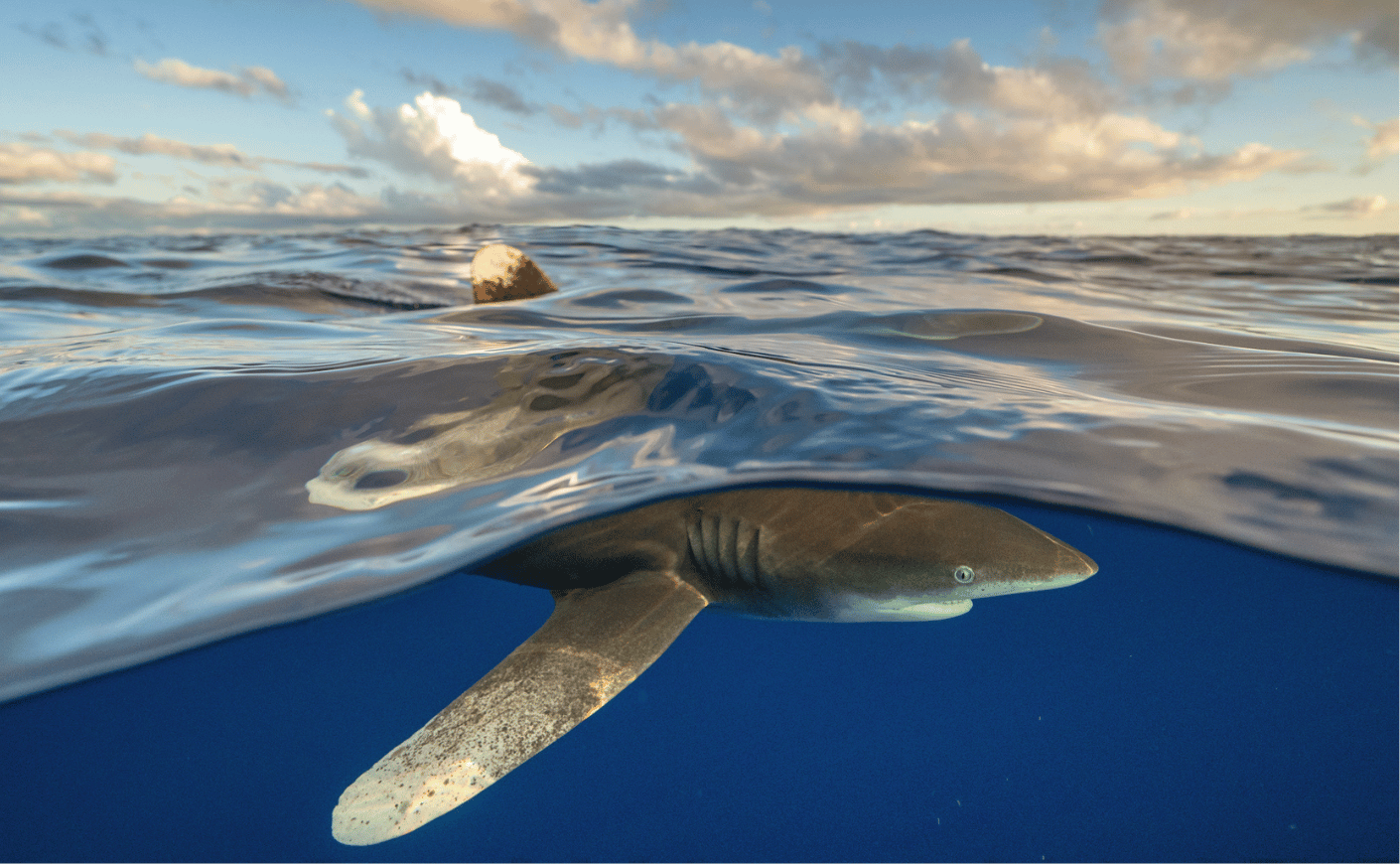

The first oceanic whitetip appeared as a shadow in the deep blue, rising slowly from the depths off the island of Mayaguana in the Bahamas. As it closed in, its distinct fins caught the light, and I felt that electric thrill every diver knows: when predator and human lock eyes across an ancient divide.

