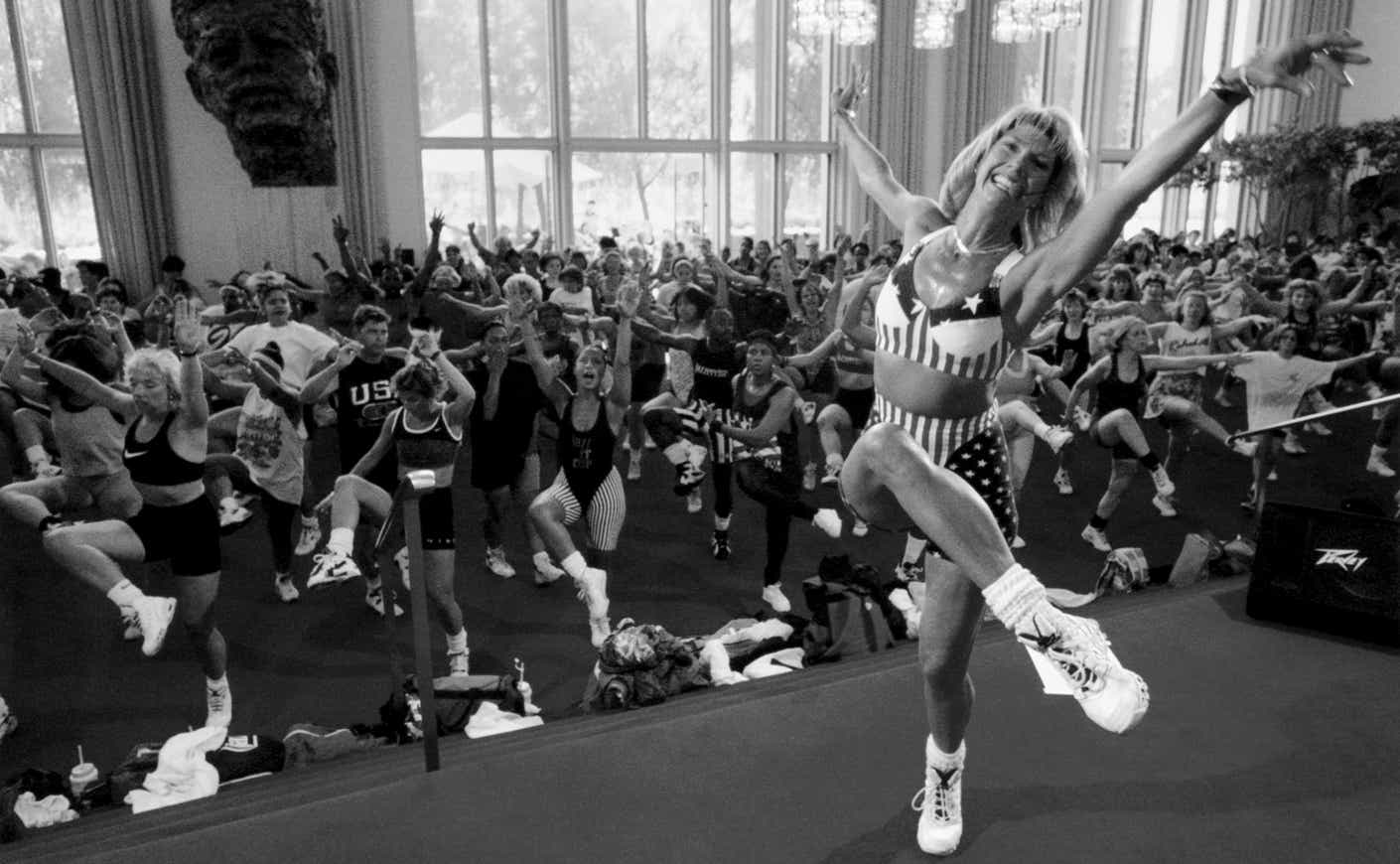

Judi Sheppard Missett is, at 79, still dancing. But these days, she’s traded in her fuschia 80’s-era leotards and legwarmers for roomier, more modern tanks and leggings. And she’s still blonde — though now her hair’s sleek and frames her face, no longer feathered into bouncy curls, as it was when she created the cultural sensation known to millions as Jazzercise.

The aerobic dance craze hit its heyday in the late 70s and early 80s, as a juggernaut selling hundreds of thousands of books and VHS tapes, and being referenced on shows like Taxi and The Golden Girls. Since then, Jazzercise has taken on a quirky, retro patina: In this age of hyper-macho Crossfit routines and stern, laser-focused pilates regimens, the idea of “moving your boogie body” might seem a little silly. But what Judi’s telling me now from her home outside San Diego is that during the 50-plus years she’s sustained her business, she’s changed with the times — and Jazzercise has, too.

