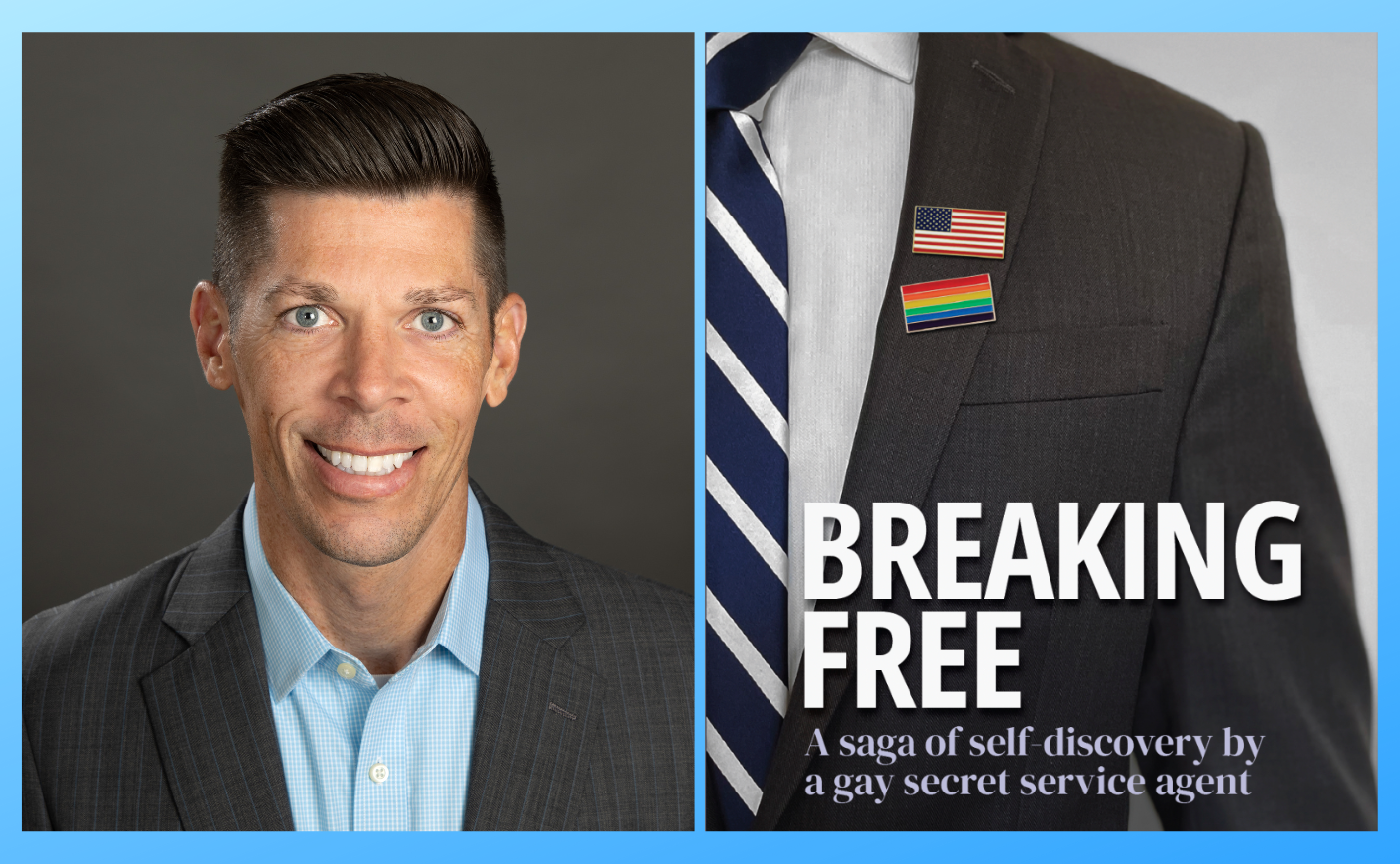

It’s rare for someone who’s made their living as a master of secrecy to write a book as confessional as Cory Allen has, but he pulls zero punches in his memoir Breaking Free: A Saga of Self-Discovery by a Gay Secret Service Agent.

