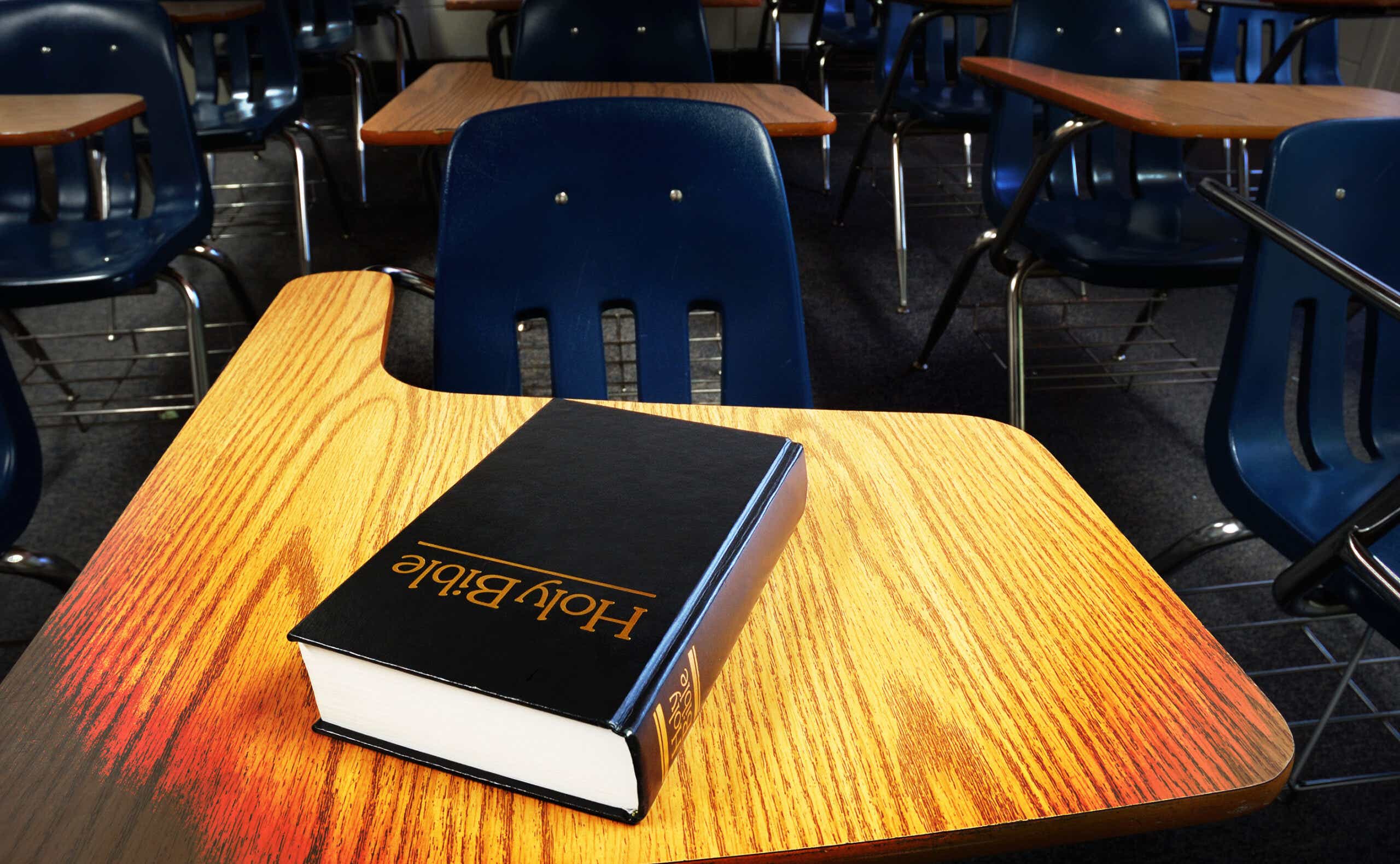

If you grew up going to public school in the U.S., you probably remember your classroom being decorated with cheesy art, animal pictures, and maybe some innocuous class rules (“don’t speak without raising your hand,” “keep your hands to yourselves,” etc.). If you went to a non-secular school, you might’ve seen similar art, only with much more of a focus on Jesus and class rules that referenced Bible passages. Now the gap between the two types of education could be closing in certain states across the country, as conservative lawmakers push administrators and school to incorporate more religion in the classroom.

In June, Louisiana became the first state to require the Ten Commandments to be displayed in public school classrooms as part of a broader effort “to address policy issues from a biblical worldview.” Lawmakers in other states have introduced similar legislation, including Arizona, Georgia, South Carolina, Utah, and West Virginia.

Proponents argue that religious texts have historical and moral value for young students. While lawmakers in Texas have proposed offering Bible elective classes in high schools, Oklahoma has started incorporating scripture into the curriculum alongside other class material like the Declaration of Independence. However, this has prompted concerns from some advocates, who say that such mandates violate the First Amendment’s establishment clause, which states that, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.”

But is public education really becoming more like Sunday school? Here’s a look at where state legislators are calling on teachers to lean into religion and its broader implications.

