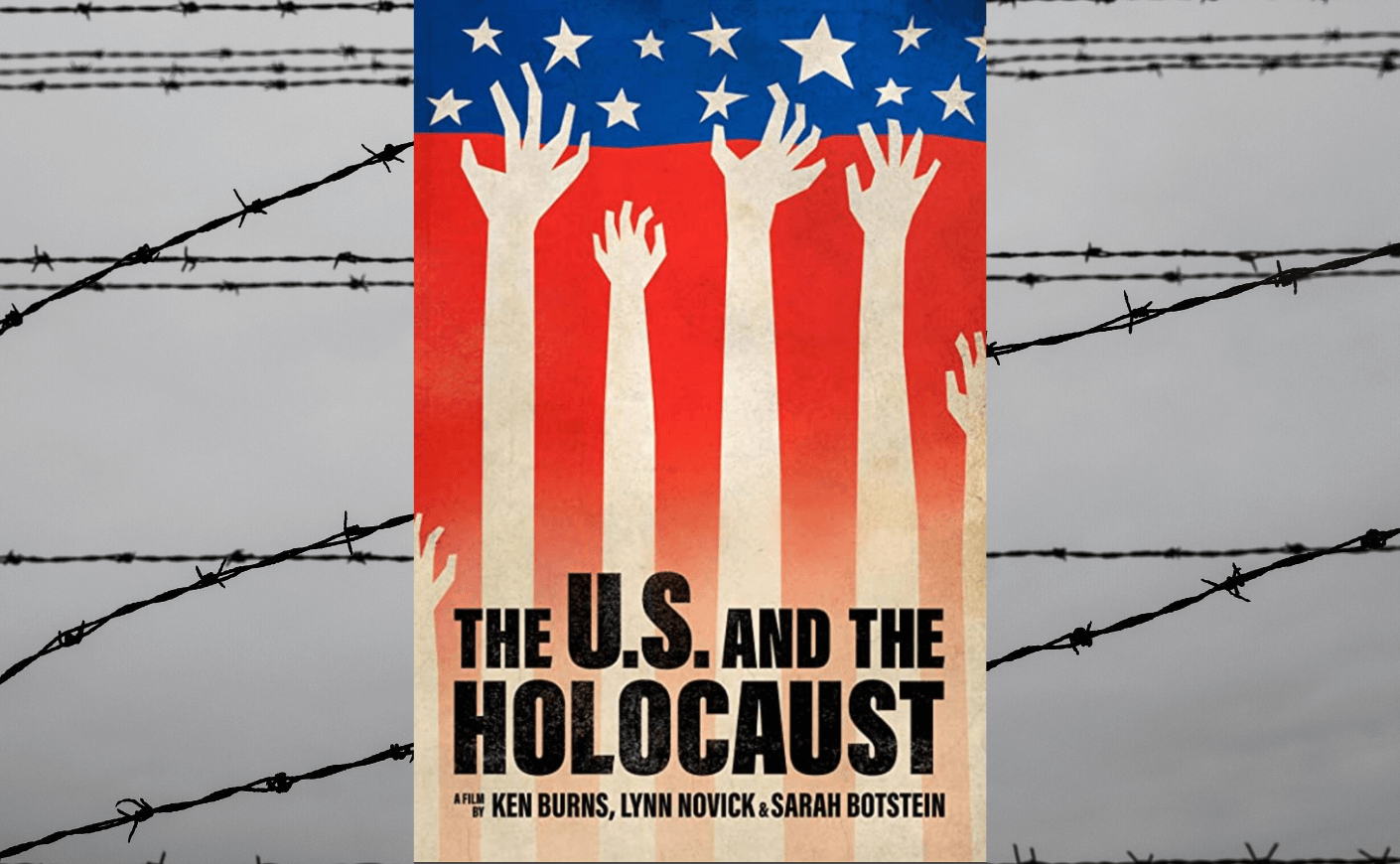

As many of you may have read, I was incredibly moved by the six-hour PBS series entitled The U.S. and the Holocaust. I was honored to have a conversation with Lynn Novick, one of the creative forces behind the series. We talked about the factors that contributed to the genocide that took place less than a century ago — from institutions like the State Department that suppressed critically important information to immigration policies that set the stage for closing our borders to desperate Jews trying to flee the Nazis. I can’t emphasize how important this documentary is. Here's my and Lynn's lightly edited conversation.

Lynn, I was blown away by this series: I thought it was extraordinarily powerful, heartbreaking, and educational. But when I first started watching, I wondered what you would be covering, since there have already been so many documentaries about the Holocaust. What did you want to explore that hadn't been explored before?

