Though Pride Month is known as a time to wave your rainbow flags high and love loudly and proudly, its origins are much darker than the celebrations we see today. The impetus can be connected back to a police raid at the Stonewall Inn, a gay club located in New York City’s Greenwich Village, on June 28, 1969, which led to the LGBTQ+ liberation protests in 1969, known as the Stonewall Uprising.

Activist and photographer Mark Segal remembers these events well because he was there. Segal, who was just 18 years old at the time, says the uprising began on what seemed like an ordinary night: It was the summer of 1969, and he decided to go along with his friends to the Stonewall Inn, which was known as a haven for the LGBTQ+ community to hang out, be themselves, and, of course, dance the night away. Then, police officers poured in, threatening and beating patrons, Segal says — but instead of complying like they normally did when these altercations occurred (unfortunately, this wasn’t a one-off), the crowd decided to fight back.

“It was the most horrific, frightening scene I had ever been part of,” Segal tells Katie Couric Media. “My first reaction in my head was, ‘Oh gee, we better call the police’ — and then I realized these are the police. I felt so low. Realizing that we gay people can be treated like this was probably one of the most depressing times in my life. [It felt like] no one cared about us, not even the police.”

Soon after, Stonewall became a symbol of resistance to homophobia and discrimination. Now, 55 years later, Segal is part of a project to help keep the legacy of these demonstrations alive. On June 28, the Stonewall National Monument Visitor Center will open, marking the first LGBTQ+ visitor center recognized by the National Park Service. “By opening the center, we’re creating more visibility and giving the LGBT people a place to come and be proud,” Segal says.

Here’s a look back at how the Stonewall raid sparked a gay revolution and the importance of preserving this history for future generations.

What happened at the Stonewall Inn?