The book is open and honest about entrenched homophobia in the world of law enforcement, which Allen experienced firsthand through his work in the military, a sheriff’s office in Virginia, and then the Secret Service, which he joined in 2010. It also goes deep on the ups and downs of his love life, which was especially complicated because of the pressure to hide his sexual orientation in these traditionally hyper-masculine spaces. But there’s plenty of excitement in Allen’s story, too: He was assigned to Michelle Obama’s security detail in 2016, and he writes about the whirlwind of her post-White House life, including a star-studded trip to the Grammys in 2019. (More on that later.)

We caught up with Allen about the process of coming out, the intensity of life as a Secret Service agent, what it’s like to take a spin class with the first lady, and much more.

You write that you understood your sexuality early on, but you couldn’t be open about it in a professional setting. Did you feel like you were living two separate lives?

That was exactly it for the first 15 years of my law enforcement career. In the military, it was “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” I fell for a classmate of mine, and I had to hide that — I would have been kicked out with dishonorable discharge, which would’ve tanked any kind of government career that I aspired for. The sheriff’s office was heavily Republican, and the sheriff could just fire you. It wasn’t a safe environment. Unfortunately, we have to perfect this ability [to hide our sexuality] to ensure that we survive in our given professions, and mitigate the discrimination and gay-bashing that comes along with working in these environments. It wasn’t until the last five years that I was able to come out and merge my two lives as a law enforcement officer.

What were some examples of the homophobia or hostility you observed among your colleagues?

In policing, my direct supervisor used the F-word in the middle of roll call, which is when we get our briefing before we hit the streets and patrol. The environment was inherently unfriendly. Even once I got into the Secret Service, I was sent to the airport squad, away from the main office and my peers, just to hide me — because the supervisor said they “didn’t want that f--” in the office. I just dealt with it because I had to survive. I could have been fired, but I was supporting myself and my then-husband.

At the time, same-sex couples who were married had been denied insurance, Social Security benefits, and all the stuff that heterosexual couples get when they get married. We’d been paying into the same programs for years, yet we were told we weren’t eligible. In June 2013, when the Supreme Court overturned that, I was the first Secret Service agent to demand benefits for my husband. They were like, “Well, we don’t have a policy for that.” They were waiting on guidance from the Office of Personnel Management to dictate how to make these changes, because I guess they didn’t see this coming? I don’t quite believe that.

You write that the hiring process for the Secret Service was very intense, including a lie detector test that left you feeling like "a total dirtbag" even though you had an incredibly clean record. What was that like?

It was a nerve-wracking time. I applied in August 2008, and I didn’t finish the hiring process until December 2009. They’re interviewing your family, your friends, and your neighbors. They’re doing home visits. They did interview my then-partner, and I didn’t know if they realized we were in a relationship. I assumed so, but I wasn’t going to say it.

The six-hour polygraph was awful — they spin things to get you to admit things you otherwise wouldn’t. It came out that I was gay because they asked if I’d done anything in my life that my family would be ashamed of. I’d just come out to my mom and was trying to reconcile all the emotions wrapped up in that. I didn’t want to fail the polygraph — if you come across as being deceitful, then you’re done — so I had to tell my polygrapher that my family was probably ashamed that I had come out.

I was under the impression that this information would stay at the headquarters level, but there are no secrets in the Secret Service. I didn’t find out until later that headquarters had called down to Miami and told the big boss there that I was gay. I arrived with this machismo “front,” if you will — just my normal law enforcement self — and the whole time, they knew that I was gay, which led to me being discriminated against.

How would you describe the relationship between a Secret Service agent and the official they’re protecting?

It’s professional at all times. I was with the Obamas for about three years, going on the road for book tours and post-presidency travel all over the globe. I was assigned to Michelle, and she knew me by first name — I was spending a lot of time with her on drives or flights, in close environments. The Obamas were very cordial and very authentic. They would ask, “How are you? How are things?” But it was always professional — what was going on at home and in my relationships, none of that came up. It was irrelevant to my work, at the end of the day.