Thank you for framing the question that way. I'll speak for myself, but I'm also going to try as best I can to represent the collective effort that is myself, Ken Burns, and Sarah Botstein — who made the film together — and our writer Geoff Ward, who wrote such a beautiful script. When we embarked on this project, I was driven to find out the answers to some questions that I really did not know myself. I was very aware that there's been a lot of media made about the Holocaust: I've seen dozens of documentaries, read books, watched feature films. So we certainly had to think to ourselves, What can we say that hasn't been said?

When we thought about the perspective of America, and the American response to this catastrophe, that's where we felt we could shed some new light, at least for the general audience. So it was about trying to find out what the American people knew about what was happening in Europe. How did we know it? When did we know it? What did we believe? And when I say “we,” I'm talking about the ordinary American, the Jewish community, the leaders in Washington, and the press.

I've always wondered the answer to those questions too, Lynn. Why didn't the U.S. do more about the killing of Jews in Europe? Why didn't they act sooner and more forcefully? Jews were being killed, gas chambers were being constructed, and yet nothing was really being done. I think one of the first factors was immigration policies that were established in the 1920s, that in some ways set the stage for the nativism and the isolationist tendencies that became so deeply entrenched in the years leading up to World War II. Can you talk about that?

Yes, absolutely — that's the critical question. When we began the film, we didn't begin when the Holocaust began. We didn't begin even when Hitler came to power in 1933. We had to go back to understand why it was so difficult for refugees to get to the United States. We think of ourselves as a nation of immigrants, and we have the Statue of Liberty, and the beautiful poem... And yet when people were most desperately in need of a place to find a haven, America's door was not open. My ancestors mostly came here before 1924, so, working on this project, I had to think, Wait, when did my relatives come here? They came from many of the places where the killings happened, and if they hadn't come when they did, they all would've been killed.

To answer your question, in 1924, Congress passed a law called the Johnson-Reed Act, and it changed our immigration policy completely. Before that, the U.S. had an open door, and if you could get here, you were welcome, essentially. After 1924, there was a strict limit on the total number of immigrants, and there were separate quotas for every country. Those quotas were set up with an explicit purpose to kind of re-engineer the American melting pot, so that people who had been coming in large numbers from southern and eastern Europe were no longer welcome here.

And the countries that had sent hundreds of thousands of people to the U.S. could now send tiny fractions of that number. The quota for Poland was about 3,000 people, if I remember correctly. They reserved the most spots for from the northern European countries; the people who made the laws in America thought, Nordic stock, that's what we want — a white, gentile nation. There were changes happening from the late 19th century, with waves of immigrants coming from places that they considered inferior. So it was kind of trying to re-engineer America by cutting off the flow of immigrants.

Those policies were racist and anti-Semitic.

Correct — they very carefully created the legislation that way, but it was never said explicitly, “We're trying to keep Jews out.” But the places they were limiting immigration from had the largest populations of Jews. They also limited the number of southern Europeans, Greeks, Italians… Any immigrants the white Anglo-Saxon Protestant elites of this country felt shouldn't be welcome here. They used words like “we're heading toward a ‘racial abyss’ if we let this immigration continue.” That law wasn't adjusted or repealed until 1965, so that system remained in place for 40 years, and it was very popular. It’s a bitter pill to swallow, looking back, because it seems not representative of our better selves — what America could be. But there was never a successful effort to revise or repeal the policy, until the Johnson administration.

Right, when LBJ made that announcement in the shadow of the Statue of Liberty.

Yes, exactly. He said they were trying to redo the wrongs of the past, to make America live up to its promise of having our “golden door” be open again. Look, I think it's fair to say that in 1924, there was no spectre of Hitler or the Holocaust. The immigration law wasn’t put in place to stop refugees from getting here who would otherwise be killed. But as the news in the 1930s began to trickle out about how oppressive the Nazis were, and how impossibly dangerous it was for the Jewish populations who were under their control — even after Kristallnacht, which was a public attack on Jewish society and Jewish people — the American public saw the news and said, “That's terrible, but we shouldn't change our immigration policy.”

One of the many chilling things that the documentary reveals is that Hitler actually got some of his ideas from America. When it came to extermination of the Jews, he looked at Native American genocide, and the oppression of Black people in this country. That was startling to me.

It's pretty shocking — that was news to me as well. Before we worked on the project, I hadn’t heard that in his career, developing his ideology, Hitler looked to America as an example. He most admired the way that we had either subjugated or exterminated our native populations as we had moved west across the continent. And he envisioned Germany moving east across Eastern Europe and doing the same thing to the people there. And he also thought that the model for how we had created a caste system, and basically put white people at the top and Black people at the bottom, was admirable.

