What would Tom Hayden do?

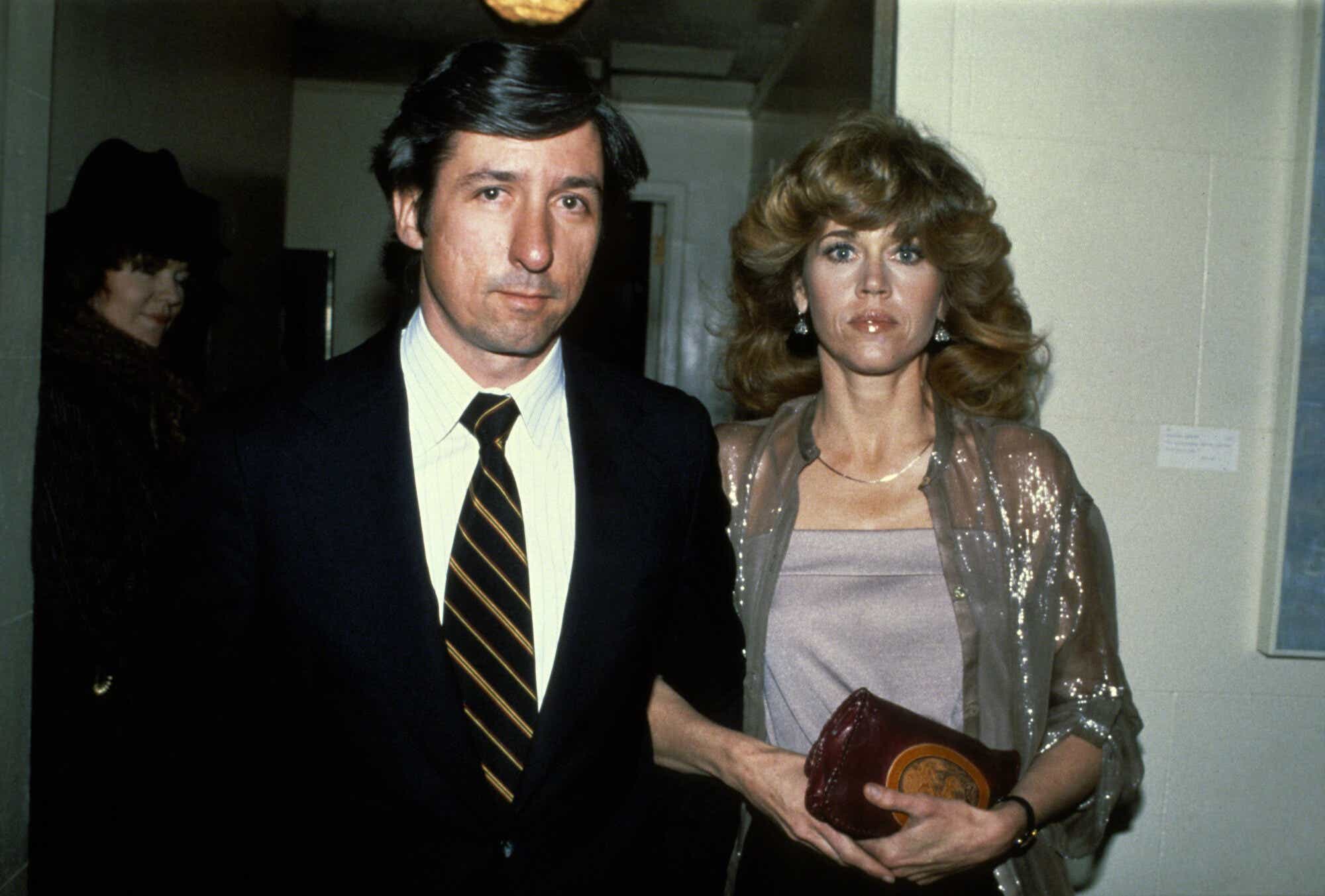

It is a question many are asking, especially those who compare — and almost nostalgically recall — the campus protests of the sixties. As co-founder of Students for a Democratic Society (who later became famous as Jane Fonda’s husband), Tom Hayden snuck into Columbia University in April 1968 to take part in the occupation of the university’s Mathematics Hall.

The NYPD eventually arrested him along with hundreds of other students and older activists. These experiences convinced Hayden and many others on the New Left that they had to “bring the war home” during the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago. (Does the Chicago Seven ring a bell? Hayden and the others were later acquitted of conspiracy to incite a a riot in one of this country’s most celebrated trials.)

As we head into another election convention season — including one in Chicago — much of this does engender comparison. New York University historian Michael Koncewicz is currently writing a book on Tom Hayden, and told me, “I believe he’d hesitate to argue that 2024 is a carbon copy of 1968. Still, he would recognize the echoes, especially when identifying the links between those who had tried to erase the Vietnam War from our collective understanding of the sixties, and ongoing efforts to do the same with Israel’s war on Gaza.”

For those of us who lived during Hayden’s time, the comparisons to previous protests also rankle. I recently joined my husband, an alum, at the University of California, Berkeley, for an event there. We were immediately in the presence of thousands of protestors. “I guess it feels like nothing has changed,” I said. “Not true,” said my husband, “in those days we were all on the same side.”

The war our generation was protesting, of course, was personal: American sons and brothers (mine managed to win a court case as a conscientious objector) were being drafted and asked to put their lives on the line. The concept of “dis-investing” in anything militaristic remains relevant, if backed by real facts and numbers. My father started an organization called Business Executives Against The Vietnam War, which proved war was not, as originally believed, good for business. (Yes, I grew up in a home where I was not even able to participate in the famed generation gap. Every time friends asked if I would be going to the anti-war moratorium in D.C, I had to confess, “I guess so. My dad is paying for it.”)

Tom Hayden — whom I knew in California and who died in 2016 — stepped away from revolutionary politics later in life. But as Koncewicz reports, “He never retreated from believing that wars, and other forms of official violence, were to blame for social disorder.” Decades later, Hayden returned to Chicago, this time as a delegate and state senator from California. Yes, he had gone into the system to try to change it. Unlike some of his contemporaries, he believed that our nation’s leaders and institutions — not student protestors — were responsible for the chaos of 1968. Chancellors throughout the country may be learning that as we speak.

Those educators are trying to tell their students that social change can only come about through the processes of negotiation. We hope that the students now — as then — have discovered that barricades and tents are only the beginning. Talking to one another, respecting other’s differences, but all uniting to oppose sanctioned murder, must emerge.

In truth, many question whether today’s on-campus activists have it in them. Carol Gluck, Columbia’s just-retired and hugely respected history professor says that in all her decades of teaching, “this generation is the most anxious, the most fragile.” Many, of course, never got a normal high school experience due to Covid. Giving up large farewell ceremonies is a painful price to pay. But as my husband half-jokes, “we never had a graduation the whole time I was at Berkeley.”

So, what would Tom Hayden do in 2024? According to his current biographer, “he would privately critique some of the messaging and tactics of today’s demonstrators, but he would applaud their ability to shift the nation’s collective discussion on Israel and Palestine.” He might encourage his own contemporaries (those still with us) to build alliances with younger organizers, not to mention taking on leadership roles in their own communities. Hayden truly believed that social movements could bring about historic change. But he also knew you had to get inside where the real decisions were made.

This article was originally published on West Side Rag. Michele Willens recently published a book of essays called From Mouseketeers to Menopause.