Breast cancer has affected millions of women across the globe. But when it comes to who’s more likely to survive their fight with the disease, there’s one glaring disparity: the mortality rates between Black and white women.

Although breast cancer is slightly more rare among Black women, with an incidence rate that’s 5 percent lower, they have a 38 percent higher mortality rate, according to the American Cancer Society.

This has frustrated clinicians for years, but a new analysis from Susan G. Komen suggests that we’re making progress toward closing that gap. The nonprofit looked at 10 major metropolitan areas and found that in all but one region, the mortality rate for Black women had declined from 2013 to 2024.

A closer look at the data

For the report, which will be published this week to kick off Breast Cancer Awareness Month, the nonprofit analyzed data from parts of the country where the disparities in death rates and late-stage diagnosis were highest, focusing on Atlanta, Chicago, Dallas, Houston, Los Angeles, Memphis, Philadelphia, St. Louis, Virginia Beach, and Washington, D.C.

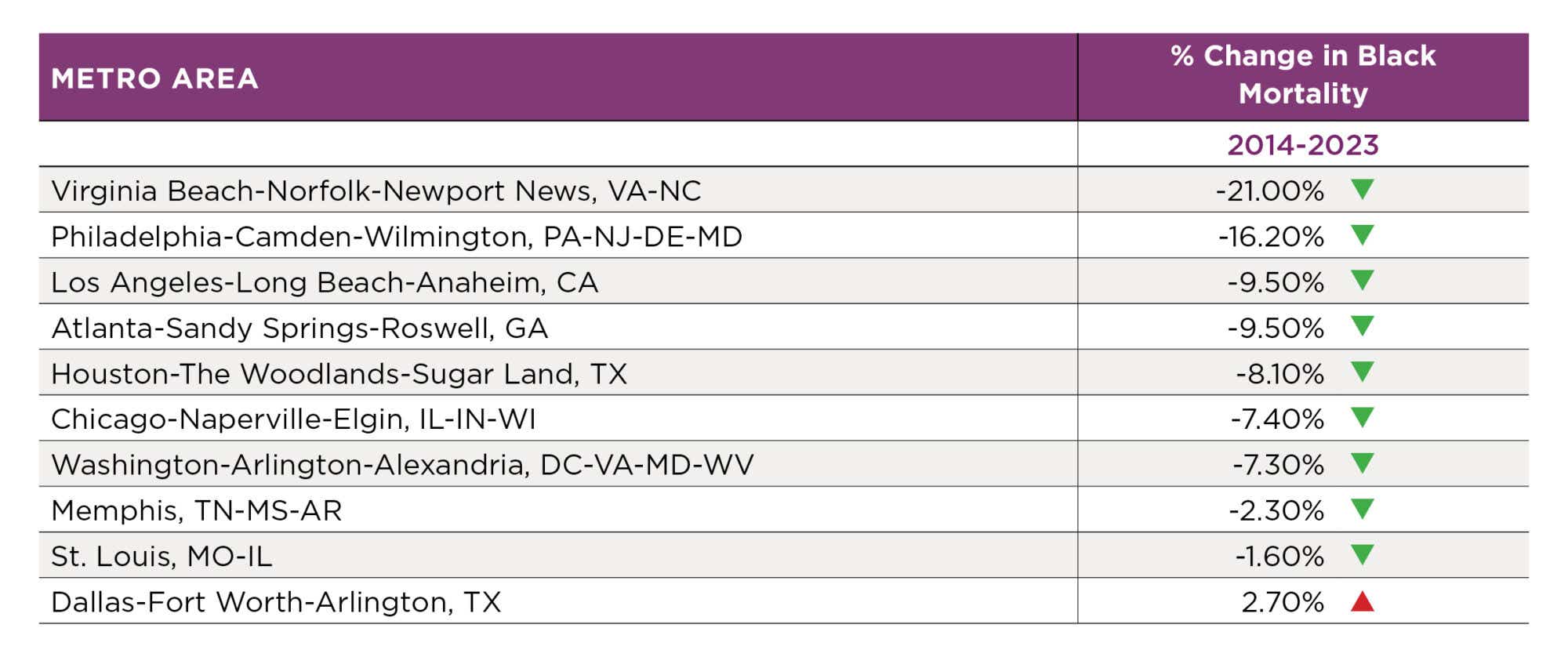

They discovered that Black mortality rates declined by double digits in Virginia Beach (-21 percent) and Philadelphia (-16 percent). Progress was more meager in areas like St. Louis (-1.6 percent) and Memphis (-2.3 percent), and nonexistent in Dallas, where the death rate increased by 2.7 percent.

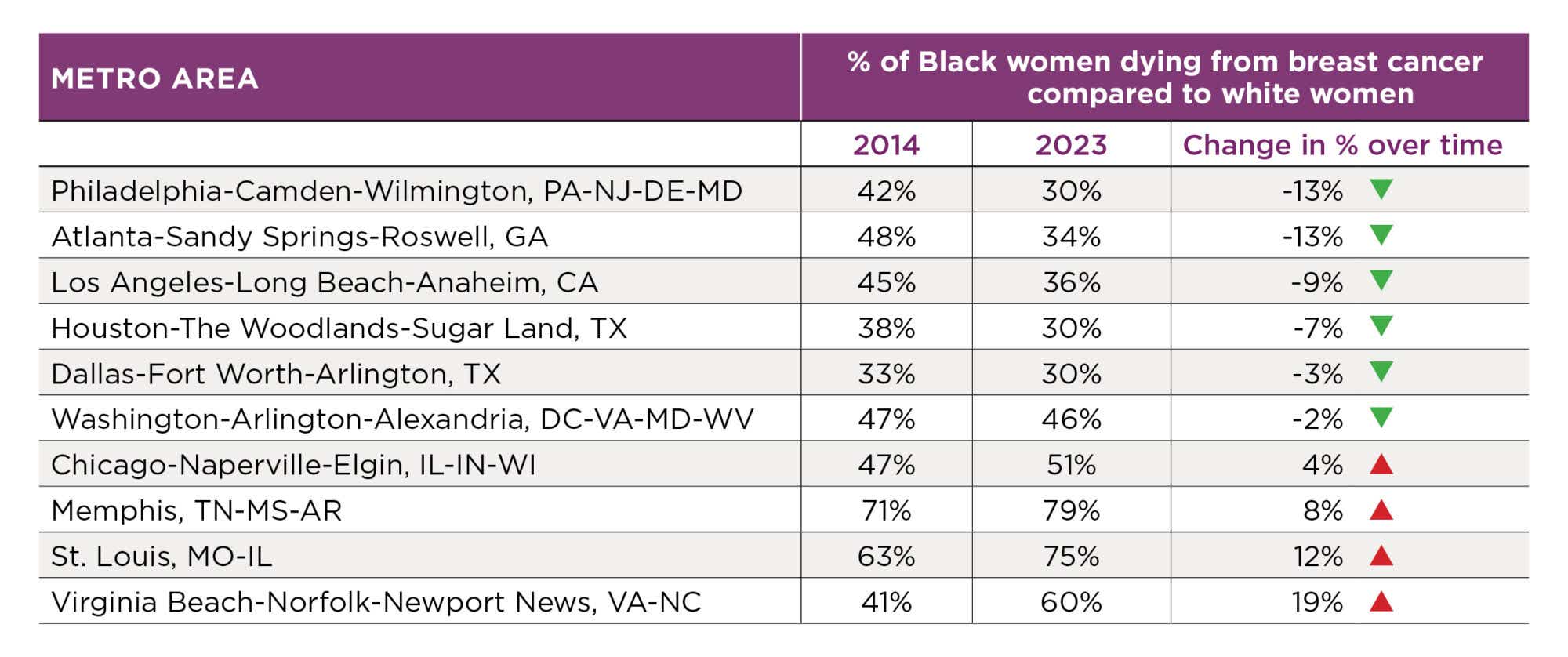

Although those numbers are mostly encouraging, in many cases that progress doesn’t translate to advancing parity between the two demographic groups. In fact, in four metros — Chicago, Memphis, St. Louis, and Virginia Beach — the gap between Black and white mortality rates actually grew. In Virginia Beach, for example, Black women were 41 percent more likely to die from breast cancer than white women in 2014, but in 2023 that number rose to 60 percent.

“We’re seeing some improvement, but not across the board,” says Sonja Hughes, MD, vice president of community health at Susan G. Komen.

Why more Black women die of breast cancer

It’s a complex issue, says Natasha Mmeje, the director of community health and outreach at Susan G. Komen. “Some of the biggest barriers are access to quality care,” whether that’s because Black women tend to live farther from top-tier hospitals or because they’re more likely to be uninsured, Mmeje tells us.

Policy plays a role, too. In Texas, for example, Medicaid coverage has shrunk, which means more women aren’t getting mammograms. “From what I’ve seen, people are still seeking care much later, when they’ve already found a lump,” Mmeje says — by which point their cancer may have progressed and become much harder to treat. That’s a systemic issue that may also have contributed to the uptick in breast cancer mortality for both Black and white women in Dallas.

What’s being done to close the gap?

One thing that seems to be working, experts say, is building breast cancer coalitions that bring together organizations like Komen, local hospital systems, and churches and other community groups, says Lorna McNeill, PhD, a professor and chair in the department of health disparities at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

One example of this is the Worship in Pink program, where Komen ambassadors educate congregations about the importance of early detection. “We’ve seen among the Black community that partnering with faith-based organizations builds a level of trust that does increase screening,” Mmeje says.

Another program that’s proved effective is Komen’s work to increase genetic testing. Black women are more likely to have triple-negative breast cancer, a more aggressive form of the disease, which can sometimes be detected through mutations in the DNA. In Houston, they partnered with MD Anderson, and in Philadelphia they worked with Penn Medicine to provide that counseling for Black women with increased risk.

“This shows that progress is possible, but there’s still more work to be done,” Dr. Hughes says.