You were assigned to the Obamas’ detail in November 2016, as they prepared to transition into post-presidency life when Donald Trump took office. What was it like being with them during such a fraught time politically?

I was witnessing history in the making. One night, I was the lead agent at Trump’s inaugural ball at Union Station, and the next morning I was at Joint Base Andrews, where Marine One came from the Capitol, with President Obama and Michelle on it. They got on Air Force One to take off for the last time, heading to California.

It was surreal to witness all of this — and the anxiety that the nation was feeling — and I was looking for hints about how they were reacting to this situation. That’s not something I would ever speak about, because they deserve their privacy. But having a role in that transition, of ensuring the safety of both the incoming and outgoing president, was a unique experience.

Michelle Obama is one of the most beloved first ladies in recent history, and you had a proximity to her that most Americans will never experience. What can you say about what she’s like as a person?

She’s bubbly and genuine. [She and Barack] both remained grounded coming out of office and into huge successes post-presidency. I left in 2019, but their personalities never changed. Being with Michelle on the Becoming book tour, I saw how she was able to connect with people as she was selling out stadiums across the globe. The power of her story, the way she tells it, and the way she can just be herself certainly inspired me. I wanted to write my book first and foremost for myself, to process everything I’ve been through, but I thought it would be amazing if I could make just a fraction of the impact she’s had.

One of your Instagram captions says, “Fitness was a requirement with Michelle O!” Tell me more about that.

It was absolutely a prerequisite. She is so into fitness, and I also love it, so that was phenomenal for me: We did 14-mile hikes through the Malibu hills and took spinning classes. I’d be behind her in a packed SoulCycle class, sweating it out with my gear on. I had to remain in top-notch condition. If we’re on the slopes in Aspen, you can’t let the first lady pass you. I was getting paid to not only be around the first lady, but also to work out. It was fantastic.

Your final trip with Michelle before moving on from the Secret Service was accompanying her to the Grammys in 2019. What was the energy like around her in a room full of superstars?

I hate to keep saying “surreal,” but I don’t know what other word to use. She walked onto the stage with an incredible group [including Lady Gaga, Jada Pinkett Smith, and Jennifer Lopez], but she got the most applause of anybody. I got actual goosebumps when she walked out and the place erupted. We were witnessing an amazing first lady who had become an A-list celebrity, and she built all this herself. To be backstage and see all these music icons — from Dolly Parton to BTS to Ricky Martin — it’s surreal to be in that environment.

I also got to meet Beyoncé and Jay-Z in Paris and go to their concert, which was amazing. But that’s a double-edged sword — I got caught up in the glam and the allure of that spotlight, but it was never on me. I was aware of that, but it’s still so entrancing. As I stepped away from the job, it was like, “Well, that wasn’t actually my life.” But while I was living it, the things that meant the most to me were flying by at breakneck speed.

Would you say leaving the job was a comedown, emotionally?

It was a retooling and a lot of reflection, which flows through the book because as I was processing everything, I was writing. There’s a lot of vulnerability in the book, whether it’s talking about my failed marriage or being married to my job. I’ve reflected and spoken to a therapist, and I’m making sure I don’t repeat my past mistakes going forward. What we do is important, but we have to take care of ourselves and those at home.

How would you describe the work you’re doing now?

I’m still in federal law enforcement, and I supervise agents in San Francisco and Seattle who investigate fraud, waste, and abuse in the federal government. I’ve got six years until I retire.

Some of the agents you oversee now are members of the LGBTQ community themselves. How has the attitude toward gay agents changed since you started?

It varies from team to team. Of course, I welcome them with open arms — I want that diversity as much as possible — but unfortunately, I do get messages from agents and officers thanking me for telling my story and saying they can relate. One agent told me he Googles himself every morning to see if he’s been outed. I would love to create a national organization for LGBTQ law enforcement or work with existing groups to fill that void. The environment is not 100 percent better. But by continuing to talk about it and be vulnerable, my hope is that we can generate the change we need.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.