Wilhelm. Hugo. Emma. Even decades after their deaths, hearing the names of her three youngest children still makes Helene Cederroth’s face light up. “It’s wonderful to talk about them,” she says with a smile. “They were so full of life.”

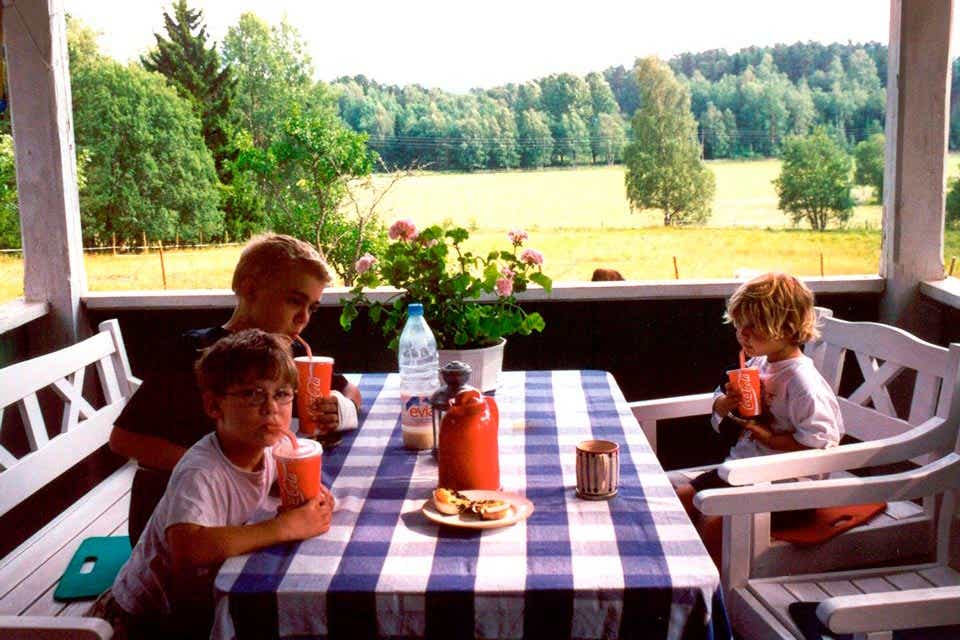

Wilhelm, Cederroth’s oldest son, loved animals. In the summer, he would make tiny “animal hospitals” in the backyard for injured crickets. Hugo loved trucks. “We moved to a farm in our home country of Sweden, where we had a small horse. Hugo used to pretend it was a truck,” recalls Cederroth. Emma, the youngest, was the bright-eyed mischief-maker in the family: “She would always try to make us laugh by pulling little pranks,” smiles Cederroth.

Two years after she welcomed a healthy baby girl, Cederroth became pregnant with a son. They named him Wilhelm. It wasn’t long before Cederroth noticed something different about their new baby: “He would make these strange movements, but I didn’t know why. I didn’t know anything then,” she recalls. At four months old, Wilhelm was diagnosed with epilepsy, and put on medication. Cederroth noticed another concerning symptom in her son: His stomach was often swollen, causing him pain. After running some blood tests, doctors determined there were no additional issues.

When Cederroth became pregnant with her son Hugo in 1991, she was worried. “The doctors all told me Wilhelm’s condition wasn’t fatal, and it wasn’t genetic,” she remembers. “And I believed them.” But during her third trimester, Cederroth sensed something was wrong. “I felt a strange fluttering in my stomach, and I knew in my heart he would be like Wilhelm.” Doctors told her she was just feeling the baby hiccupping, and she had nothing to worry about, but when Hugo was just six hours old, he had his first seizure. He was also diagnosed with epilepsy.

Cederroth was convinced this wasn’t just epilepsy, so she sought out the best geneticist in Sweden. “You have to remember this was almost 30 years ago,” says Cederroth.”We were being treated at one of the best hospitals in the world, and they couldn’t give me another diagnosis. It got to a point where they didn’t trust me — they said it was all in my head.”

A few years later, Cederroth became pregnant with her fourth child, this one a girl. She was terrified. But doctors assured her that since she already had one healthy daughter, her baby would be fine — this was clearly a condition that only impacted boys. Then, in her third trimester came the fluttering. “Everyone was telling me she was healthy,” says Cederroth, “And I wanted to believe that.” So she ignored the sensation. When Emma was born, Cederroth’s worst fear was realized: Her daughter also suffered from the unknown condition. “I think at first I was in denial,” she remembers. “We got out of the hospital as quickly as possible, because if we didn’t acknowledge it, maybe it wasn’t real.” Just as Cederroth arrived home with their infant, Emma had a seizure. They immediately turned around and went back to the hospital, where Emma was also treated for epilepsy.

All three children suffered from the same stomach condition, and Wilhelm also had particularly bad asthma. The family moved to the countryside to make their children more comfortable. The Cederroth parents settled into a routine, dealing with the symptoms of their three youngest children, and trying to give them as normal of a life as possible.

