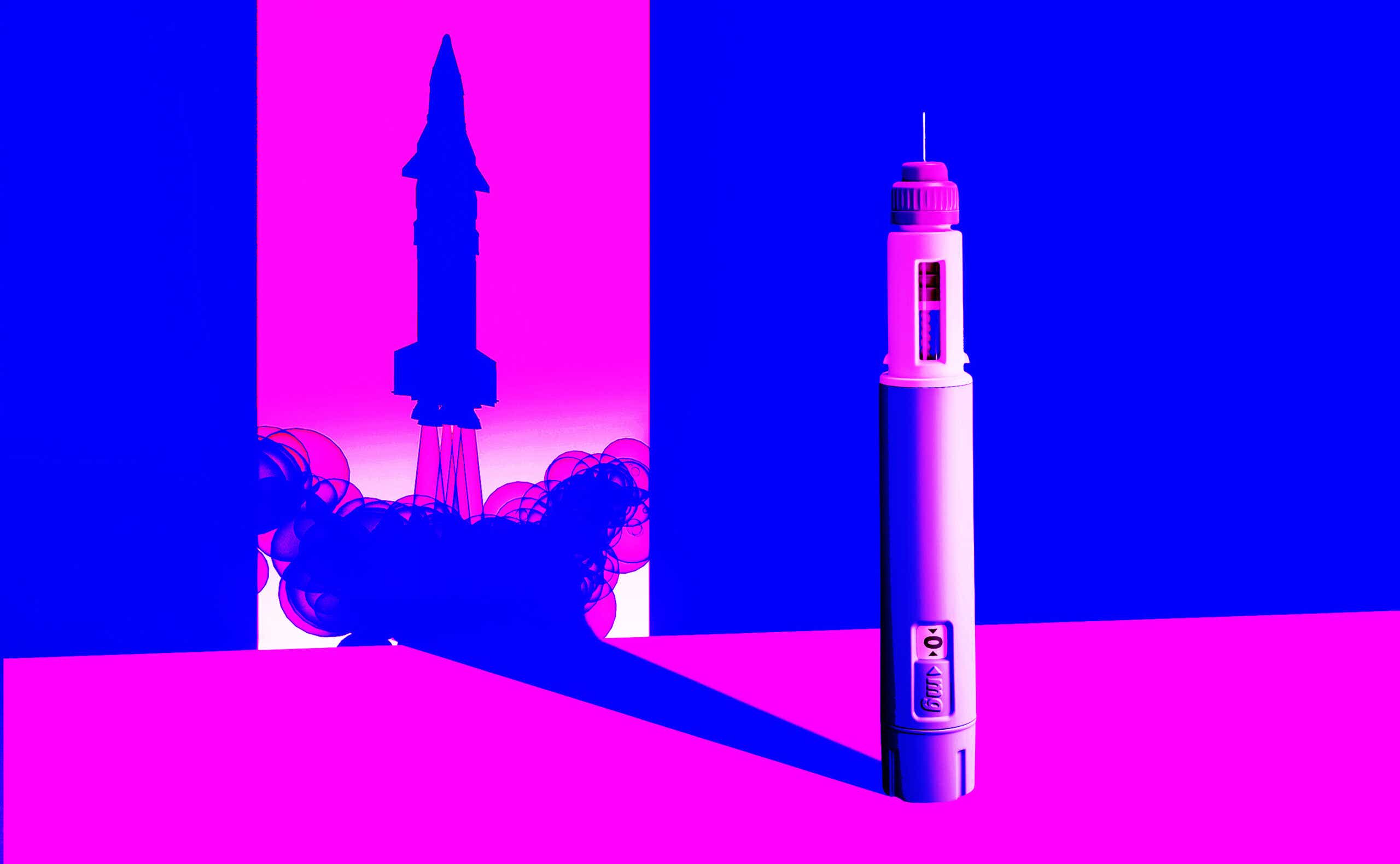

If you were conscious in the 90s, you probably remember crazes like Tamagotchis and the Spice Girls — and the frenzy around fenfluramine/phentermine, aka fen-phen, the drug combo that was touted as a “miracle” cure for obesity. (That is, before it was linked to serious heart and lung issues). Now there’s a new-and-improved — in theory — weight loss drug on the block. Well, technically it’s a diabetes drug that’s being used off-label for weight loss: Yes, we’re talking Ozempic, the medication on everyone’s lips (not literally — it’s an injection) that’s taking inches off everyone’s hips.

Ever since winter 2022, journalist Johann Hari — and, most likely, many of you — has noticed people becoming “clearer and sharper,” aka thinner. He originally thought it was due to a renewed cultural obsession with Pilates, but the cause turned out to be much more complex: Semaglutide, better known as Ozempic, started making headlines for its impact on weight loss, causing a ton of controversy in social circles and Hollywood alike. Was it safe? Effective in the longterm? Would it tear down the body neutrality movement many had been working so hard to build up? And if it could lower the risk of health conditions caused by obesity, Hari wondered, was it worth it?