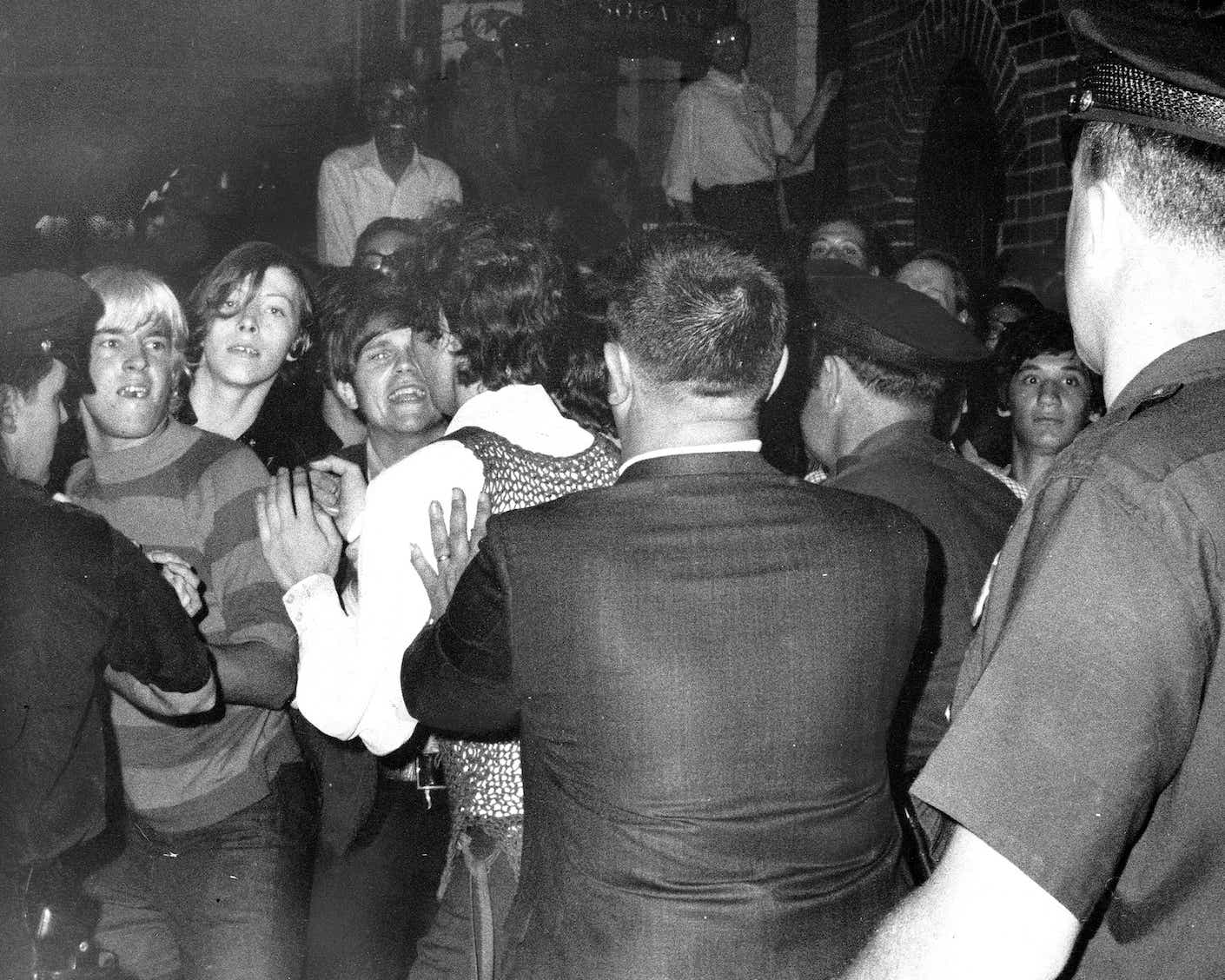

On June 28, the Stonewall Inn was raided by the New York City Police Department, which was all too common back then. Even in liberal cities like New York City, homosexual acts of any kind were still illegal. This meant that bars and restaurants could be shut down for having gay employees or even serving gay patrons. Many of the queer-friendly places, including Stonewall, were operated by the mafia, who paid corrupt police to look the other way, but that didn’t mean these places weren’t a target for regular harassment by the NYPD.

