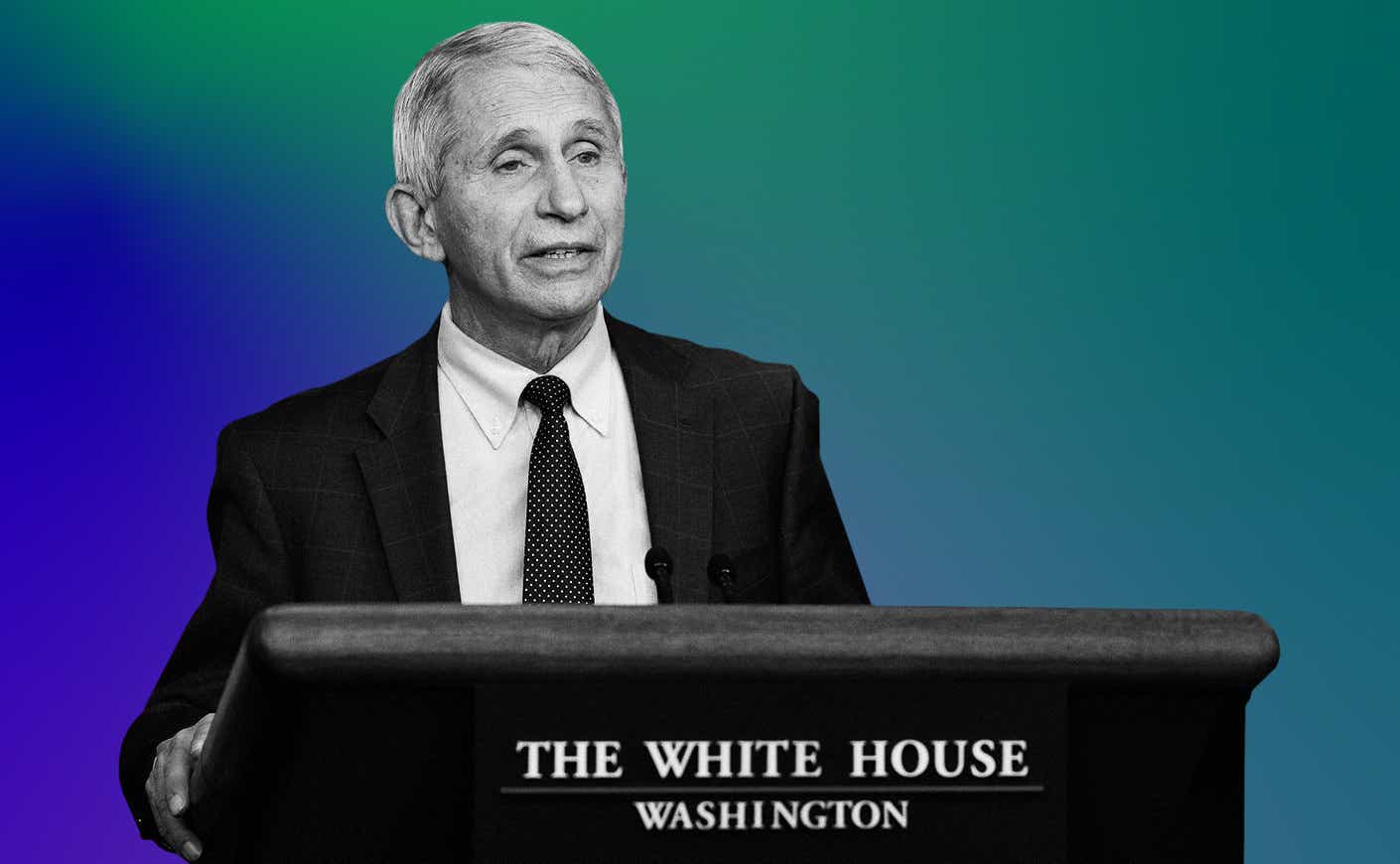

As BA.5 infections continue to rise and the country races to contain monkeypox, Dr. Anthony Fauci remains one of the busiest men in America. But the nation’s top infectious disease expert still managed to squeeze us into his schedule, chatting with Katie about everything from his recent bout with Covid-19 to what we can expect from the next generation of vaccines, and why he may soon be leaving the NIH but won't be retiring just yet.