“The program hasn’t stayed the same,” she says. “The business is not the same. The basics are there, but you know you have to change with the times.”

Judi knows that in the popular imagination, she and Jazzercise remain frozen in time — trapped in 80s amber, forever hip-thrusting in body-hugging lycra. She’s also aware that many Americans might not even know the company’s “still here,” she tells me, or if it’s faded from view along with Tae Bo or the Thighmaster. But she assures me that today, there are more than 8,000 Jazzercise franchisees operating in 32 countries; last year it drew in $74 million in revenue. And Judi’s just as exuberant about her once immensely popular aerobic dance brand as ever, though she’s handed the reins of the company over to her daughter.

Of course, the world of women’s fitness is a lot more crowded than it once was, thanks in part to Jazzercise’s success. It’s spawned countless dance-based workouts, from Zumba to Sculpt Society, and now competes with the likes of yoga, Peloton, and a long list of others. But with its reputation as a pop-culture relic, could Jazzercise transform itself enough to slide back into the mainstream and seduce a younger clientele? I posed the question to Judi and her daughter, Shanna Missett Nelson, who last year became the company’s CEO.

They countered that Jazzercise has never really stopped changing, not since Judi taught her first class in a small studio in Chicago more than 50 years ago. The program that we’ve come to know, the one that’s been meme-ified and skewered on SNL, no longer exists and hasn’t for a long time, Shanna tells me. The brand has never been afraid to modify its workouts to reflect new fitness trends or the shifting ways women have come to think about exercise and the purpose it should serve.

“We’ve always evolved and changed. That’s part of our secret sauce,” Shanna says. “But we’ve always stayed true to our fundamentals, which is dance fitness.”

Building a Dance Empire

Jazzercise was born in 1969 when Judi, a new graduate from Northwestern, began teaching a jazz dance class for adults. Her students were mostly mothers whose daughters were already taking lessons and decided to give it a try themselves. But after a few weeks, most of them had quit.

“It bugged me,” she recalls. “So I thought, I’ve got to find out what’s going on here.” She tracked down the young mothers, who told her that the choreography was just too complex and that the lessons weren’t fun. What they wanted, they told her, was not to be a professional dancer — just to “look like one.”

“That was kind of the aha moment,” Judi says. She revamped the lesson, keeping the moves simple and repetitive, coordinated her routines to pop music, and turned her students’ attention away from the mirror and onto her. All they had to do was follow her lead while she lavished them with positive encouragement. The revised classes were an instant hit.

This early pivot is a prime example of Judi’s willingness to experiment and her company’s resilience, says Danielle Friedman, author of Let’s Get Physical: How Women Discovered Exercise and Reshaped the World. “From its earliest days, Judi and Jazzercise have really been masters in reinvention,” she says. “It’s built into the company’s DNA.”

By 1982, Friedman writes, Jazzercise had more than a thousand instructors spread across the world, becoming the second fastest growing franchise in the country behind Domino’s Pizza.

When Jazzercise Met Feminism

For so long, women were made to believe that “the most important thing about a female body is not what it does but how it looks,” Gloria Steinem writes in her book Moving Beyond Words. “The power lies not within us but in the gaze of the observer.”

Steinem and other prominent feminists came to see exercise as a radical path to empowerment — despite its connection to weight loss Jazzercise emerged during this culture shift, Friedman says, when the myth that a tough workout could literally cause a woman’s uterus to fall out, was only just coming to be seen as patently ridiculous. Part of Jazzercise’s success, she says, is that it allowed women to enjoy movement, and to sweat freely, under the guise of dance — a traditionally feminine discipline.

“There was still a lot of stigma around pursuing strength for strength’s sake,” Friedman says. But dance was “nonthreatening,” something any suburban housewife could do on a weekly basis without being considered “subversive.” It had another draw, too: Judi understood that despite the feminist vision of exercise as a form of asserting physical power, the average young mother still cared deeply about maintaining her tiny waist or slimming her thighs. And Judi was willing to position Jazzercise as a means to transform hordes of American women into, if not dancers, someone who at least looked like they belonged on Broadway — to, as she puts it, “give the people what they want.”

Since then, there’s been something of a critical reappraisal of female fitness trends and the fact that the early pioneers — like Judi or Jane Fonda — who championed them were “uniformly thin, usually white, and possessed a particular body type, of long, lean muscle,” Friedman says. Today, much of the fitness-related messaging of the 70s, 80s, and 90s — in which women were encouraged to tone and target their problem areas, and melt away extra pounds — would be considered fatphobic.