As Hari learned about Ozempic’s effect on weight and health, he was tempted to try it himself. So he did. As he experienced some of the drug’s infamous side effects, he dove deeper into the science behind it. The result is his book Magic Pill: The Extraordinary Benefits and Disturbing Risks of the New Weight-Loss Drugs, focused on the impact this new generation of weight-loss medications will have on society.

Wondering if Ozempic is truly the miracle drug we’ve been promised? How will we use it in the future? And should you try it yourself? Read on for Hari’s thoughts on this revolutionary science, why he compares its impact to that of the smartphone, and whether he plans to stay on the medication himself.

Katie Couric Media: What led you to start writing about Ozempic?

Johann Hari: 50 percent of Americans say they're “interested” in taking weight-loss medications, according to a recent survey. It’s going to transform the culture all around us in fascinating and complex ways, for better and for worse.

Obesity causes a huge array of illnesses, more than 200 known diseases and complications. I knew that a drug that could reduce or reverse obesity could have huge health benefits, but I also thought, Wait a minute, I've seen this story before. Every previous diet drug presented as a “miracle” always had to be pulled from the shelves after causing some kind of disaster. I thought, Can it be as good as it seems? Is there really such a thing as a free lunch? Though I guess with Ozempic, it would be a smaller free lunch.

You started taking Ozempic in 2023, following years of battling with your weight, and because of concerns about your health and family history. What does it feel like to be on it?

I'll never forget the second day I took the drug: I woke up, I was lying in bed, and I felt something strange. I couldn't figure out what it was for about five minutes, and then I realized I had woken up and I wasn't hungry. That had never happened to me before — I used to be woken up by raging hunger. So I went to this diner near where I live, and I ordered what I used to order every morning for breakfast: a big chicken roll with loads of mayo in it. I’d eat that every day and still be hungry at the end of it. But this time I had three or four mouthfuls, and I felt full. I just didn't want anymore. And that was how I was from then on: really full, really fast.

What was happening exactly? How does Ozempic work?

These drugs massively boost your sense of satiety. Your pancreas naturally produces a hormone called GLP-1, which is one of the natural signals in your body that say, “Hey, you've had enough. Stop eating.” It's the brakes on hunger, basically. However, natural GLP-1 only stays in your system for a few minutes, whereas Ozempic is an injection of an artificial copy of GLP-1 that sticks around in your system for a whole week. So I lost a huge amount of weight, 42 pounds in a year. There were all sorts of benefits, and for the first six months, I was getting what I wanted — I was losing loads of weight. But I didn't actually feel better. If anything, I felt slightly worse. My emotions felt quite muted. I wondered if it was connected to the fact that some doctors are warning these drugs may cause depression, or even suicidal feelings, in some people. It wasn't that bad for me, but I was feeling muted.

Seven months in, I was in Las Vegas, and I went to this branch of KFC that I've been to a thousand times, and did what I would've done before I was on Ozempic: I ordered a bucket of fried chicken. But this time I sat there, had one of the chicken drumsticks, and realized I couldn't eat the rest. I realized that since I was a small child, I had primarily used food to calm myself down, comfort myself, numb my feelings — and you just can't do that on these drugs. I thought, Oh, I'm just going to have to feel bad.

These drugs radically interrupt your eating patterns, obviously with huge benefits. But they bring to the surface the underlying psychological drivers of the way you eat. That can be a good thing because if [those emotions] come to the surface, you can then find better ways to deal with your feelings than Colonel Sanders. But that was, for me, a bumpy and difficult transition.

After all your research and writing, what do you think is the future of Ozempic and similar weight-loss medications? Do you think they’re miracle drugs?

There are three ways these drugs could be magic, hence the name of my book, Magic Pill. The first is the most obvious: They could solve the problem of obesity so quickly and so swiftly that it feels like magic, and there are days when it feels like that. My whole life, I've been overweight and addicted to junk food, and now I inject myself in the leg once a week, and I've gone from eating 3,200 calories a day to 1,800. It feels like magic.

The second way Ozempic could be magic is much more disturbing. It could be like a magic trick that conjures an illusion, like a magician who shows you a card trick while secretly picking your pocket. It could be that the 12 big risks of these drugs that I identify in the book, which are separate from the common side effects like nausea, are so severe that they undo the good of the drugs and therefore screw you over. That’s a significant possibility for some people.

The third way Ozempic could be magic is I think the most likely. Think about the stories of magic that we grew up with as kids, like Aladdin: You find the lamp, you rub it, the genie appears, you make a wish, and your wish is granted. But your wish never comes true quite the way you expected — it always has unpredictable effects. I think we're already seeing many unpredictable effects, some positive and some negative.

Barclays Bank commissioned an analyst named Emily Field to research these drugs to guide the bank’s future investment decisions, and she came back and said, “If you want an example of what these drugs will do, you've got to compare them to the invention of the smartphone, in terms of how they're going to affect the economy and the society.” And I think she's right.

What impact do you think the success of Ozempic will have on the body-positivity movement?