Watch the full interview or read edited excerpts below.

Katie Couric: You recently tested positive for Covid-19. What were your symptoms?

Dr. Fauci: I think it was on a Wednesday evening, as I was getting ready to go to bed. I felt a little scratchiness in my throat, and I thought it wasn't a sore throat. But when I woke up in the morning, it was a little bit more severe. I didn't feel sick at all. I just thought, Let me take a test, and it came out strongly positive. So I went on Paxlovid immediately, and over the next 18 hours, I developed a little bit of a sniffle. I didn't feel great, but it was mostly fatigue. I went on Paxlovid and the symptoms disappeared within 18 hours. But then I was one of the ones that had a bit of a rebound.

So many people are having this rebound where the symptoms fade and then return, and you test positive again after testing negative. Why is that happening so often?

We don't know exactly why. But it may be that when you take Paxlovid early on, like you’re supposed to, that you don't give the body enough of a chance to respond to the virus immunologically. So when you withdraw the drug, the virus comes back. I'm glad I'm talking to you about it to really dissolve confusion: Paxlovid is doing exactly what you're asking it to do. You're asking it to prevent you progressing to severe disease leading to hospitalization. If you get a rebound for a day or two and the symptoms return, almost invariably they're very, very mild.

We still don't know how common this rebound is: Some general studies show 2 percent, and others show maybe 8 percent. Regardless, many people seem to be getting this rebound. But we shouldn't let that be a reason not to take Paxlovid, because it will keep you out of the hospital.

BA.5 has proven to be not only more contagious, but hospitalizations are on the rise. How concerned are you about this latest strain?

The thing that's concerning to me is that the deaths are still hanging around 300 to 400 a day. And if you do the math on that, you're talking over 100,000 deaths per year, which is unacceptable. So we've gotta get that number much lower, and you do that through common sense public health measures. If you're not vaccinated, get vaccinated. If you're not up to date on your boosters, get boosted. If you're concerned about whether or not you're infected, tests are widely available and free. If a test is positive and you're in a risk category, go on Paxlovid. If you go to the computer and click on the CDC map and you see that the county that you're in is an orange or a red zone, then when you're in a large, congregate indoor setting, wear a mask.

A lot of my followers are concerned because the boosters don't seem to be efficacious against some of these new strains. So what's the point of getting them?

Well, that's a great question, and it's an understandable source of confusion. But look at the data. We're asking predominantly that vaccines prevent us from getting so ill that we’d have to go to the hospital. Now, we're getting people who are vaccinated and boosted who are getting infected — like me or the President of the United States. But the vaccine does prevent you from progressing to severe disease. What we do need for the future are vaccines that'll give you a greater breadth and durability of protection, as well as a new form of vaccine that you could administer intranasally.

I know you've talked about a pan-coronavirus vaccine, but it sounds complicated and potentially very difficult to achieve. How realistic is that? And when do you think something like that might be available?

You want to take incremental steps and start off with a pan-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine that gets all of the different variants that we've already experienced, as well as any variant of that particular virus that we might experience in the future, like this fall or this winter. The next step is to develop a vaccine that protects against the group of coronaviruses that are clustered around the bat-human interface, so that if we get another jumping of the species from an animal to a human, we'll be prepared. And then the ultimate holy grail is to get one that includes all coronaviruses, including the common cold coronavirus. Now that's aspirational. The first step that I mentioned, I think realistically, it's gonna take a couple of years. To make sure it's proven to be safe and effective in a big study, that's not gonna happen in a few months.

Let's move on to monkeypox: As of right now, at the end of July, there are 4,000 cases documented here in the U.S. — 99 percent affect men who have sex with other men. But the virus was first discovered in 1958. So why are we seeing this outbreak now?