When he came to power a few years later, he sent his lawyers to the United States to study our Jim Crow laws. What kind of laws do you need? How do you define, for example, who was a Jew or who was a Black person? What are the rules? How do you start to strip away what people can and can't do, whether they can be married, whether they can have certain jobs. The infrastructure that we had created under the Jim Crow system, the Nazis were emulating. Isabel Wilkerson wrote about this in her extraordinary book, Caste, and there's a professor at Yale Law School, James Whitman, who wrote a whole book about this. We're not responsible for the Holocaust — we're always very clear about that. Hitler took these ideas to a grotesque extreme. But the ideology behind a type of racial-purification project, we have some responsibility for that.

You write a lot about FDR, who was obviously president during this time period. One of the things I appreciated is that you’re sympathetic to the political bind he found himself in, but also critical of his lack of action.

Yeah, we tried to present the whole context for what the president was dealing with in this isolationist, anti-Semitic, racist country. You know, remember that before the U.S. gets into the war, Charles Lindbergh is one of the most popular people in America, and he's spewing anti-Semitic and overtly racist stuff in his speeches. He's getting huge audiences, and it's a serious political threat to Roosevelt. So that's just one small dimension of the larger context — that there's political realities that FDR has to deal with, of trying to get the country prepared to actually be involved in a war against Hitler. And many of the scholars we talked to asked if Roosevelt had gone on the radio and said, “This is a war to save the Jewish people of Europe,” what are the chances that Americans would've said, “Great, count us in”?

There was a period of time, in the sixties and seventies, where anti-Semitism did seem to have really dissipated. And now we're seeing it coming back with a vengeance. But it's always there in one way or another, and Roosevelt was acutely aware of that.

You know, this was not the finest hour for the Fourth Estate: I was stunned and ashamed in retrospect on behalf of journalists in this country, because it took a very, very long time to report this news. Even when journalists witnessed events firsthand, they cast doubt on what they saw. And as a result, people didn’t take what was happening seriously enough.

I agree with you. I wish that that had not happened, but I also have some compassion, in the sense that they were witnessing something unprecedented and somewhat unimaginable, even as it was happening. There was this history of war propaganda during World War I — some skepticism and mistrust, especially when it came to Soviet sources. But I do think there's so much more that could have been done, in terms of the words that were chosen. The other thing to say is that until early in ’45, when the first sites of mass killings were discovered, there were no photos — just words on a page. It was easier for a reporter or an editor to say, “Hmm, we'll put kind of a ‘maybe’ around this whole thing.”

Well, that might be true of the concentration camps, but when it came to taking material possessions from Jewish families, sticking them into ghettos, making them wear yellow stars, sending them to labor camps… I mean, all of these horrific things preceded the actual construction and use of gas chambers. There were so many warning signs, and journalists had access to that information.

I can't disagree, you're absolutely right. And is it because those lives weren't valued, or because the people who were editing the newspapers just didn't think this was a big story? I wish I could have been in those editorial meetings, because there were journalists like Dorothy Thompson, who's such an amazing figure, and others who really tried to sound the alarm. But those voices weren't loudest.

I'd like to read an excerpt from The Nation, which had one of the most beautifully and harrowingly written accounts, by someone named Freda Kirchwey:

“In this country, you and I and the president and the Congress and the State Department are accessories to the crime and share Hitler's guilt. If we had behaved like humane and generous people, instead of complacent, cowardly ones, the Jews lying today in the earth of Poland and Hitler's other crowded graveyards would be alive and safe. And other millions, yet to die, would have found sanctuary. We had it in our power to rescue these doomed people, and we did not lift a hand to do it. Or perhaps it would be fair to say that we lifted just one cautious hand encased in a tight-fitting glove of quotas and visas and affidavits, and a thick layer of prejudice.” I thought that was so profound.

Yes, and that was written during the war.

Getting back to Charles Lindbergh, I had always heard he was an anti-Semite, but I didn't realize what a Nazi sympathizer he was. Were you surprised by the level of coziness between Lindbergh and the Nazis?

I heard he was anti-Semitic, but when we were putting the film together, I remember asking our team, “Can you just look up some of these speeches again?” I knew the famous speech in Des Moines, which was his last public utterance that was overtly anti-Semitic. He kind of tamped it down after that. But for two years before that, he was out there. We pulled in a bunch of these speeches and you hear him say things like, “Unless the white race is seriously threatened, this is not our problem,” basically. He doesn't want to fight Germany unless Germany, France, and England are all threatened by some non-white enemy. He really admired Hitler as well. I think it's good to have a full 360-degree view of who he really was, what he believed in, and why he was so popular. He wasn't hiding any of this. I think that's the biggest takeaway for me. He was popular partly because he flew the plane across the Atlantic, and that was a very brave thing to do. But he remained popular because he was in touch with something that the American people wanted to hear. It’s pretty disturbing.