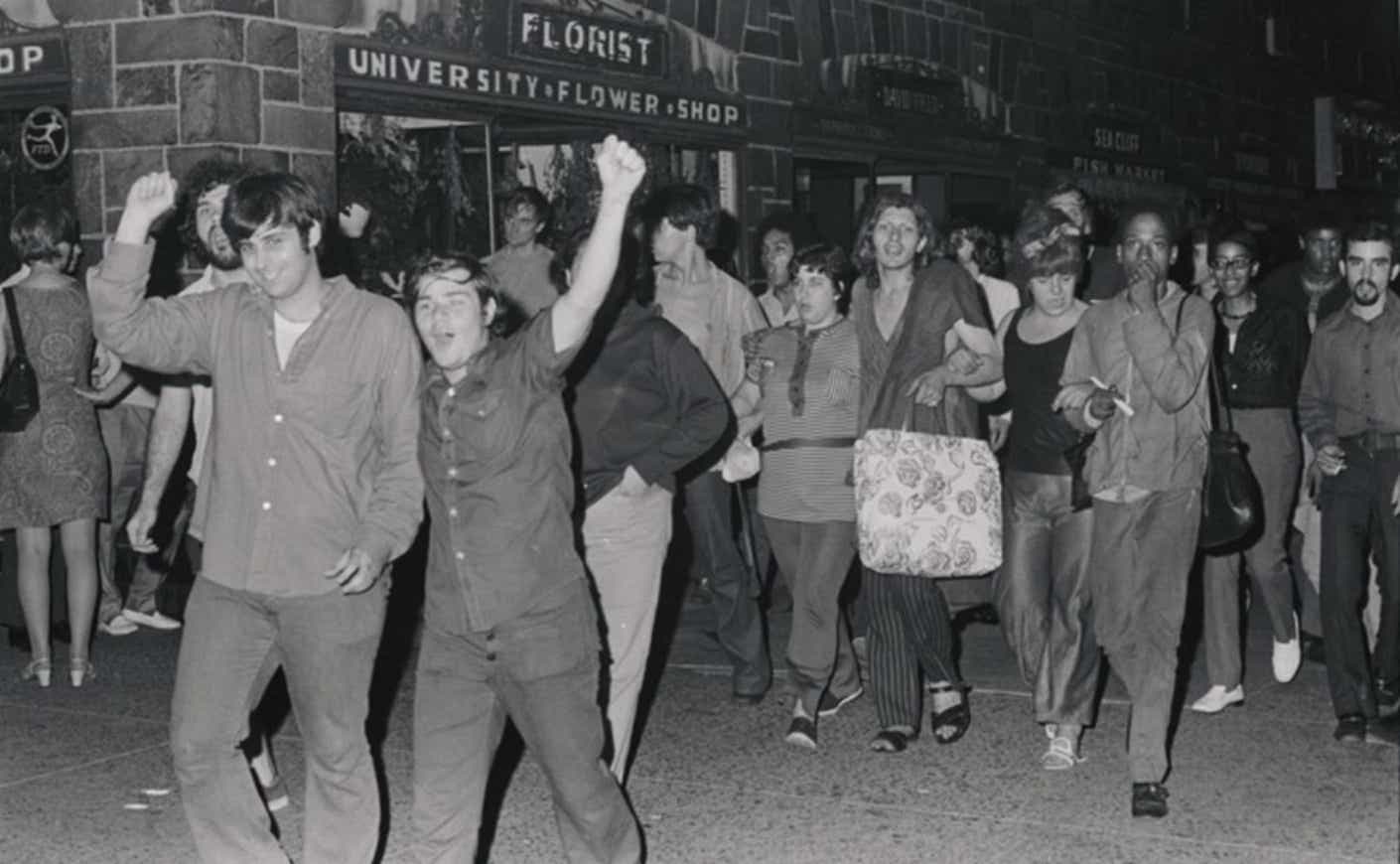

What transgressed the night of the raid depends on who you ask, but according to Segal, officers burst into the bar in the early morning hours while patrons were still carousing. They began arresting the employees for selling alcohol without a license and attempted to take patrons into custody. As they were being escorted away, a crowd of drag queens, street kids, activists, and locals began gathering to defend their own, jostling the police and throwing coins and other debris. Eventually, officers had to call in reinforcements and barricaded themselves inside the bar while people rioted outside.

This tension waxed and waned over the next five days. Law enforcement eventually beat and tear-gassed protestors until they dispersed. But the rebellion forever changed the face of queer life, and the Stonewall Inn became a symbol for the LGBTQ+ movement. It also marked a personal turning point for Segal: “In a sense, it was the day I finally realized who I was,” he said.

These events weren’t an anomaly

LGBTQ+ people faced their fair share of discrimination for their sexual orientation at the time. During the 1960s, homosexuality was classified as a mental disorder. Most cities had laws that forbade same-sex relationships and denied basic rights to anyone even suspected of being gay on the pretexts of religion and morality.

As a result, many were forced to live their lives in secret, with very few resources to learn about their identity available to them other than what their local libraries could provide. However, Segal points out that most books on queer and LGBTQ+ subjects were limited to the criminology, psychological, or religious departments.

“What I discovered was that I was immoral, illegal, and psychologically insane,” he recalls. “That wasn’t very healthy for a young gay boy, but somehow inside me, I knew that was wrong. I couldn’t explain why or how.”

Then late one night, Segal just happened to be watching PBS, depicting gay people living in a popular New York City neighborhood known as Greenwich Village. He decided right then and there that when he graduated high school, he’d leave the only home he’d ever known in Philadelphia and move to the Big Apple. “In Philadelphia, a city of 1.6 million people, I thought I was the only one,” he says. “That’s how invisible we were when I was growing up.”

