At a recent board meeting, I ran into Stephanie Carter just as she and her co-author Jennifer had finished this piece on election grief. Besides being at the same meeting and really hitting it off, we have another important point of connection — we’re both widows: Stephanie's husband, former Secretary of Defense Ash Carter, died suddenly in 2022. We shared our respective loss experiences and the way in which any type of grief can upset your daily structure — and our firm belief that small actions can help you move forward. — Katie

If the election results put your candidates on the losing end, chances are you woke up shell-shocked the following morning. Maybe you decided the rules no longer applied and polished off leftover Halloween candy for breakfast; maybe you couldn’t eat at all. Perhaps you phoned every friend in your contact list or went instinctively inward, licking your wounds in isolation. Either way, we’re willing to bet that nothing about your post-election days have been business as usual.

As card-carrying doers who do not like the sound of the word “no,” we’re going to venture a guess that you instinctively turned to your usual action-oriented strategies in hopes they’d minimize the sting. You sought hindsight analysis to make it make sense. You read and posted missives about continuing the fight to restore a sense of agency. You pinned a bunch of quotes about “keeping calm and carrying on” to assure yourself of your resilience.

But here’s the harsh reality: We lost. In the season’s decisive match-up, we came up short. What you’re feeling? That’s grief. Loss is loss is loss. Accepting that — sitting with it and resisting the temptation to “will it away” — is your first step toward winning at losing.