The worst moment for me in the writing of the book was maybe four or five months in, when I was FaceTiming with my niece Erin who’s 19, the baby of my family, and the only girl. She was teasing me in a flattering way, saying things like, “I never knew you had a neck. I never knew you had a jaw,” and I was kind of preening. And then she said, “Will you buy me some Ozempic?” And I laughed because I thought she was kidding. She's a perfectly healthy weight. And then I suddenly realized she wasn't joking, and I thought, Oh shit, have I undermined every message I've been trying to give her since she was a little girl about valuing herself?

We've got to distinguish between two groups here: Overweight or obese people who are taking these drugs to get down to a healthy weight and still incurring a significant amount of risk but also experiencing a lot of benefits. Then there are people who already have a healthy weight who are taking them to be skinny or super skinny. Now, I don't judge anyone — in this culture, women, in particular, are made to feel like shit about their bodies no matter what they do. But they're taking all the risks for only an aesthetic benefit.

Obesity does, on average, harm your health in quite significant ways, and it can also lead to bullying and cruelty. Shelley Bovey, who basically introduced body positivity to Britain, pointed out to me that if you love someone who's obese, you probably want to protect them from both cruelty and the health harms of obesity.

Some experts say that Ozempic might have an impact on addiction treatment — how do you see that working?

I interviewed the leading scientists in Sweden, at Penn State University, and at Florida State University, and what we know is that in animal studies, these weight-loss drugs also massively reduce the use of alcohol, fentanyl, heroin, and cocaine across the board. We don't yet know whether that functionality will transfer to humans, but it's possible. The most optimistic scenario for these drugs, and it's speculative at this point, is that actually they're not weight-loss drugs, but ones that boost self-control and self-regulation across the board. The effects on humans are still unclear.

What about those with or recovering from eating disorders? Do you think it could exacerbate or even cause eating disorders?

This is my single biggest worry of the 12 big risks that I go through in the book. Dr. Kimberly Dennis, one of the leading eating disorders experts in the country, said to me, “These drugs are rocket fuel for people with eating disorders.”

Anyone who's known anyone with an eating disorder knows that they're in a battle. There's the part of them that wants to starve themselves for complex psychological reasons related to our dysfunctional culture and the pressures we put on women and girls, and then there's the biological part of them that wants to survive, eat, and keep the body going. And what these drugs do, if you take them in high enough doses, is just amputate your appetite. So they empower the psychological part against the biological part. And my worst nightmare for these drugs is that, in addition to all the benefits for people like me who were obese, there will be an opioid-like death toll of young girls who take these drugs and kill themselves, who would not have been able to starve themselves to death without them.

Back in the 90s, there was a diet drug called fen-phen that huge numbers of people with eating disorders took, and it caused all sorts of health problems. These new drugs are much more powerful than the ones people were taking then. But there are things we can do about this. As Dr. Dennis explained, at the moment, pretty much anyone can go on Zoom and get these drugs. She argues you should only be able to get them from an in-person appointment with a doctor who actually examines you and is trained in spotting eating disorders. That won't totally prevent this crisis, but it will massively reduce it. We need to be lobbying for that urgently.

What are some of the big things we don't know about these drugs?

We know that they reduce your risk of heart attack or stroke by 20 percent, if you started with a BMI higher than 27. They also reduce inflammation, which is one of the worst and most devastating effects of obesity — inflammation within your body can screw up your body's immune responses.

When you talk about the safety of these drugs, generally experts say, “We know quite a lot about the safety — diabetics have been taking them for 18 years now.” But other scientists say, “If we're going to base our confidence in the safety of these drugs on the diabetics, let's dig more deeply into the diabetics.” So, for example, one professor found that these drugs boost your thyroid cancer risk by between 50 and 75 percent, which is very alarming if he’s right — he’s been contested. That doesn't mean if you take the drugs, you have a 50 to 75 percent chance of getting thyroid cancer. If he’s right, it means that whatever your thyroid cancer risk was at the start, it goes up by 50 to 75 percent. Thyroid cancer is relatively rare — 1.2 percent of people get it in their lifetime, and 84 percent survive. Nonetheless, that is alarming.

Other people say, “Well, you've got to compare that risk to the cancer risk just from being obese.” Sadly, obesity is one of the biggest causes of cancer in our society.

So there are real risks of these drugs, and there are also real risks of continuing to be obese. That's why I think people need to really go down the list of the risk factors and see which ones apply to them before starting these medications, because there is no simple, one-size-fits-all answer.

What do you think more people need to understand about Ozempic?

If you're overweight or obese, you're not a failure. I felt like such a failure when I was obese. What you are is an entirely typical product of our times: 42 percent of Americans are obese, and 70 percent are overweight or obese. We’re living in a trap that we did not design, and at the moment, we're being offered a risky and rusty trap door. Some people will want to go through that door and some people won't. I respect both sets of decisions, and I think my book will help people make that decision in an informed way. The most important thing we need to do is dismantle the trap. Japan never got into it — they didn't allow the processed food industry to fuck up their kids. But those of us in the trap now have to make a decision.

I’ve decided to continue taking the drugs because there's so much heart disease in my family. For me, the benefits of reducing heart disease outweigh the risks, and a lot of the risks don't apply to me. But I think everyone needs to make this decision for themselves. I hope my book provides a way for people to pause and think deeply about this drug that’s about to profoundly transform our culture.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.