But upon stepping off the train in New York City, he quickly found community among other queer people. “We could get beat up out on the street,” he recalls. “The police would harass us, but inside Stonewall, it was a safe place.”

The legacy of the Stonewall Uprising

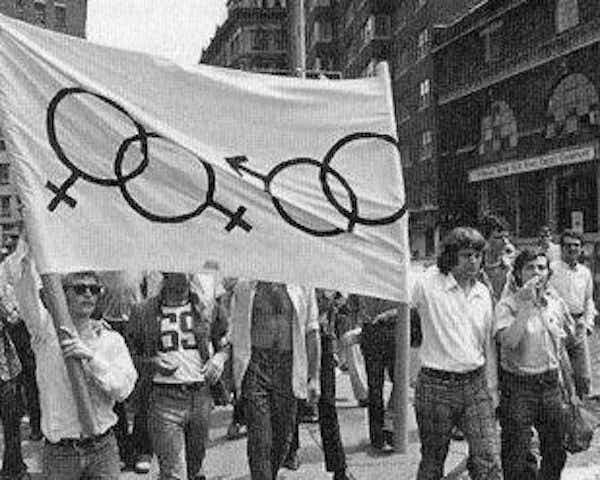

The events at the Stonewall Inn are seen as a revolutionary turning point that stoked the gay rights movement. Soon after, this activism spread to cities across the country.