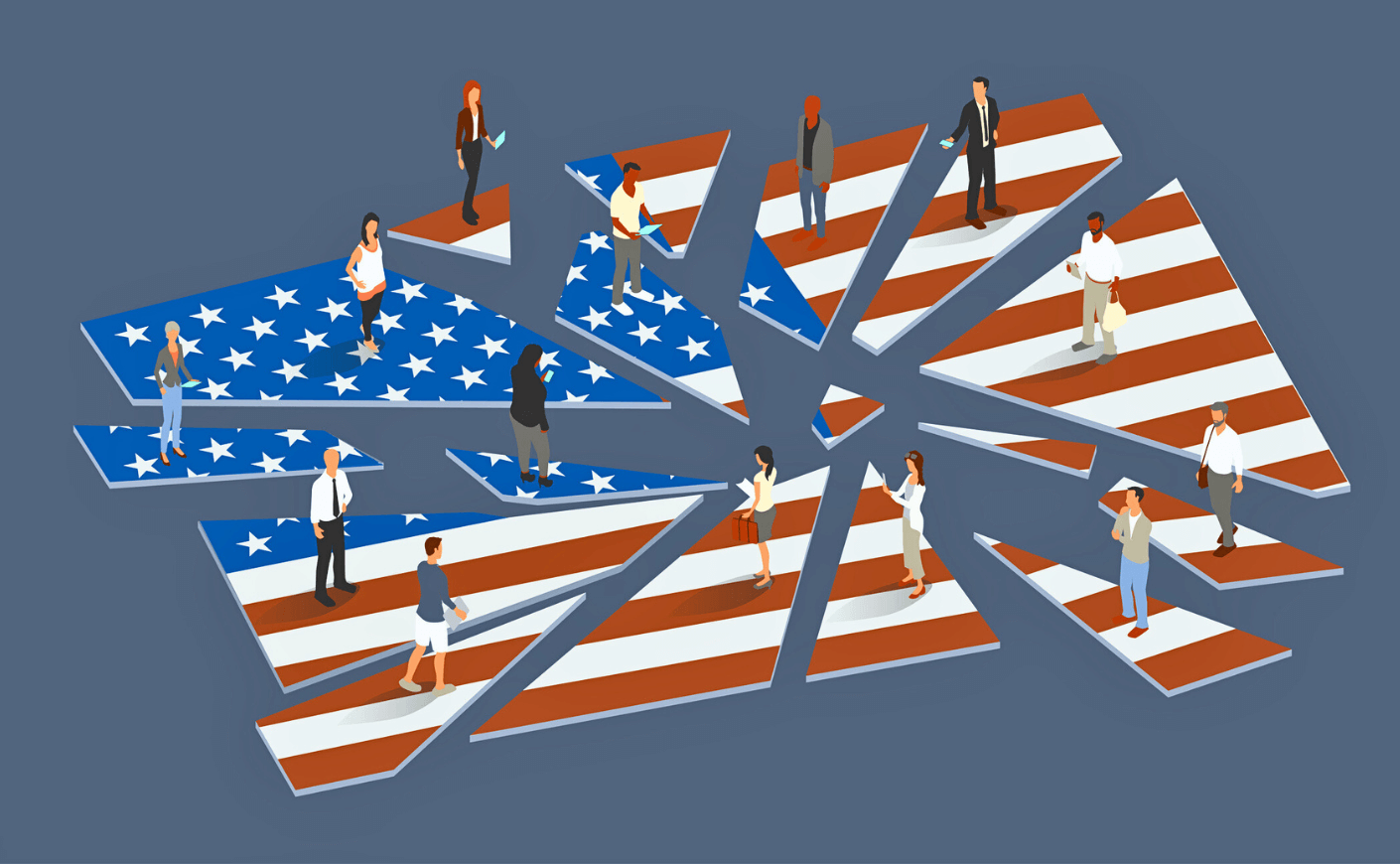

There are science-y reasons why election grief feels all-too real. As humans evolved, our very existence hinged on cohesion, forcing our ancient ancestors to resolve conflicting views for group survival. We are biologically wired to feel physical and psychological pain when we’re out of step with our pack. There is nothing like being on the wrong side of a landslide to feel a lack of social cohesion, not to mention experiencing that loss in an environment of intense tribalism. This election and its outcome did not feel like a referendum on policies as much as a pressure test of moral clarity. How, we think, could we have been so wrong about what’s right — and its ability to prevail? If the pain of that dissonance feels primal, that’s because it is.

A grief that primal cannot be intellectualized away. When catastrophic losses hit us (the sudden death of a spouse, and a child with a rare disease diagnosis, respectively), we were humbled by their leveling effects on so many aspects of our lives. Our experiences of grief were different, but the same. In the wake of these glaring losses, we began to recognize a series of earlier losses — from career loss to infertility to Covid — that we’d never acknowledged or fully processed. We began to take a more-expansive view of loss and grief, seeing it anew as an everyday phenomenon that exists virtually all around.

Why do we tend to be so myopic when it comes to recognizing loss and grief? For one thing, as a society we’ve subconsciously absorbed a sense of comparative suffering; we brush off incidental and less acute losses by reasoning that other people have it worse. This may at times be true — and we should always maintain gratitude for the good fortune we have — but it is not helpful. Loss is not a zero-sum game; there is no grief Olympics. When we fail to acknowledge any loss, we can almost count on grief popping back up like a Whack-a-Mole, shape-shifting to another corner of life. That’s why we’re giving you a permission slip to sink into election grief for a little while, and absolving you from the urge to fix it.

To be clear, we’re not suggesting wallowing, interminable couch surfing, or a complete loss of agency; after all, a loss of agency is at the core of election grief. Many of us believed in a cause and were heavily invested in a certain outcome. There is a yeoman’s work ahead, and that will come in due time. But our first steps forward must acknowledge — and align with — the grief state we’re in. We’re talking micro-actions, not mountains moved. New rules for a new field.

Essentially, take all your can-do instincts and do the inverse of what they’re telling you.

Watch your information intake

People want an explanation for the unexplainable, which is one reason we were each asked whether vaccines were behind our loved ones’ health misfortunes (true story). We live in an uncertain world, and information proliferation can falsely confer a feeling of control. While this may be a short-term elixir, ultimately it’s no cure. Ad nauseam analysis cannot tell us definitively why our candidates lost, any more than our family members’ vaccine status foretold their afflictions. It’s important to think of the economics of information providers and how sensationalism is backed up by some serious financial incentives. The key is to avoid conflating “informed” with “information.” Choose wisely about what you engage with, when, and consider an information diet — even an intermittent fast.

Build your social — not social media — capital

While it’s tempting to duke it out with someone on their Facebook feed, now is a good time to mute social media and instead re-clarify your IRL social connections. We know that a third or more Americans report feelings of isolation and loneliness, and that those dynamics can quite literally hurt your health. At the same time, there are real people downstream of policy decisions who may end up marginalized or even unsafe. Committing to reaching out — to fostering true connection and filling vital needs for others — is a win for all, and there is real community to be found in doing so. Favor realistic long-term efforts over a post-election grand gesture; nothing is more deflating than watching a well-intentioned but unsustainable action fade into the ether.

Act hyper-locally

Our national politics gets the “main character” treatment, but it’s the local policy decisions that can have the greatest bearing on our lives. Fortunately, we can also make a more-measurable impact at the local and state levels when it comes to the issues that keep us safe and prosperous: from policing and educational priorities to environmental standards. So rather than lament what may be happening nationally, commit to entering a more proximal arena by engaging with an aspect of local government that piques your interest. Who knows? Maybe you’ll be on the ballot the next time around.

Stay curious

Maybe you wish you knew enough to solve global problems, but what’s keeping you from a learning opportunity at your fingertips? Not only does learning something new increase your self-confidence and sense of progress, it fosters a growth mindset, associated with higher levels of resilience. We’re not suggesting that a sourdough starter will save the day — it certainly didn’t keep Covid away — but a good dose of mastery went a long way to restoring our pandemic sense of self, and there’s a good place for it now, too.

Even ChatGPT itself could not tally the number of “unprecedented” references in the news since November 5, but it also acknowledged that the term has been used so frequently to describe all manner of crises that it no longer has oomph. Every loss, by nature, is to some degree unprecedented. The key to winning at loss in any form is to take cues from the universal grief playbook: “take the L,” reset expectations for yourself and others, and find the micro-actions that move you forward.

Stephanie Carter is a writer and the wife of late Secretary of Defense Ash Carter. Jennifer Handt is a writer, special needs mother, and rare-disease advocate. Together, they're developing a book about moving forward after loss.