And when Lindbergh was organizing his “America first”-style campaign against involvement, I was surprised to hear names like Lillian Gish and Alice Roosevelt Longworth alongside his, in support. I had always heard that Henry Ford was a big anti-Semite, but not them. What the hell, Lynn?

I think this shows anti-Semitism was a very mainstream idea back then. After World War I, it was a potent idea to say we should stay out of European affairs. But given that everybody knew what was going on in Europe, that falls a little flat. I think there's a thought exercise here: We didn't of our own volition get involved in World War II as combatants — we were attacked by the Japanese at Pearl Harbor, and then Hitler declared war on us. And if those two things hadn't happened, it's an interesting question of whether America would've actually gotten involved at all.

My late husband’s father, who fought in World War II, told me many years ago he didn't think that U.S. planes were capable of reaching the camps without refueling and that was one of the challenges.

That's right — until late in the war, the U.S. didn't have the technical capacity to bomb Auschwitz. That's true.

That leads to my next question: What could the U.S. have done that we didn't do? For example, could we have assassinated Hitler? What could have been done now, in hindsight, that would've saved so many lives?

We could have done more, practically speaking, to save lives before 1939. Now, of course, Hitler had not implemented what became known as the Holocaust until after that. But before 1939, that's when hundreds of thousands of refugees were still trying to get here. And if we had just said, “Everybody come on in,” hundreds of thousands — perhaps millions — of people would never have been under Hitler's control, or killed by the Nazis once the war started. We weren’t actually combatants right away — there were two or three years of war before we even got involved. America didn’t have boots on the ground in Northern Europe until D-Day, and by then, three quarters of the people that Hitler's going to kill have already been killed.

The timeline is such that there's not that much, on a military basis, that we could have done to prevent the killing in a significant way. We could have tried to help refugees get here before it started, but we didn't know what was going to happen. So it's a very thorny problem. There's a big debate to this day about whether we should have bombed Auschwitz, once we had the capacity to do that. And there's a debate in the film, which I won't fully spoil for your readers, that shows how tricky that issue was.

Essentially, because bombing wasn't accurate, you might kill more people than you were trying to save. On the other hand, they probably could have found another way, and could have sent a message. Although I'm not a big proponent of sending a message by bombing. But those are real arguments and they're worth discussing, because there's no easy answers.

I think we can't have this conversation without closing on the eerie similarities between what was happening then, and the recent state of affairs in our country, particularly during the Trump administration. I don't think it's any coincidence that “America First” was one of the mottos and policies of the Trump campaign, and the Muslim ban happened during the Trump administration, and there was the march in Charlottesville, where young men were walking down with torches, saying “Jews will not replace us.” I'm curious if the echoes of Nazi Germany in the present day became more pronounced for you all, as you worked on this series.

Absolutely. I mean, we started thinking about this project in 2015, when we were approached by the Holocaust Museum in Washington, because they were doing an exhibition about America and the Holocaust. And we said, “We'd love to do a film about that.” But as the Trump administration came to power, and then we saw what was happening right up through January 6th, it was surreal and very unnerving, and eye-opening. I kept on trying to make sense of what I was seeing. How does this relate to the story that we're telling? People have helped me understand the warning signs of authoritarianism. And when I rattle off these warning signs, you can see them in Germany in the 30s, and many of them you can see now. Like a threat to free and fair elections, the rule of law, the peaceful transfer of power, independent media, and freedom of religion. And a sense of creating a scapegoat, or an “other” who's the cause of all the problems. Resentment and anger towards that scapegoat — obviously in Nazi Germany, that was the Jews. Then there’s the sense that the leader is the state. There’s this kind of conflation, so that if you were to criticize the thin-skinned leader, you're criticizing the nation, and vice versa.

It all does make you wonder: Could this happen again?

I personally don't see the genocide of Jews, particularly in America, happening today. I'm more concerned broadly about the fragility of our democracy, and how any nation can slip quickly into something that will bear more similarity to Nazi Germany than to the United States of 10 years ago. And it can happen slowly or quickly, and it could happen here. I think one of the dangers of American exceptionalism is to feel that we're special, and that terrible things that happen in other places can't happen here. Or that we somehow are immune from these forces. That's a fantasy that we should disabuse ourselves of.