Monkeypox is a virus that's endemic in certain central African and west African countries. It almost invariably goes from an animal and jumps to a human, with some exceptions — at least up until now. We're investigating if anything has changed recently, but in sub-Saharan Africa, in central Africa, usually when it gets into the human host, that's a dead end. What apparently happened, and we have to make sure we nail this down epidemiologically, is that associated with gay pride galas and get-togethers, the virus got inserted into this population. The modality of spread is close skin-to-skin contact, as you would have in a sexual encounter — though not exclusively in a sexual encounter. Now, when you have multiple sexual partners where you don't know the status of that person, that is a very easy way for a virus to spread within a demographic group.

It’s likely someone was infected in Africa and then entered this community. Then you wind up now, where monkeypox is predominantly in men who have sex with men. In the early years of HIV, we didn't know what the agent was, we didn't have a diagnostic, we didn't have a therapy, and we didn't — and still don't — have a vaccine. We were swimming in the dark. But right now in this situation, we have a vaccine, we have testing, and we have therapeutics. And we've gotta reach out into the community to alert both the community and the physicians and healthcare providers that take care of them, that we have a problem that's spreading.

The real challenge is to get those interventions to the people that need them in an expeditious manner. We started off with very few tests: 6,000 a week. We now have 80,000 a week. And we know we have a vaccine that works, but we've gotta get it from where it was stockpiled and get it distributed. Right now, things are looking much, much better. You know, we have about 300,000 doses already distributed and we're gonna have another 400,000 distributed very soon. Then we have another additional 800,000 that we're gonna be able to get out, we hope. We've also gotta cut down the paperwork and the logistics to get the right treatments to people who need them.

A lot of people wanted me to ask you if monkeypox can be transmitted via airborne exposure. And while we're on the subject, if I'm in the company of someone who was diagnosed with monkeypox, what are my next steps?

Right now we — the CDC together with the NIH — are studying the natural history of this virus. We generally know how it acts and acted in Southern Africa, but we wanna make sure we understand that there's nothing different about this variation. And thus far, it looks like it spreads through close skin-to-skin contact with someone who has monkeypox lesions. There's no data to indicate that it spreads any other way. We do know from experience with smallpox and monkeypox that it can be spread through contaminated clothing or other objects.

You wanna isolate a person while they're shedding virus — if you have a very painful lesion that's spread all over you, it's very clear that you have monkeypox. But in some cases, it may not be so clear. So you want to educate the community about what they need to look out for. But I would not wanna say that people need to worry about being near somebody, because then you get stigma, and stigma is the enemy of public health. So we shouldn't be saying, "Well, now the entire population is at high risk." It's not. We're gonna keep an eye on what we call the natural history and the evolution of this. And the more we track it, the more knowledge we'll have, and the more knowledge we have, the more concrete recommendations can be made.

You've announced that you're stepping down at the end of President Biden's first term. When you think about all the challenges you've faced and everything that you've accomplished, what are you proudest of?

Well, first of all, it's a misperception and I'll clarify it for you. Someone asked me if Donald Trump became president in January 2025, would I serve under him. And I said, very honestly, whether Donald Trump or another Republican becomes president or Joe Biden gets a second term, I do not plan to be in this job by January, 20, 2025. The headline was I'm staying at the job until January 20, 2025. That's not the case. I will retire from federal service anywhere between now and then, and I haven't made up my mind when that's gonna be. One little footnote: What I jokingly-but-seriously object to is the word "retire." Because even when I step down from federal service, I will continue to do the things that you're asking me about in my career, in a different venue.

What do I feel the proudest of? Well, naturally I feel proud of my 54 years at the NIH. Curing certain inflammatory diseases — earlier, before AIDS — that were rare but quite deadly, establishing the AIDS program at the NIH, being an important part of the development of therapies that have saved millions of lives. Also, being the principal architect with George W. Bush, our then-president, of the PEPFAR program, which has saved about 20 million lives. And having the honor and the privilege of serving seven presidents. So those are the things that I've done, and some version of that I'll very likely continue in a different venue when I leave the federal service.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity