In 2010, life changed forever for Debra Meyerson and her husband, Steve Zuckerman.

On Labor Day weekend that year, Debra suffered a severe stroke. She spent two months in four different hospitals and emerged with extreme weakness on her right side (a substantial improvement from the initial near-complete paralysis) and virtually no ability to make sound, let alone speak. Needless to say, it was a crushing blow for someone who thought she was about to start teaching the fall semester at Stanford University.

Debra and Steve braced themselves for an arduous rehabilitation effort and a period of disrupted living, believing that life would, after a time, return to normal. Forever the optimist, Steve said frequently that, before long, they would “look back on this as a six-month blip” and get back to life as they knew it. The couple modified that expression to project a 12-month blip, then a two-year blip. Their optimism (some might say denial — but nobody really did know how the recovery would unfold) was certainly valuable to their motivation and mood, but life had other plans for them.

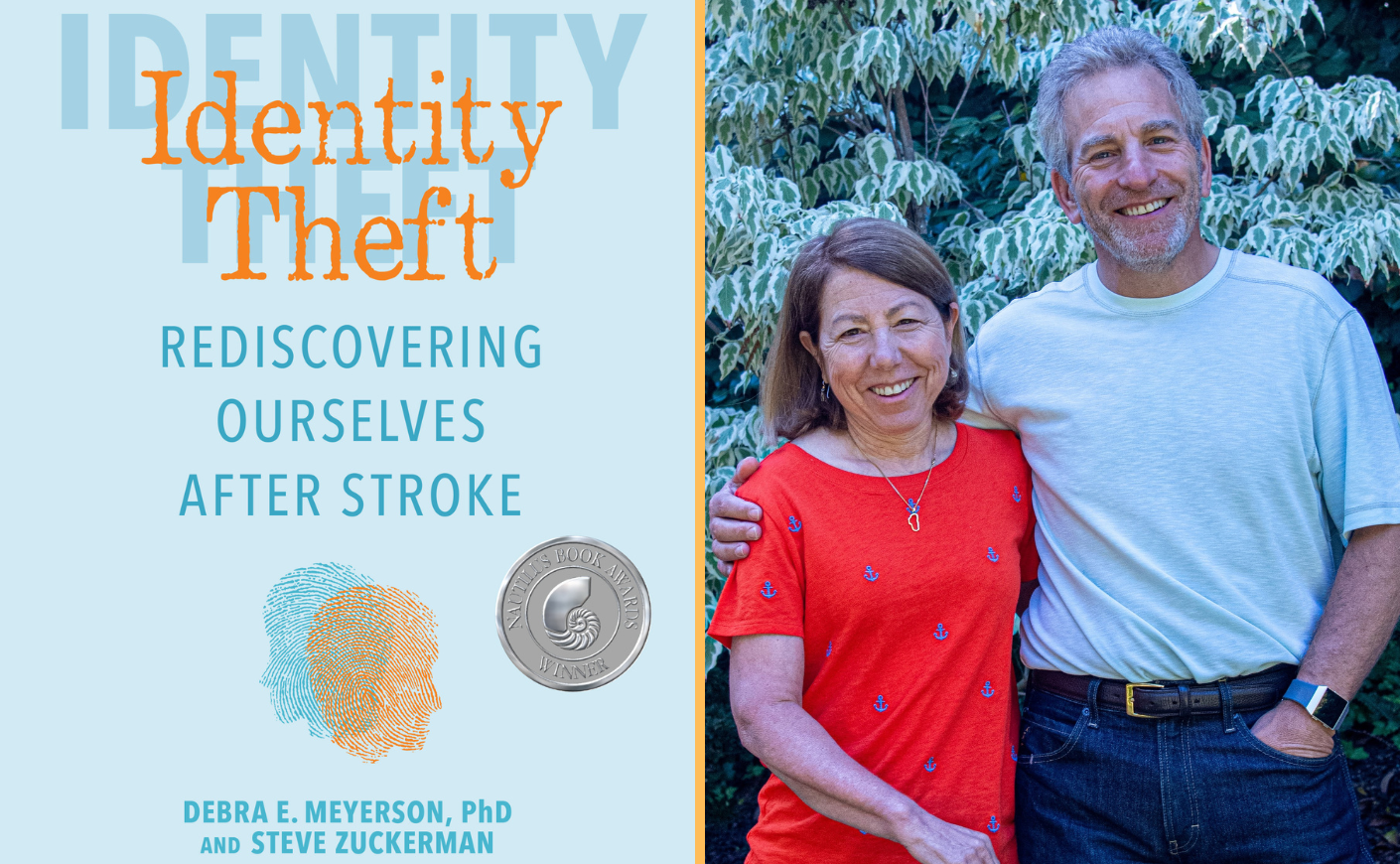

After three years of virtually full-time therapy, ongoing disabilities didn’t allow Debra to fulfill the full scope of her faculty role at Stanford. Most problematic was aphasia, a communication disorder that, in her case, prevented her from putting words to the thoughts in her head. School policy had limits on the length of medical leave, and she had to give up her tenured professorship. That hard reality set off an “identity crisis” that, among other things, led the couple into the five-year journey to write the first edition of their book, Identity Theft: Rediscovering Ourselves After Stroke.