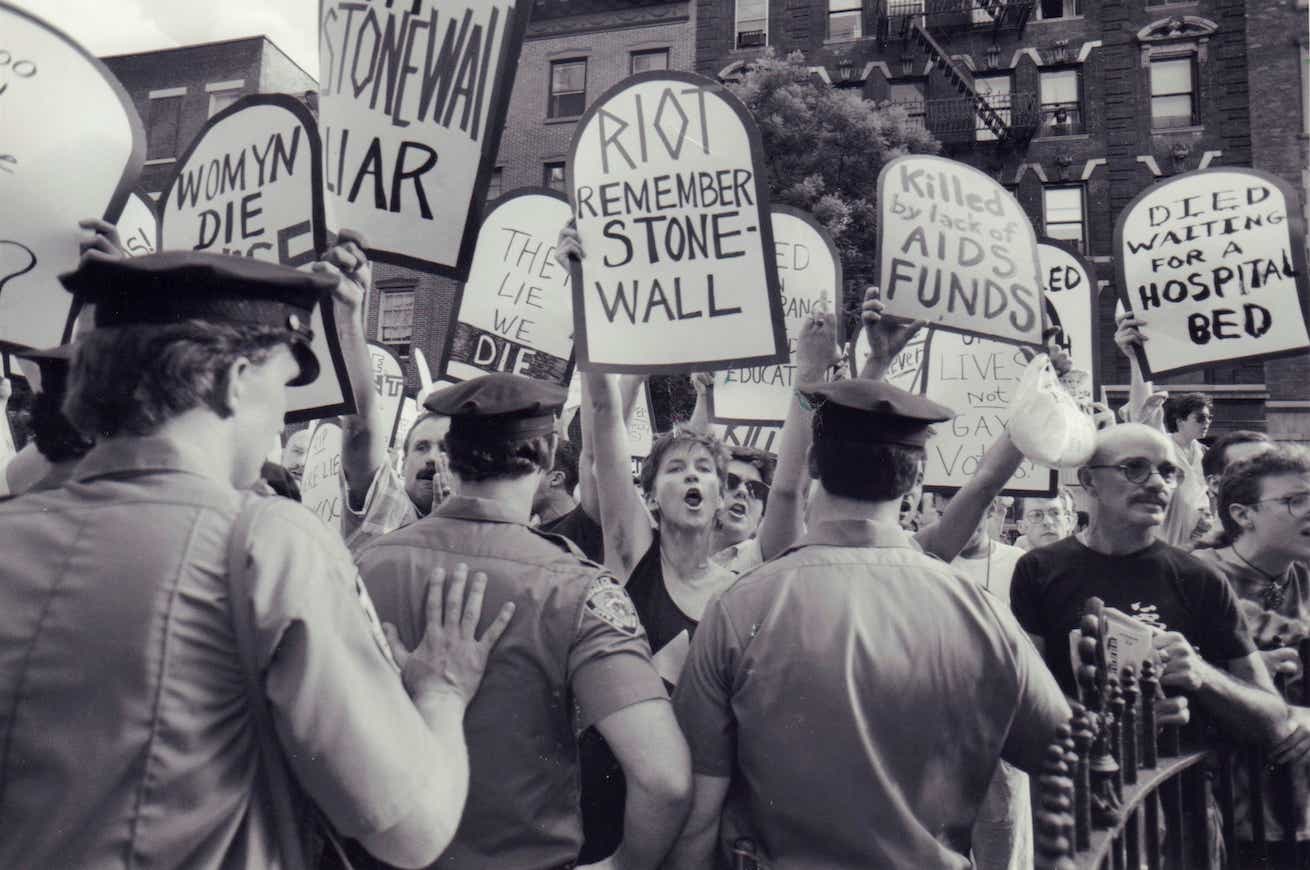

A year after the police raid in 1970, activists commemorated its anniversary with what was the first gay pride march, and the events at Stonewall have been commemorated annually ever since. Then, in 2016, then-President Obama designated 7.7 acres of land, including the original bar and the building next door, the country’s first national monument to LGBTQ+ rights. And now, the Stonewall National Monument Visitor Center is set to open later this month next to the iconic institution to preserve the history of the rebellion. Segal underscores the importance of creating this symbol: “If you don’t have a symbol of your movement or your history, it doesn’t exist.”

The project has been led by Pride Live cofounders Diana Rodriguez and her partner Ann Marie Gothard. They enlisted Segal to be a founding member and help curate the art and pieces featured in the space: “For so many of us, you can read about Stonewall, you can watch a documentary about Stonewall, but with Mark, you can get this history firsthand,” Rodriguez tells us. “That is very rare.”

Rodriguez and Gothard also brought in EDG Architecture + Engineering to design the center. The firm approached the project with the priority of preserving its history and recreating Stonewall’s vibrancy as much as possible. Their efforts included leaving a passageway that connected the two buildings exposed, as a nod to the obstacles the LGBTQ+ community faced and continues to face today. “The passageway provided a discreet entrance to the main bar and dance floor. Patrons entered the space from what is now 51 Christopher Street (the current Stonewall bar), which took you through a corridor and then the passageway to enter the main space. Preserving the passageway was essential because it represented leaving a city that wasn’t accepting and entering a community that was,” Thao Quartuccio-Nguyen, senior architect and graphics coordinator at EDG, and project architect and manager on the Stonewall monument, tells us. “Walking through that passageway was a powerful moment for a lot of people, and for that reason, we left it untouched.” The space also includes a model of the jukebox from the original space and new ceiling panels inspired by artifacts found during construction.

“LGBTQ+ spaces have always dealt with persecution and erasure, so it wasn’t always easy to visualize the details of the bar in the time of Stonewall,” said design director Richard Unterthiner in a statement. “Our design focused on weaving together ephemeral memory and the tangible touchstones found in the space itself in order to honor that history.”

Though the movement has seen many key successes over the past few decades, including the legalization of gay marriage, there’s still an uphill battle for equal rights. At least 510 anti-LGBTQ+ bills were introduced in 2023 alone, which is nearly three times the number of such legislation introduced in 2022. While not all of them have passed, they aim to weaken nondiscrimination laws, limit access to medical care and public accommodations like restrooms for trans people, and ban books and drag shows.

Despite these disheartening attacks, Segal remains hopeful about the future for queer youth: “I can understand young people seeing this as their first backlash and being scared, but I promise them, there’s a light at the end of the tunnel, and if you stay visible, you are the light.”