When Wilhelm turned 12, they noticed some concerning changes. “He had always loved school, but suddenly he couldn’t focus on his work anymore,” she remembers. They chalked it up to the exhaustion of being in and out of the hospital. Soon, he forgot how to ride his bike. Then one day, his grandmother visited, and Wilhelm didn’t recognize her.

“That’s when we brought him back to the hospital, and the doctors diagnosed him with dementia,” says Cederroth. The Swedish medical community had no idea what was happening to Wilhelm, so Cederroth began looking for help abroad. She took Wilhelm to specialists in London, Vienna, and the US. Some doctors proposed theories, but nobody had a firm diagnosis — or cure — for her son.

“I couldn’t believe this was happening,” says Cederroth. “I knew this was probably going to be the future for Hugo and Emma, too.” Wilhelm continued to mentally and physically deteriorate for four more years. In 1999, he passed away at just 16 years old.

After Wilhelm died, Cederroth fell into a depression. She remembers feeling a deep sense of guilt: “How can you live, as a mother, when you can’t keep your own children alive?”

She was particularly haunted by her son’s last days. “He had been so afraid to die,” says Cederroth. “And at the time, I wanted to go with him. I couldn’t stand the thought of him being alone.” But Cederroth knew she needed to care for her other three children, though as she recalls, “part of me felt like I was dead already.”

To help cope with her grief, Cederroth connected with the mother of a girl named Victoria, who had also recently passed away and was just a few years older than Wilhelm had been. “I told her about how scared I was that Wilhelm was alone,” says Cederroth, “and this woman said to me, ‘Don’t worry, Victoria will take care of him.’ That was a great comfort to me.”

After Wilhelm’s passing, the Cederroths steeled themselves to cope with Hugo and Emma’s declining health and vowed to make the remainder of their lives as magical as possible. “Emma had always wanted to go skiing,” says Cedderroth. So she made it happen. “She was so happy,” remembers Cederroth. “I’m so glad we were able to give her that.”

Cederroth now felt a growing sense of urgency to find a diagnosis, and hopefully a cure, for her two ill children. So in 1999, she and her new husband Mikk founded The Wilhelm Foundation, aimed at finding a cure for undiagnosed diseases in children. Cederroth began fundraising to find answers about why her children were sick, doing interviews with local newspapers and meeting with journalists. They began channeling their grief into this new project…but then Emma took a turn for the worse.

Soon after Wilhelm’s funeral, Emma developed a viral infection, and her health began rapidly declining. In December, Swedes celebrate a holiday called Saint Lucia Day, a festival where children dress in white and adorn themselves in lights. “Emma loved Saint Lucia Day,” says Cederroth, “And we knew she wasn’t getting better. So we celebrated it for her in the summer.” Soon after, just about a year after Wilhelm’s death, Emma slipped into a coma and passed away. She was six years old. Two years later, Hugo passed away at age 10.

After their three children passed, the Cederroths poured all of their time and energy into the Wilhelm Foundation. “We had met so many families in various hospitals who had undiagnosed children,” she says. “We wanted to figure out our own diagnosis, but to do this for those families as well.” They offered support groups for other families and worked with the NIH to get funding to research undiagnosed diseases. By connecting with other people dealing with undiagnosed diseases, the couple began to understand this wasn’t just a problem in Sweden: Families across the globe needed answers.

That’s when the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative stepped in to help. They awarded The Wilhelm Foundation a grant through their Rare As One Project, which provides resources, tools, and funding for patient-led organizations working to eradicate and spread awareness about undiagnosed diseases. “This money has allowed us to connect with specialists all over the world,” Cederroth says proudly. “We’ve been able to bring geneticists from countries like Pakistan and Central Africa to study with top physicians, so they can bring their knowledge back home to their patients.”

The money also helped the organization fund an event last June called the Undiagnosed Hackathon. They invited some of the most brilliant minds in science to a conference, where the scientists met with 13 patients with undiagnosed conditions — 11 of them children. 95 experts from 28 countries arrived for two days in Stockholm, where they examined the patients and took samples of blood RNA to analyze. The hope is that this event can bring some answers to these families, and also to let them know there’s a team of people out there who care.

It’s been over 20 years since the Cederroths started the Wilhelm Foundation, and Helene still doesn’t have a diagnosis for the disease that claimed her three youngest children (their eldest daughter is healthy and never showed symptoms of the condition). Although the NIH has blood samples from the children, there isn’t enough DNA to determine a firm diagnosis. Cederroth is holding out hope that decades after their children’s deaths, they may finally get some answers.

But for now, Cederroth has found some semblance of peace by knowing that her children’s legacies are helping other families and that their short lives were filled with so much joy. “I don't want to remember my children as they died,” she reflects. “I want to remember them as they lived. I will always be grateful for the time we had had with them.”