At the outset, Debra decided to write a book to prove that she could. She was holding fast to her identity as an academic and a scholar. But the process of research and writing quickly became her learning journey — their learning journey.

Almost everything Debra and Steve were told during those first three years of recovery — and the support they were offered — had been focused on rehabilitation, and maybe just a bit on how to adapt to life with disabilities. Nobody told them about the equally critical journey to rebuild their identities as a critical step on the path to rebuilding their lives. That is what ultimately drove the content of Identity Theft, which hit shelves in 2019.

When inventory of this book’s first edition began to run low, the authors asked their publisher about a second printing. They suggested a second edition instead. Candidly, Debra and Steve say they were hesitant. Writing the first edition, and several writing projects since, taught them that doing projects this big together — especially writing projects that are so tough with aphasia — creates a lot of stress on a relationship.

Ultimately, their excitement for the opportunity to improve their work and, hopefully, contribute more to the stroke community outweighed their concern. They took the plunge, and the second edition of Identity Theft is available now. Below, in an excerpt from the book that's told from Debra's perspective, the authors unpack what stroke recovery really looks like — and why the patient's attitude makes such a significant difference in their progress.

The Grind of Therapy

Four months after my stroke, my family gathered for the winter holiday. During breakfast at a restaurant one morning, they struggled to remember the name of the popular movie about a pig that was trained to herd sheep. As everyone else fumbled unsuccessfully through their memories, I suddenly blurted out, “Babe!”

All heads whipped around to look at me. I looked astonished. They were beaming. Steve began hooting, and everyone started high-fiving me and each other. “Babe” was the first unprompted word I had spoken since my stroke. I had regained about 20 words through practiced therapy and repetition, but this was the first original thought to pass my lips in months.

Unfortunately, those breakthrough moments are rare. After eight years of daily effort and countless hours of work, I’ve had maybe 10 dramatic breakthroughs, but progress has been steady. I can now generally find the words I need to get across a simple message, but not always. I cannot share the more complex thoughts I still carry in my brain.

My physical recovery has been equally meaningful and excruciatingly slow. Often, I don't even notice my own improvements until somebody I haven't seen in a while points them out. Long term, of course, I can see the tremendous improvement. I now have relatively good mobility, but I walk with a limp and still have no functional use of my right hand. I have days when my leg is a little looser or words come a little easier, and others when my recent gains seem to recede.

The term “recovery” is often used after strokes, and it’s a word that can evoke thoughts of rest — passively letting the body heal. However, real gains come not just from time and rest, but from rigorous work and training. For most stroke survivors, this means hours of physical, speech, and occupational therapy. We fight through the physical and verbal challenges of daily life, including the slow conversations interrupted by “No, say it right” from family members.

Rehab is a full-time commitment after stroke, and even when a full recovery becomes unlikely (if not impossible), therapy continues because incremental improvements are still worth fighting for. It is a grind; it is frustrating; and, at times, the slow rate of improvement does not seem worth the effort. But there are also times of inspiration, markers of progress beyond what you’re told to expect, and milestones that open up new levels of independence and keep us moving.

Often, my morning begins with 30 to 60 minutes of stretching to get my arm and leg loose and primed for the day. For the first few years, I had nearly daily Skype sessions with my mother to check in and work through speech exercises. When I hung up with her, I would often turn to Rosetta Stone and work my way through more exercises to relearn English.

I wanted to do even more and move faster. The standard three hours per day didn’t feel as if it was enough. I wanted to get back to who I was before this nightmare began, so I continued practicing as much as I possibly could. With every new task in therapy, I tried to do even more than the prescribed amount. After my stroke, I wanted nothing more than to power through, work myself nonstop into recovery, and put the experience behind me

Intel executive Sean Maloney called therapy the hardest full-time job he’d ever had, and he’s right in so many ways. For many of us, rehab is still a defining, tireless part of our daily lives for years after our strokes. We must orient our lives around it, making trade-offs between therapy and other parts of life. And recovery is not something we put behind us like a healed injury or mended wound: Our recovery becomes part of us, a part of our identity, the way a job is to most people.

Jim Indelicato spent 40 years in the U.S. Air Force and Air National Guard. In the latter, he was in charge of physical fitness, but he took early retirement when the base moved. As a lifelong fixer, he was planning to start his own home-rehabbing business. A 32-time marathoner, Jim has been married to his wife, Diane, for 47 years, and they have been best friends since he was 15 and she was 12. Together, they have raised a son and two daughters, and they all live in St. Louis.