I had come to dispel myths. The oceanic whitetip shark has been demonized for decades, cast as the villain in countless shipwreck stories and feared as an aggressive man-eater. But what I discovered in these crystalline waters was more nuanced, more fascinating, and ultimately more tragic than any Hollywood narrative could capture.

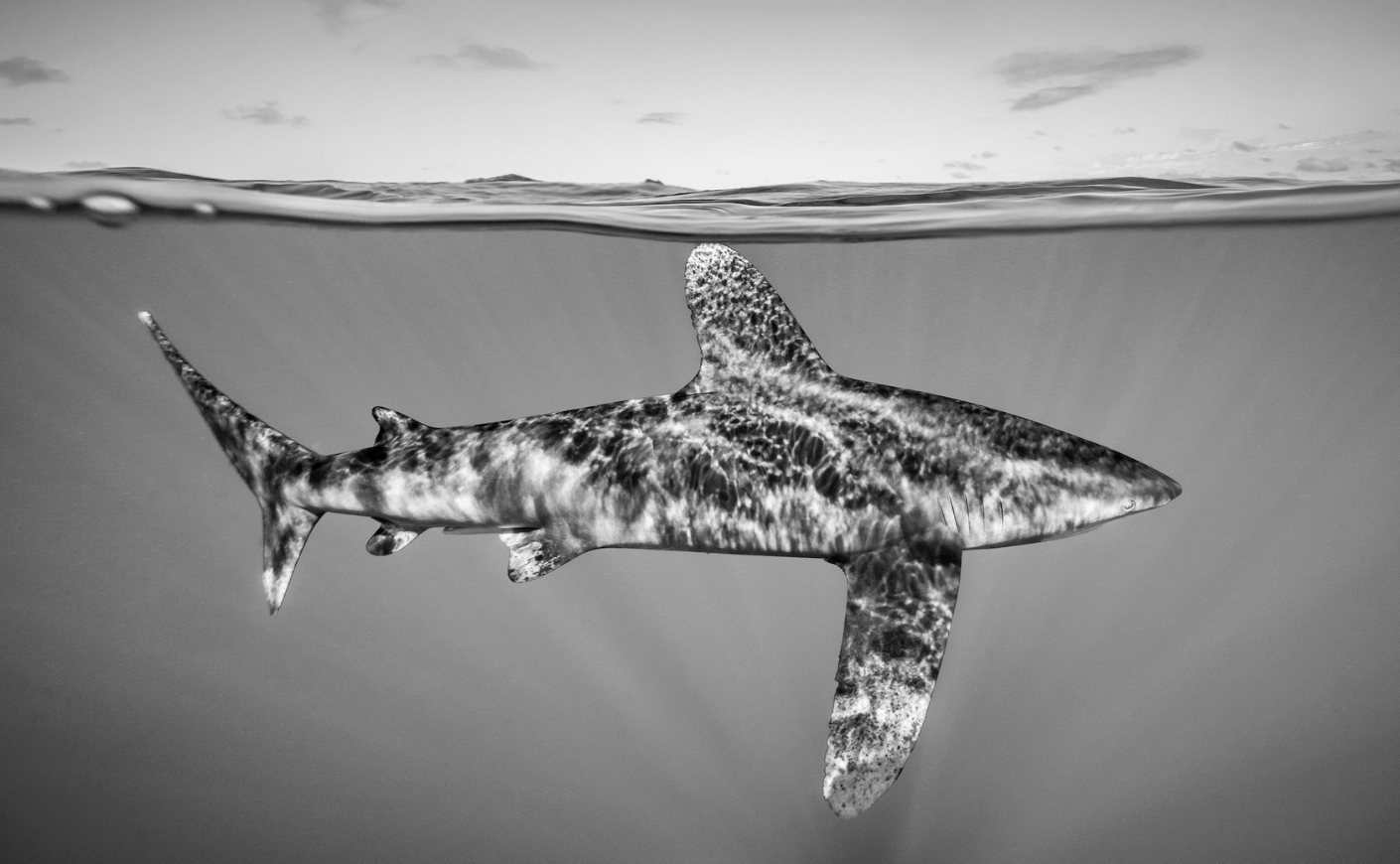

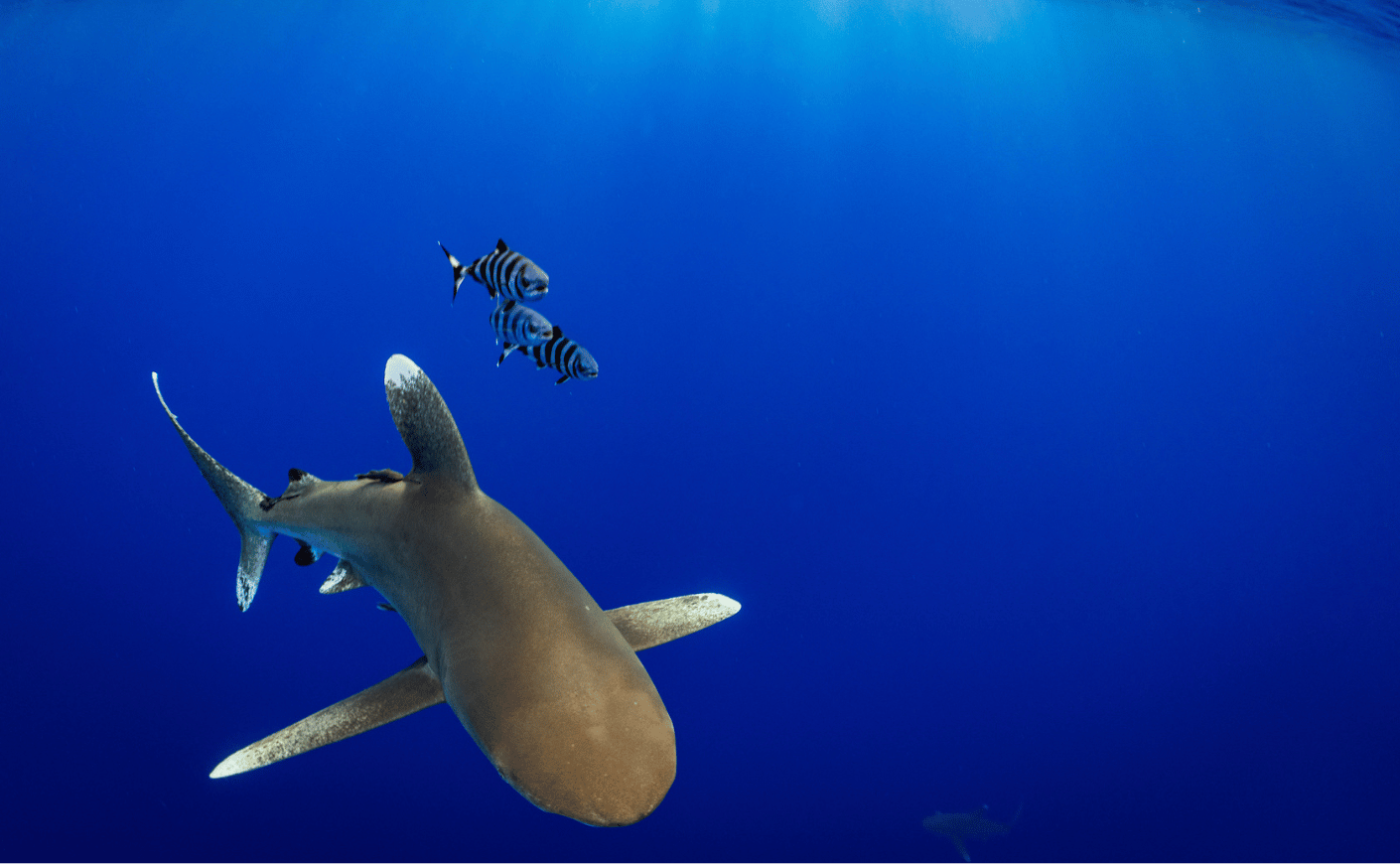

That first shark was breathtaking. The way they move is different from other sharks, more elegant, almost like a jet liner. Scientists believe this species was once the most common large predator on Earth, ruling the open ocean like wolves ruled the American wilderness. I watched it circle, studying my partner Paul Nicklen and I with a bold curiosity that has defined this species for millions of years. This is an animal that investigates first and asks questions later, a necessary trait for an apex predator in the world's largest ecosystem.

Then the second shark arrived. And the third.

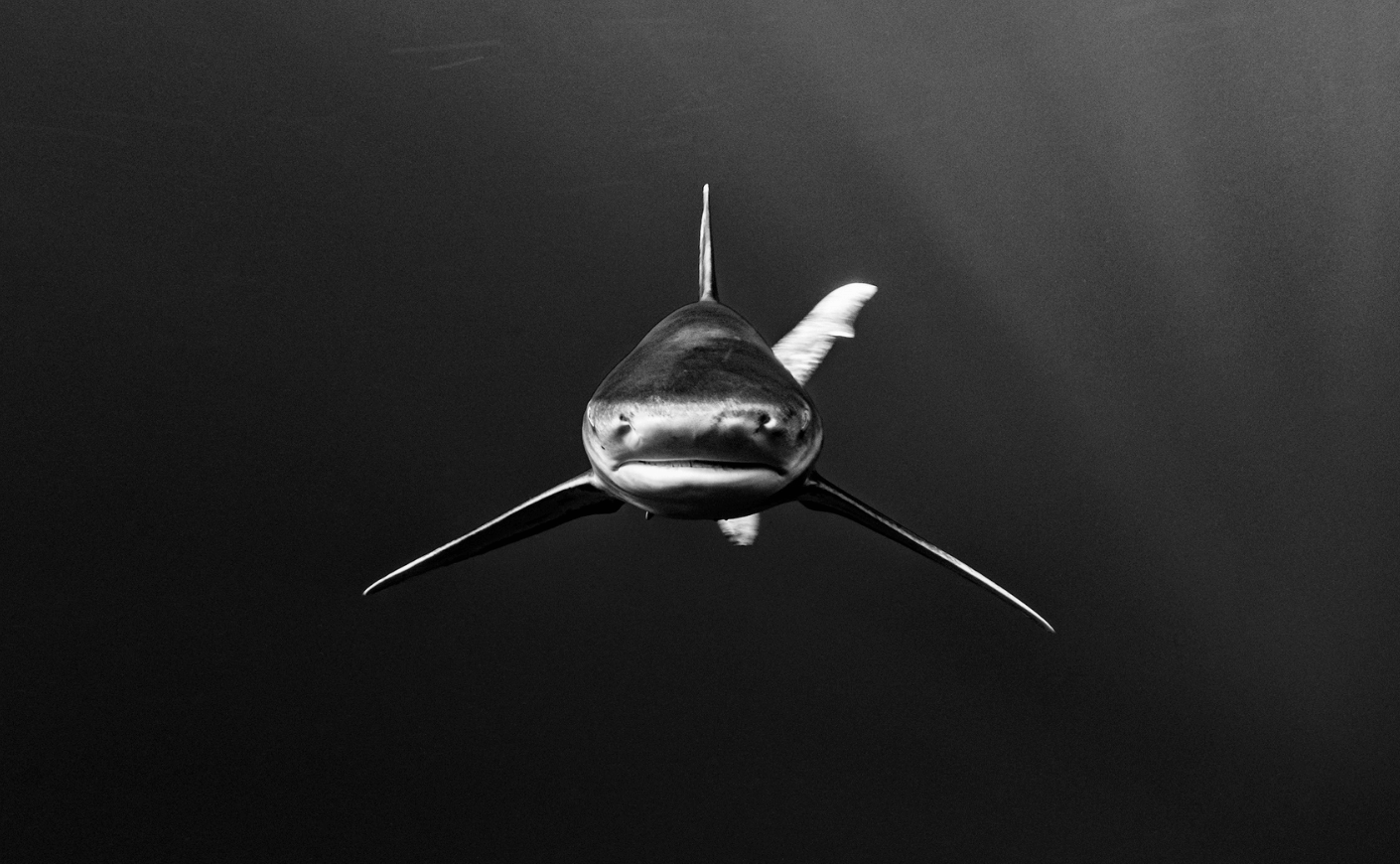

What began as a graceful ballet transformed into something altogether different. These weren't solitary hunters. They were working together with the coordinated intelligence of a wolf pack. Like the velociraptors in Jurassic Park, one would approach from the front, commanding my attention, while others slipped in behind. Paul and I instinctively moved back-to-back, our heads on a swivel tracking the growing number of white-tipped fins cutting through the water around us.

By the time six or seven sharks had joined the party, I understood viscerally why sailors called them “shipwreck sharks.” This wasn't mindless aggression, but something calculated and methodical. These animals were testing boundaries, probing for weakness, and using their numbers to gain advantage.

We exited the water with a newfound respect and understanding of these beautiful animals.

The collapse of a giant

Oceanic whitetips spend their lives far offshore, patrolling the open ocean where food is scarce, unpredictable, and often found only by arriving first. To survive here, you have to be curious and bold. As apex predators, these sharks help maintain balance in food webs that stretch across entire oceans. Remove predators like them, and everything beneath begins to unravel.

The same aggressive curiosity and fearless nature that has kept oceanic whitetips thriving for millennia has ironically become their death sentence in the modern ocean. Once in the millions (perhaps billions), their populations have collapsed by 80 to 90 percent, and some studies estimate 95 to 98 percent in just three generations. Three. The most common large predator on Earth has been driven to the edge of extinction in the time it takes a human to retire.

A landmark protection

Recently, however, something remarkable happened in a conference hall thousands of miles from the nearest ocean. Countries gathered in Uzbekistan for a meeting of CITES, the global treaty that regulates international trade of wildlife, and voted to give oceanic whitetip sharks the highest level of protection it offers. For the first time in CITES’ 50-year history, a shark species received a complete ban on international commercial trade.

The vote came from 83 percent of participating nations, with more than 50 governments co-sponsoring the proposal championed by Panama. It was, by all accounts, a watershed moment.

“Ocean species deserve the same urgency and protection as wildlife on land,” said Luke Warwick, Director of Shark & Ray Conservation at the Wildlife Conservation Society, “and the world will not stand by and watch as iconic sharks slip toward extinction."

But why did it take so long? Why did we let populations crash by 90 percent before taking decisive action?

The answer swims in every bite of tuna we eat.

Fishing, fins, and the price of curiosity

Oceanic whitetips live in the same waters where industrial longline fleets deploy millions of baited hooks. Every tuna fishing operation becomes a potential death trap for these curious predators.

When a tuna fights on a longline, thrashing and bleeding hundreds of feet below the surface, oceanic whitetips investigate. And they get hooked. Over and over and over again.

Switching from wire leaders, which sharks cannot bite through, to monofilament leaders that they can escape from could save an estimated 30,000 whitetips annually. The Hawaii Longline Association made this change in 2020. The Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission followed in 2022, but enforcement remains inconsistent worldwide.

But that’s not the only threat oceanic whitetips face.

Their large, distinctive fins are highly valued in the shark fin trade. A recent investigation revealed that illegal trade in oceanic whitetip fins exceeds official reports by 70 times. That level of laundering is exactly what the new CITES protections aim to address. A complete ban on international trade closes loopholes and removes financial incentives, but treaties are only as strong as their enforcement, and enforcement happens in ports, customs offices, and seafood markets far from conference halls.

What we can do

The real power to save oceanic whitetips rests with us, every time we decide what seafood to buy.

Choosing sustainably caught tuna matters. Tuna caught with what is known as “hook and line” (or one fish at a time) is the safest for sharks. Asking where your seafood comes from matters. Supporting restaurants and suppliers that prioritize ocean health matters. Every purchasing decision either funds unsustainable longline operations that are killing these sharks or supports alternatives that don’t.

When I think back to that moment in the water, surrounded by those intelligent, curious, dangerous animals, the only fear I feel is for how close we are to losing them. Oceanic whitetips are survivors from an ancient lineage now facing something they never evolved to handle: us.

The new protections from CITES offer genuine hope. But hope requires action, enforcement, and awareness. The question isn't whether oceanic whitetips can recover, because they can. The question is whether we’ll give them the chance.

That magnificent creature rising from the deep blue off Mayaguana deserves better than to become a footnote in the extinction ledger. And the choice to give her that chance starts with what’s on our plates.

Paul Nicklen and Cristina Mittermeier co-founded SeaLegacy in 2014. SeaLegacy’s mission is to inspire people to fall in love with the ocean, amplify a network of changemakers around the world, and catalyze hands-on diplomacy through hopeful, world-class visual storytelling. For more updates on their meaningful work, learn more about SeaLegacy, and subscribe to Ripple Effect, Katie Couric Media’s sustainability newsletter.