The debate over religious texts in public classrooms

Oklahoma recently joined Louisiana in becoming the latest state to integrate the Bible “as an instructional support into the curriculum” for grades 5 through 12. Oklahoma State Superintendent Ryan Walters laid out how school districts should add it to their lesson plans and how it should be taught for different grades.

“This memorandum and the included standards must be provided to every teacher, as well as providing a physical copy of the Bible, the United States Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, and the Ten Commandments as resources in every classroom in the school district,” his guideline reads. “These documents are mandatory for the holistic education of students in Oklahoma.”

Amid backlash about the controversial mandate, Walters argued that the religious text is an “indispensable historical and cultural touchstone.” But can he force educators to teach it? The Oklahoma Attorney General’s Office has said that state law already allows for the Bible to be taught in classrooms, but that doing so is a district-by-district decision. Still, the superintendent has threatened teachers by saying they could lose their licenses if they don’t follow his directives.

“This rhetoric from Oklahoma State Superintendent Ryan Walters doesn’t help the morale of our less than 40,000 teachers now in Oklahoma — and they’re dwindling by the minute,” Jena Nelson, 2020 Oklahoma Teacher of the Year, tells Katie Couric Media.

Despite Walters’ threats, at least eight of Oklahoma’s largest school districts — including Norman, Moore, and Stillwater — have publicly said they won’t integrate biblical teachings into the curriculum, which some fear would limit teaching on LGBTQ people and racism. One parent in Mayes County even sued him over the mandate.

Religious freedom organizations have also spoken out: Rachel Laser, president and CEO of Americans United for Separation of Church and State, tells us that while she doesn’t oppose teaching religion as a part of history, she objects to teaching the Bible as truth or “core values.”

“Public schools can teach about comparative religion and the influence of the Bible and other religious texts on topics such as history and civilization,” says Laser. “But studies have repeatedly shown that public schools struggle to teach about the Bible without preaching from the Bible — to educate without indoctrinating students.”

How else are school districts incorporating religion?

Teaching the Bible isn’t the only method through which legislators are trying to insert religion into classrooms. For instance, Texas and Florida allow public schools to hire chaplains in mental health roles. (In case you’re not familiar, this type of clergy member is seen as a representative of a religion and can provide spiritual guidance and conduct religious ceremonies like weddings or funerals.)

Now, at least half a dozen other states are considering similar legislation with varying degrees of success. Chaplain bills were approved in Utah and Louisiana but died in Indiana.

Advocates believe chaplains could help provide additional support to kids in need. Meanwhile, opponents feel their nonscientific counseling methods could actually exacerbate the mental health crisis because these chaplains aren’t typically trained or certified to provide educational or counseling services to youth. Using these untrained religious leaders might suggest that serious conditions like depression can simply be prayed away.

These proposals have received surprising pushback from even religious leaders themselves: More than 170 Texas chaplains signed a letter opposing school chaplain programs, calling them an “affront to the religious freedom rights of students and parents as well as church-state separation.” They also noted that their ministry is “not a replacement for school counselors or safety measures in our public schools.”

Some Christian lawmakers, like Texas State Rep. James Talarico, have also railed against this infusion of religion in public life. “I’m a Christian, but I know the most dangerous form of government is theocracy — the only thing worse than a tyrant is a tyrant who thinks they’re on a mission from God,” he tells us.

Ultimately, local school boards in Texas received thousands of phone calls demanding they reject the chaplain proposal — and they listened. Rep. Talarico says 25 of the state’s biggest districts, including Houston Independent School District and Dallas ISD, rejected replacing school counselors with chaplains.

What’s driving this push?

These types of bills are mushrooming in an era when religious rights have been expanded under the right-leaning Supreme Court. Even as the U.S. becomes more religiously diverse and secular, the court has handed down rulings in favor of conservative Christians seeking more voice in public life, and 2022 marked a turning point in these wins.

During this time, justices backed Maine parents looking to use taxpayer dollars for religious school tuition and sided with a high school football coach who lost his job because of his post-game prayers at the 50-yard line. They also unanimously agreed to let a Christian group fly its flag over city hall in Boston, and during oral arguments for this case, Justice Neil Gorsuch even wondered about the “so-called separation of church and state.”

University of Virginia law professor Rich Schragger believes the high court has emboldened Republican-led states to “adopt aggressive pro-prayer and pro-Bible positions in the public schools,” which he says could be a prelude to bringing school prayer back altogether.

“Mandated Bible teachings or readings that treat those religious texts as moral codes are clearly unconstitutional under current Supreme Court case law,” Schragger tells us. “But the U.S. Supreme Court has, in recent cases, indicated a willingness to revisit settled constitutional law and permit a much wider range of religious expression in the public schools.”

Some lawmakers believe the rise in Christian nationalism, which seeks to merge Christianity with American identities, may also be to blame for this push for religion in schools, and they worry it poses a much larger risk.

“Christian Nationalism is a threat to democracy,” Rep. Talarico tells us. “They’re trying to convince us that our neighbors are to blame for our alienation; that domination can calm our anxieties; that democracy is not the solution, but the problem.”