On Sept. 16, 2010, Jim was driving his big red Silverado pickup truck with “RUN” on the license plate to help rebuild his mother-in-law’s house when he started to lose vision. He pulled the truck over and vomited. His vision briefly recovered, and he drove another mile before he had to pull over and turn the truck off. Five hours later, Jim was in the ICU of St. Anthony’s Hospital. He had forgotten how to swallow and was in danger of drowning in his own saliva.

After much confusion, the doctors determined that Jim had a tiny blood clot in his brain stem, the part of the brain that controls basic functions like swallowing and breathing. Six different times while at St. Anthony’s, Jim went into respiratory distress, each time for longer than the typical one to two days. The doctors tried multiple types of feeding tubes and respirators, but each had problems. Eventually, they installed a feeding tube that bypassed the throat and sent nutrients straight to the stomach, and they performed a tracheotomy to bring air directly into his throat.

Because he couldn’t swallow, saliva had built up in his ears, and he couldn’t hear much. That had thrown his balance off so much that he was too dizzy to read what his family wrote to communicate with him. “I think that was when we were at our lowest,” said his daughter Joy. Jim spent nine months on a ventilator, then more on a facial ventilator. Joy recalled, “The doctor told us he’d be lucky to ever eat pureed food again.”

For the first part of his recovery, Jim focused primarily on physical therapy, intent on getting out of the wheelchair. He joined Paraquad, a physical rehab center, to increase independence. Most people go for an hour or so at a time, but Jim would go for two hours of cardio three days a week. Two years later, he moved from his wheelchair to a walker. After that, he shifted his focus to getting rid of his trach, a breathing tube that goes directly into the throat. Despite skepticism from doctors, Jim began working with a speech therapist who helped him relearn how to swallow. “We think that what helped him trigger the swallow is called vitalstim; they put electrodes on his throat and turn the power up. It helped to get movement started,” Joy recalled.

It was slow at first, but Jim was insistent: “Turn it up more, turn it up more.” The therapist would say, “He’s crazy; the man’s crazy.” To this day, swallowing is difficult for Jim, but he is able to eat solid foods. He enjoyed his first solid meal four years after his stroke. Next up was becoming less dependent on the ventilator for breathing. He had sleep apnea, and the ventilator he was using blew the air so hard it woke him up at night. He worked constantly on diaphragm exercises so he could breathe on his own. Four and a half years after his stroke, he got rid of the ventilator. “Now he’s just using a BIPAP [a device to reduce sleep apnea],” said Joy. “Another victory,” said Jim.

Several people supporting my recovery tried to help me understand the rehabilitation journey. Comparisons to better-known situations helped. If you break your arm, you pretty much know what is going to happen. You know they’re going to put a cast on it or do surgery. You know the cast will come off in a number of weeks. With stroke, the process involves more uncertainty — what activities will help most, how long will it take, how much will it cost, and how much function can you expect to get back?

This makes stroke rehab far harder. Nobody could give me expectations, so I was constantly worried about how my progress stacked up. Was I progressing slowly or quickly? What did it mean for my long-term prognosis? How come my doctors and therapists were being so vague? “No one can say precisely which impairments will disappear completely for an individual or when they will disappear,” wrote anthropologist Sharon Kaufman.

People who are optimistic and confident that things will go well actually do better than those who are really fearful.

Because of the unpredictability, positive thinking is particularly important in stroke rehab. The journey is long and hard, and for many, if not most of us, it is never-ending. If you look at everything you’ve lost or everything you have left to do, it’s overwhelming. However, if you look with determination and positivity at the next one thing to conquer, recovery seems much more manageable. Jim Indelicato’s focus on the "small wins" ahead is critical. “I will not tell you you can’t,” said Jim’s neurologist, “because you’ll make a fool of me.”

My primary care physician, Sarah Watson, said that studies on attitudes and surgical outcomes supported this, too. “People who are optimistic and confident that things will go well actually do better than those who are really fearful,” she said. The power of positive thinking is not only mental; it leads to real physical gains in the recovery process. “I don’t think anyone thought you would get the level of language you have now,” she told me. “It is remarkable given the amount and location of the damage to your brain.”

Orienting around small wins helped me and others battle through the grind of therapy, not just in the first year but beyond. “Whether the goals are lofty or modest, as long as they are meaningful . . . and it is clear how his or her efforts contribute to them, progress toward them can galvanize,” wrote Karl Weick about small wins. They aren’t just helpful milestones; they are psychologically important. Seeing other survivors and what they have accomplished is an inspiration and a reminder to keep fighting and looking forward to more recovery.

From Identity Theft: Rediscovering Ourselves After Stroke, Second Edition by Debra E. Meyerson, PhD, and Steve Zuckerman. (Andrews McMeel Publishing, 2025) Used with permission.