As more women began to reject this imperative of thinness and came to embrace fitness more for its psychological and health benefits, Jazzercise has been forced to recalibrate. Its stance was tested in the early 2000s, when Jennifer Portnick, a plus-sized fitness instructor, filed a discrimination complaint against the company for blocking her from becoming a franchisee. In a letter, the company told her she was unfit, because “a Jazzercise applicant must have a high muscle-to-fat ratio and look leaner than the public.”

Portnick shot back that she regularly exercised and was perfectly healthy, but simply didn’t have this idealized physique. Ultimately, Jazzercise conceded, adopting a size-inclusive policy, which is apparent in its marketing today.

Like most of its competitors, Jazzercise has made a “wellness” pivot — framing its workouts as a “self-care” activity. Its programs now include strength-training segments involving handheld weights, as more women look to build muscle and not just slim down. It also has a streaming home workout program, Jazzercise On Demand, which it fortuitously launched ahead of the pandemic. And in its quest to modernize, it’s brought in a third generation: Judi’s granddaughter, Skyla Nelson, who’s piloted a new workout focused on high-intensity interval training.

Skyla, at 20, is eager to jump into the family business and believes that anyone, even Gen Z, can get “hooked on” Jazzercise. I wasn’t so sure. It’s hard to imagine that a younger set wouldn’t be repulsed by the memory of their mothers shimmying in spandex, despite Shanna’s insistence that although they do “skew a little bit older,” Millennial Jazzercisers do exist. So I set off to experience a class myself.

What Does Jazzercise Look Like in 2023?

On a Wednesday evening, I pulled on a moisture-wicking tee and leggings and headed down to a small studio in Manhattan’s Financial District to attend one of two Jazzercise classes offered nearly everyday in New York City. I arrived early and waited in the lobby, listening to another instructor tell her class to “step” and “kick” over a dance remix, alongside Erica, a 35-year-old attending her fifth Jazzercise session. She found the program via ClassPass, a subscription service that gives users access to a panoply of fitness offerings for a fixed monthly fee. Having already tried Soulcycle, she got curious about Jazzercise because of its “low intensity” routines.

“I was expecting jazz hands,” she tells me. “But it was actually a really fun workout.”

There were only three of us in attendance: Me, Erica, and another woman in her 30s (who I was informed is a “regular”). We were led into the studio by Alexandra Lance, a 27-year-old from Houston wearing a Jazzercise-branded sports bra and matching leggings. She promptly began playing Beyoncé’s “Summer Renaissance” and instructed us to roll our hips as we strutted forward and back. At this moment, two things sprung to mind: That I have absolutely zero dance experience aside from being forced to learn The Hustle in high school gym class; and that I’m rhythmically bankrupt. I prefer to do my dancing at least one drink in, in poorly lit bars where I’m certain I won’t be scrutinized.

Lance, who’s been Jazzercising ever since she was a kid at her mother’s studio in Humble, Texas, relayed instructions to “reach” and “twist” and “move those hips” through her headset. The other two women much more deftly managed the routines, while I remained focused on Lance as she spun and mamboed to Pitbull, trying to mirror her and mostly failing. But emboldened by Lance’s steady stream of encouragement and effortless enthusiasm, I awkwardly pressed on, and eventually found my groove. Or, at least came to care less about “step, twisting” instead of “step, step, twisting” and just savored moving with the music.

After about a half-hour, we grabbed 4-pound weights and did sets of squats and arm raises timed to the pulsing bass of a J Balvin song, closing the session with light stretching. (There were no jazz hands.) By that point, my thighs and shoulders burned, I was covered in a fine layer of sweat, and I’d discovered what thousands of other Jazzercisers already knew — that exercise is better with a beat.

When I spoke with Erica after the class, she told me that if not yet a full convert, she’d definitely be coming back for more: “It just helps me embrace the joy of movement.”

That sounded familiar. From the start, Judi has said that Jazzercise, at its core, is about getting to know your body and discovering the pleasure of moving unselfconsciously. “Be good to yourself by learning to become free and uninhibited in your movements!” she writes in her 1978 book, Jazzercise: Rhythmic Jazz Dance Exercise, A Fun Way to Fitness.

It’s this element of the brand that may help it endure, Friedman says: “There’s something of a renewed interest in retro fitness,” she says. “I’ve gotten the sense that people have found some of these older workouts a little more liberating. There’s a sense of playfulness to them that’s sometimes lacking in the more hardcore workouts today.”

Though Jazzercise may never be the oft-referenced cultural phenomenon it once was, the primal joy of moving to a beat — sans complex equipment or the pain that's celebrated in more aggressive regimens — is admittedly irresistible in its simplicity. And from Judi’s perspective, the brand is almost guaranteed to have staying power. Now, more than 50 years in, she’s certain that Jazzercise will be around “long after I’m gone.”